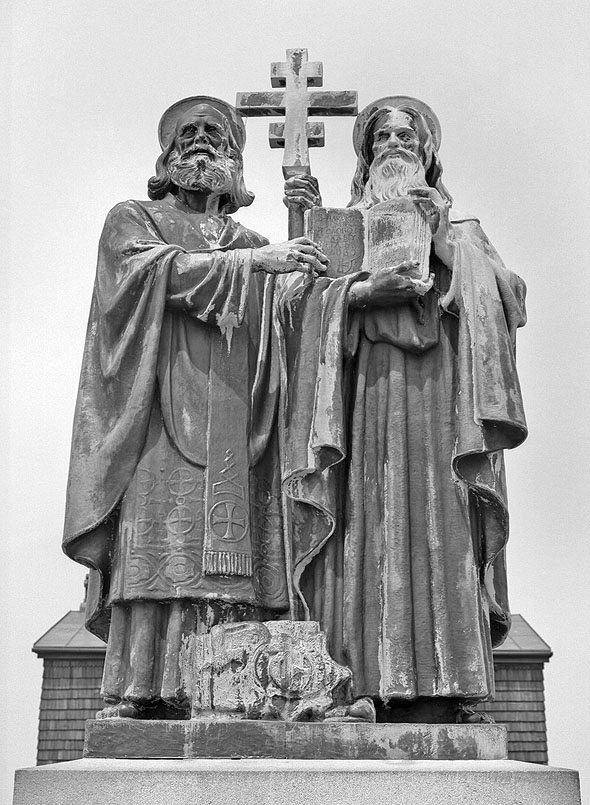

The Thessalonian Saints Cyril and Methodios, Teachers of the Slavs – Part IΙΙ

14 May 2014In Slovenia

The Moravians and Slovenians were waiting impatiently for the brothers, but they did not appear. Kocel of Slovenia sent a letter requesting Methodios and the Pope sent him in the spring of 869, shortly after the death of Cyril.

In a letter to Kocel and Rastislav, he praised the Orthodox outlook of Methodios, ordained that services should be celebrated in Slavonic and characterized as wolves the people who scorned the books written in that language. The Slovenes were extremely unhappy, however, because they had been expecting a bishop and the Pope had been reluctant to consecrate Methodios. He was afraid that Methodios might declare the independence of the Church of Slovenia and Moravia, as he actually did want to do. Kocel acted decisively. He sent Methodios back to Rome with 20 Slovene officials to accompany him and demanded that he be consecrated bishop, making it clear that, otherwise, he would seek his consecration in Byzantium. And the decisiveness of the prince won the day.

The Pope consecrated Methodios bishop and the latter settled in the capital of the Slovene state, with the title of Archbishop of Sirmium, the ancient capital of Illyricum, which was just to the south of the Danube. The ecclesiastical organization created after the activities of the two brothers was autocephalous, as envisaged by Byzantine ideas on the subject. The two great parts of the then united Church differed in this because of tradition and ways of thinking. In the West, the ideal of total concentration and unity, which was inherited from ancient Rome required that, in the Christianized regions, units should be organized as belonging to the one, indivisible Western Church, with Latin as its language and- at that time- under the authority of the German state. In the East, the ideal of a federal association, inherited from Greek and Christian antiquity, contributed to the formation, in Christianized areas, of autocephalous churches, using the local language and under the political authority of independent states.

So this Church was not dependent administratively on either Constantinople or Rome, but would have kept in touch with both. It was founded according to the guidelines of Constantinople and with the Greek spirit of being self-sufficient. Indeed, it was the model for the organization of the other Slavic churches, the difference being that the latter were more fortunate as regards interventions by foreign elements.

Methodios’ activity was all the greater now that he held a more important office. He ordained a host of his disciples, Slovenes, Croats and Serbs, over whom his jurisdiction was extended. The Croats and the Serbs had received the first missionaries from the Byzantine acquisitions on the Adriatic, under the auspices of the government in Byzantium. Christianity now advanced to these in extent and depth.

