The Easy Way isn’t a Friend of our Spiritual Life

22 December 2018Our modern civilization prides itself and boasts about the fact that it’s managed to improved the everyday lot of humankind. From our primitive ancestors, who strove to dominate the rest of creation in order to survive, we moved on to the great scientific and philosophical advances of antiquity (in Egypt, Babylon, Greece, