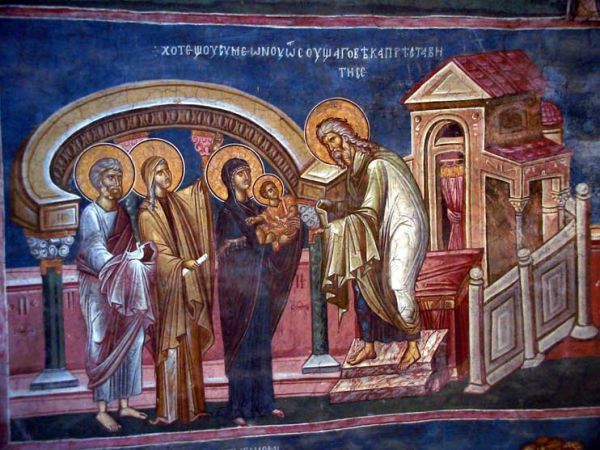

The Reception of the Lord: the feast of freedom

4 February 2021In the hymns of Vespers and the Lity for the feast of Christ’s Reception, ‘Now Lord you let your servant depart in peace’, which was directed to God by the righteous Symeon when he received Christ in his arms, is rendered as ‘Now I am freed; for I have seen my Savior’ [1]. In the face of the infant he was holding, Symeon saw his peace and freedom.

The feeling of peace is a sense of God’s proximity. Peace brings people closer to God and to others. This is shown by the very etymology of the word ‘peace’ which derives from Proto-Indo-European ‘*péh₂ḱ-s’, meaning ‘to join’ or ‘to attach’. More specifically, God-given peace was left by Christ to his disciples as a ‘parting gift’ on the completion of his incarnate dispensation, when he said: ‘I give you my peace’ [2].

As a fruit of the Holy Spirit, Christian peace is associated with love and joy: ‘for the fruit of the Spirit is love, joy and peace… [3]. In other words, it is associated with our happiness and our liberation from restraints. In the Dismissal Hymn for the feast, Christ is called the ‘liberator of our souls,’ who grants us resurrection.

Righteous Symeon was at the end of his life on earth. He had no further life expectancy. Moreover, the space in which his faltering limbs were able to move was also limited. So he was trapped, as it were, in terms of both space and time. How could he say he had been set free?

Freedom implies disassociation from any restrictive factors. It offers the opportunity to expand and move in both place and time. Even more, it offers the opportunity to transcend both place and time. What sort of freedom can you have at death’s door? How free can you be if your movement is limited? That is how Symeon lived. That was his physical condition.

And yet, Symeon had something of great importance within him. He had a hope or, more precisely, an expectation which would be fulfilled within the limit of this fleeting life. He had God’s promise that, before he died, he would see the Messiah: ‘It had been revealed to him by the Holy Spirit that he would not die before he saw the Lord’s Messiah’ [4]. This is what he was waiting for.

The expectation of the Messiah was what gave meaning and sense to the life of righteous Symeon. And when this expectation was met, he was able to ask his master to dismiss him, to let him die. He wasn’t waiting for anything else. He’d seen what he’d been expecting. There would have been no sense in any extension of his life on earth. This is why he asked to be dismissed.

Dismissal is the liberation from some kind of authority. It’s becoming unshackled. But, in itself, dismissal also has a negative aspect. It’s a rift. And a rift implies pain. Even greater pain is implied in the rift caused by death. ‘I weep and lament when I think on death’. ‘What a struggle the soul has when it separates from the body’. Symeon, however, neither lamented nor contemplated any struggle. He was dismissed in peace.

People aren’t happy and peaceful when they’re dismissed at random from their place of work. But they don’t mind when the dismissal takes place amicably and by mutual consent. When the dismissal is completing a specific task and then entails embarking on another one which is better and superior to the former.

When the exit from this fleeting life is linked to the entry into life without end, then death takes on a positive aspect; it becomes a festival. This is why the deaths of the saints of our Church are celebrated with feast-days. Saint Paul expresses a three-fold exhortation to the faithful: ‘Rejoice always, pray continually, give thanks in all circumstances; for this is God’s will for you in Christ Jesus [5]. This means that joy, prayer and gratitude are to be seen as an indivisible triune action.

Righteous Symeon calls the dismissal he’d been expecting ‘peaceful’, because it fulfilled the promise made to him by God regarding the salvation of all peoples. His words reveal a man of universal stature. They show that he embraces all peoples, that he’s at peace with all humankind and that he founds this peace, like the peace he bears within himself, on peace with God.

As the hymn in Vespers puts it, the cause of Symeon’s experience is that the person he’s taken into his arms is ‘God the Word, from God, incarnate for us’. The incarnate God the Word unites us with God, brings boundless eternity into the finite world and changes our death and decay into incorruption and immortality.

These events don’t have any divine meaning. They aren’t to do with God but with us. God became human in order to save human nature.. He became one of us, in order to make us gods. He is God by nature and has made us gods by grace. He’s given us his uncreated grace and his unending life. He’s made us sharers and participants in his love and bliss.