The three Churches were Slavic in character, but that of the Croats later turned to Rome, under Count Branomir, who, in 879, had murdered Sedesclav. In Slovenia, this character was partially retained until our own time Despite the fact that Roman Catholicism prevailed later. In fact, the first Slavonic script, glagolitic, was preserved there.

At the same period, Methodios also ordained a great many of his disciples from Moravia, whom he sent back to their own country to continue his work. Among these was Gorazd. But this work was brought to an early end. The German ecclesiastical and political leaders were displeased with the results of Methodios’ activity, which gave the Slavic Churches not only Slavonic but also a Greek character, to the great disappointment of the

Latin clergy, and closed the path to another approach to Germany. It was at precisely this time that Louis the German invaded Moravia with three divisions and subjected it again. Rastislav, who had invited the Greek missionaries into his country was dethroned and blinded. Kocel began to fear the same for himself., so when the German clergy in Slovenia arrested Methodios and took him to Germany, he did not react.

In November 870, Methodios was tried by Bavarian bishop in Regensburg, supposedly because he had taken over a region which belonged to the Archdiocese of Salzburg. At that time, there was severe pressure for the Church of Germany to break away from Rome, as we can see in this incident. Methodios called his persecutors “barbarians” in front of Louis.

When he had been found guilty, he was imprisoned at the Monastery of Elvangen in Swabia. They did not permit him to have any communication with the Pope and killed the monk Lazarus, who was his messenger. Some of his disciples escaped to Moravia, Croatia and Serbia, while others remained in hiding in Slovenia.

Pope Adrian was never informed of the vicissitudes suffered by Methodios and the new Pope, John VIII found out about them rather late. He wrote off to King Louis and complained that an archbishop had been hounded out of a see which, in his opinion, had always belonged to Rome, and certainly not to Germany. He also wrote to Adalvinus, Archbishop of Salzburg and various other German bishops. After this intervention, Methodios was freed and his persecutors were condemned to life imprisonment.

Back in Moravia

The intervention by the Pope was not the only reason for the release of Methodios. Another factor was the meditation of Emperor Basil the Macedonian, who sent an embassy to Louis in 872, and also the altered situation in Moravia. The new ruler there, Rastislav’s nephew Svatopluk (Svyatopulk), gained independence after a new revolution, one of the leaders of which was the priest Slavomir, the clergy in the Slavic Church of Moravia having always worked hard in favour of the policy of independence for their country.

After incarceration lasting two and a half years, Methodios was set free. Now he did not return to Slovenia, but went instead to Moravia, retaining the title of Archbishop of Sirmium. His many disciples received him enthusiastically in the summer of 873, after a six-year wait.

There then began a period of prosperity for the newly-established Church of Moravia. The great missionary undertook dual tasks On the one hand he continued the training of theologians, clerics and teachers, while on the other he extended his preaching to the broader masses of the population. He placed clergy in all settlements and all the inhabitants abandoned their faith in idolatrous delusions and came to believe in the true God.

He visited all the regions which were then included in Svatopluk’s state and which were inhabited by Slavs: Bohemia, Saxony, Silesia and Southern Poland. He himself baptized Bořivoj, the first Czech Christian ruler. He even reached as far as Kiev, where he preached to the Russians.

This task was carried out under difficult conditions in Moravia, because in 874, after another fierce struggle, Svatopluk was forced to submit to the Germans. The German clergy again became importunate and, in order not to antagonize them, the prince came up with the following means of compromise: he personally would follow the Latin rite, but he allowed his people to attend worship in Slavonic.

In this way, Methodios was gradually estranged from the prince, especially when the latter transferred his capital to distant Nitra. Matters were not improved by Methodios making observations concerning Svatopluk’s moral lapses. For these reasons, and because the prince and many of the nobles around him wished to avoid any cause for a renewed clash with the Germans, the Greek mission found itself in an adverse situation.

