A historical outline of the Athonite Monasticism – Hermits and St Athanasios

13 February 2016[Previous publication:http://bit.ly/23VZd44 ]

The ideological and political orientation of the Byzantine empire at its peak, after the second half of the 10th century, created a favourable climate for the growth of Athonite monasticism. This climate was further improved by the feeling of security that followed after the Arabs were driven out of Crete in 961 and piracy in the Aegean came to an end. By contrast, the once famous monastic communities of Asia Minor had suffered from the invasion and settlement of the Seljuk Turks and the defeat at Manzikert (1071), and went into decline.

Saint Athanasius did not build his monastery in a complete wilderness. The area he chose already had an eremitical monastic tradition, accepted by the Byzantine emperors and with some kind of loose central administration.

It seems likely that already during the second iconoclastic period at the beginning of the 9th century iconodule monks from the neighbouring areas of Macedonia took temporary refuge on Athos to avoid the iconoclast persecution, which however seems to have been particularly mild in this province.

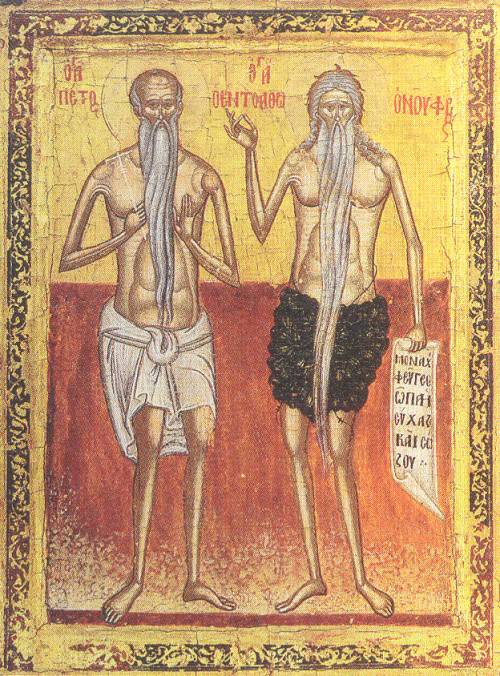

Hermits are first recorded on Mount Athos in the late 8th and early 9th century. These reports are rather vague, but do mention names of particular hermits. The best known of these was Peter the Athonite, who appears to have lived in the area of present-day Kafsokalyvia. Shortly after the middle of the 9th century Saint Euthymius, who later founded the great monastery at Vrastamou (the modern Vrasta) in Halkidiki, spent some time as a hermit on Athos.

Before the mid 9th century the monks of Mount Athos formed a sufficiently large and well-known eremitical community for them to be invited to Constantinople by the Empress Theodora. According to the historian Genesios, monks from Mount Athos were present at the celebrations for the restoration of the icons in 843.

In 833 the Athonite ascetics received their first imperial privileges. An edict of the Emperor Basil I exempted the monks from taxation and barred entry to the Holy Mountain by the inhabitants of nearby Erissos and their herds. In 908 his son, Emperor Leo VI the Wise, recognised the independence of Athos from the great monastery of John Kolovos near Erissos, and confirmed the prohibition on encroachment on the Mountain. In 941-942 the Emperor Romanos Lacapenos instituted the imperial grant to Mount Athos, known as the “roga”, of one gold coin annually. A year later, in 943, Katakalon, the general of Thessaloniki, was ordered by the emperor to demarcate the boundary of Mount Athos. This boundary has remained essentially unchanged to the present day.

By the early 10th century the monks, though scattered throughout the Mountain, had organised some forms of central administration. In 908 we first hear of the protos based in Karyes, the primate, arbitrator and representative of the community to the outside world, and three annual assemblies of all the monks to deal with matters of common concern, to be held at Christmas, Easter and on the fifteenth of August (Dormition of the Virgin). The same period saw the appearance of larger monastic establishments such as the monastery of Saint Paul of Xeropotamou, the monastery of Clement (later incorporated into Iviron) and the Vouleftiria near the present-day skete of Saint Anne.

Nevertheless, the hermits’ life of poverty and solitude continued to predominate, and as the sources of the time mention it was an extremely harsh one. The hermits lived in makeshift huts and survived mainly on fruits found in the forest. This state of affairs still existed in the middle of the following century, when Saint Athanasius arrived and travelled around the Mountain. The description of their way of life in the saint’s Life is typical: The hermits did not cultivate the land; they neither ploughed the land or dug ditches, nor did they possess oxen, asses or other beasts of burden or dogs, but lived in huts of sticks stuck in the ground with thatched roofs. Thus they endured the summer and winter and the howling wind […] Apart from spiritual food, their bodily sustenance was frugal, uncooked and from the mountain; […] they gathered wild fruits and put meals together from these […].

The arrival of Saint Athanasius and the construction of the Monastery of the Great Lavra disturbed the peace of the humble hermits. The internal organisation of the new monastery and its multitude of building and economic activities were completely new to the Mountain. It was the first time that a large cenobium with a centralised administration had been established on Mount Athos.