Under pressure from two priests, the German Wiching and the Italian Ioannes, Svatopluk addressed Pope John VIII, because he wished to transfer the responsibility for any action onto someone else. The Pope wrote to Methodios saying that he had heard that the latter was not teaching what the Church of Rome had been taught by Peter himself and that he was leading the people into error. He requested that Methodios go to Rome immediately so that he, the Pope could hear his defence and decide for himself. He also said that he had heard that Methodios was celebrating Mass “in a barbarous, i.e. Slavonic, language” (Audiamus etiem, quod missas cantes in barbara, hoc est in Sclavina lingua) even though a letter had been taken to him by Bishop Paul of Ancona forbidding him to do so. The Pope informed he that he was not to celebrate in Slavonic, although he was, of course, free to preach and speak to the people in that language.

The invitation to Rome also justified the Pope’s need to see whether Methodios was honouring the verbal and written promises he had made to the Holy Roman See. Methodios was pressured into going to Rome in 879 for a hearing. At the same time, Svatopluk sent as his representative Wiching, whom he had destined as the replacement for Methodios should the latter be deposed.

But everything changed once he got there. Methodios’ personality was so powerful that he was able to influence matters simply by his presence[1]. It is, in any case, clear that there was considerable confusion in the thinking of the popes of this period. One said one thing, the next another and the policies of the same person, even, were not infrequently contradictory. A contributing factor to John’s attitude was probably the fear that the Western Slavs might escape Roman influence, as had happened, in the meantime, with the Bulgarians.

And so, in a new letter, John VIII ordered exactly the opposite of what he had requested in the previous one. He said that he had examined Methodios on all points and had concluded that he had the faith of the Creed of the Roman Church, which of course, at that time was the same as the Greek. The addition of the Filioque, that is that the Holy Spirit also proceeds from the Son, had not yet been incorporated into the Creed, but it did exist as teaching, mainly among German theologians.

John also requested that the works of the Lord be proclaimed also in Slavonic, because Holy Scripture commanded that we should glorify the Lord not only in three languages but in all. In order to demonstrate his impartiality in the matter, Methodios also translated into Slavonic the Latin mass which was in use at that time so that his Church would have the opportunity to celebrate either the Eastern or Western rite.

He therefore returned, justified, as Archbishop of Moravia. But in order to satisfy the prince as well, the Pope ordered Methodios to consecrate Wiching as Bishop of Nitra and asked for another person, too, so that there would be three bishops in the area and it would thus become a metropolis.

In Constantinople

Many years had passed since the two brothers had left Constantinople in 863. Their intention of visiting it in 867 was never realized, as we have seen. The following year, Cyril had died, while Methodios, labouring ceaselessly among a thicket of obstacles had not found an opportunity to make the trip.

But he always had it in mind to attempt the long journey, for a variety of reasons. In the first place, he wanted to see again the places where he had been born, grown up, studied and lived as a child and young man. Secondly, because he needed an exchange of views with the leaders in Byzantium about the course of his work. Thirdly, because the German clergy were spreading rumours that he had lost the confidence of the Byzantine emperor. And besides, both Patriarch Fotios and Emperor Basil I asked him to make the effort to come to the capital.

In 881, Pope John summoned him to Rome again, because Wiching was continuing his accusations. This time, however, he refused the invitation, judging it better to stop the endless challenges and cross-examinations. This was another reason to hasten his journey to Constantinople.

He made the trip in 881. In the capital, leaders, clergy and ordinary people gave him an enthusiastic reception. They were well-informed about his amazing achievements in the faraway lands of Central Europe and their joy at having the great missionary with them again was beyond description. The Byzantines confirmed his actions in those countries and discussed the future of the Church of the Slavs in the West. Unfortunately, Constantinople was unable to provide any substantial assistance, because between Byzantium and Moravia lay Bulgaria. But he was advised to maintain the autocephaly of his Church and not to tolerate any intervention from anywhere.

Given this opportunity, Methodios was able to bring Fotios up to date on the spread of the teaching regarding the procession of the Holy Spirit from the Son, too. The Patriarch then wrote his famous letter condemning this teaching. Methodios left a priest and deacon in Constantinople to act as his envoys and also to work in the centre for Slav studies.

On his return journey, he went through Bulgaria and met King Boris in his capital at Preslav and gave him advice on the organization of the Bulgarian Church. He promised to send him disciples for this task and these did actually go there, though after his demise.

Final years

After his return from Constantinople, Methodios threw himself into the translation of texts which were indispensible for his Church. It appears that they had stressed this point particularly in the capital.

The vicissitudes which had assailed him, as well as and his numerous duties, had forced him to neglect this task. In 883, he translated the whole of the Old Testament[2], apart from the Psalms, which had already bee translated by Cyril, and the books of the Maccabees. The translation began in March and finished on the eve of the feast of Saint Dimitrios.

He also translated certain Patristic texts and the Nomocanon. In this way he gave the Moravians and other Slav peoples their first written laws, which allowed the organization of social life on the basis of objective and impersonal formulations, without regard to the will of the tribal chieftains.

In 884, a new clash occurred in Moravia, this time dogmatic in nature. It appears that the cause was the publication in the West of Fotios’ letter regarding the Holy Spirit. As did Fotios, Methodios regarded as heretics those who used the term “filioque” and accepted the procession of the Holy Spirit from the Son, too. Wiching reacted strongly and caused Methodios problems. The archbishop was then forced to take the ultimate step of anathematizing him, a decision which was expressed at a meeting of priests.

Svatopluk was so impressed that from then on he became a friend of Methodios’. The unity of the Moravian Church was thus achieved, but, unfortunately only for a short time.

Methodios was at least 65 (his dates are uncertain) when he felt his end approaching. Moved and uneasy, his disciples asked him: “Venerable father and teacher, who among your disciples should succeed in your teaching?”. He himself nominated a well-known disciple, Gorazd, saying: “He is from your own country, a free man, learned in Latin books, [and] Orthodox. May the will of God be done and your own desire, as also mine”.

It is not strange that he authorized his successor. It was simply a wish on the part of the missionary which was approved by all the priests and the people of Moravia. It is very likely that Gorazd was already a bishop, that he had already been elected and consecrated Bishop of Nitra in place of the anathematized Wiching. This was not a matter of the election of a bishop, however, but of his appointment to the archiepiscopal throne.

On Palm Sunday 885, Methodios went to the cathedral church in Velehrad, where the people had gathered. He was very ill. He rendered grace (i.e. thanks) to the emperor in Constantinople, the prince in Moravia, the clergy and his people. Finally he said: “Attend to me, children, until the third day”. And they did.

At sunrise on the third day, he offered his last words: “Into your hands, Lord I commend my soul” and died in the arms of his priests on April 6, Indiction 3, in the year 6393 from the foundation of the world, i.e. 885 A. D.

His disciples conducted the funeral service in Greek, Latin and Slavonic and immediately afterwards they placed his body in the cathedral. And so Methodios was added to the fathers, the patriarchs, prophets, apostles, teachers and martyrs. Innumerable people attended the funeral, mourning the good teacher, men and women, young and old, rich and poor, free and slaves, foreigners and natives, sick and well.

The disciples of Cyril and Methodios

Gorazd took over the governance of his Church with great zeal. But his enemies did not leave him alone for long. From the time that it became clear that Methodios was on the wane, Wiching had gone to Rome to ensure his succession. He convinced Pope Stephen V to oppose the Slavic Church of Moravia again.

In a letter, he demanded the acceptance of the teaching relating to the procession of the Holy Spirit from the Father and the Son. At the same time, he recognized Wiching as the head of the way the Church there was run and forbade Gorazd to undertake episcopal duties until he came to Rome and was recognized by the Pope himself. This would have meant that he was prepared to accept Gorazd as a bishop, but not as head of the Moravian Church. He also forbade the use of Slavonic, which Methodios had allegedly introduced in the face of a ban by John VIII. Stephen was ignorant of the fact that in fact John had, in the end, sanctioned its use.

Svatopluk, to whom Stephen addressed the letter, remembered his old attachment to the Latin rite. He disregarded the anathema against Wiching and became bolder. With his indulgence, the German clergy again raised the dogmatic question related to the Holy Spirit. Gorazd and Clement rebuffed them, but they continued to attack.

Svatopluk, pretending to be in search of a compromise, summoned the leaders of the contending groups to Nitra and told them: “I am almost illiterate and do not know dogmatics. Therefore I shall entrust the Church to whoever swears first that he holds the orthodox faith”. Before he had finished his speech, the Germans- who were obviously privy to the ploy- swore, while the Byzantines refused to give such an oath, considering it idolatrous.

Svatopluk placed the leaders and clergy of the Slavic Church at the disposal of the Germans. All together there were 200. These were either in Nitra, Velehrad or other major centres. Those who worked in small settlements and those who were in far distant areas were not affected, at least not immediately.

The unfortunate clergy were initially tortured and then the younger among them were sold as slaves to Jews, while the older ones, including the leadership, were imprisoned. Those who were sold were freed a few months later in Venice when envoys of the emperor paid a ransom.

From there, they went to Constantinople and then spread out into the Slav lands. Those who had been imprisoned were first handed over to fierce soldiers and then abandoned near the banks of the Danube at a time of freezing cold. Some of them died.

The survivors went their different ways. Those who were of Greek extraction walked the length of the Danube until they reached Belgrade. Among these were Clement, Naoum and Angelarios, who were later to distinguish themselves in organizing the Bulgarian Church, centred on Ochrid.

Those who were locals hid in the houses of relatives and friends or went to regions where they were free from persecution, such as Bohemia and Poland. Among them was Gorazd. In 899, the Slavic Church of Moravia was re-organized with a new archbishop and three bishops. It is likely that Gorazd was the archbishop.

At the beginning of the 10th century, the state of Moravia was conquered by new invaders, the Hungarians. Together with the state, the Church was also dissolved, though remnants of it remain to this day. Throughout the centuries, a pilgrimage has been made to Velehrad in honour of the holy missionaries Cyril and Methodios.

Epilogue

The spread of Christianity among the Slav peoples was rapid and magnificent. After long preparation, it began in 860 and was almost complete in twenty years, apart from Russia where it was delayed for some decades yet.

The episodes which history relates regarding the Christianization of these peoples seem to be random and sporadic activities. Were this the case, it would be inexplicable that, within twenty years, so many things would happen among the Slavs that had not occurred in centuries before. There is, indeed, a connecting link and behind it all can be discerned a power which set in motion a well-planned operation.

This power was the Ecumenical Patriarchate, which put the whole work into motion. The people who carried out the plan were the two brothers from Thessaloniki, Cyril and Methodios, who worked tirelessly among all the Slav peoples: Russians, Moravians, Slovenes, Croats, Serbs, Slovaks, Czechs, Poles and Bulgarians.

Their task was fundamentally religious. Through their actions and those of their disciples, all the Slav peoples entered the circle of Christian nations. But together with Christianity, other civilizing forces were given to them. Together with the ideal of faith, the apostles taught the Slavs love and nobility and instilled in them the spirit of sacrifice.

They gave them their first written laws, with which they organized a polity governed by law and order. They also gave them a written language, ready to use for theology, literature, knowledge and education. This language was the link which united the whole Slavic world.

This is why the Slav nations feel an eternal debt to the two Thessalonian brothers, while Thessaloniki and Greeks as a whole feel justly proud of them.

[1] While this is no doubt true, modern scholarship is inclined to see the whole affair of the treatment meted out to Methodios as part of the continuing power struggle between the Germans and the Church of Rome (trans. note)

[2] As A.-A. Tachiaous points out: “This translation task of Methodius was certainly an achievement, but we must accept that it was not exclusively personal, but was rather a communal effort, which was carried out with the co-operation of disciples, although he would have had the final say and control”. Cyril and Methodius (under publication) (trans. note).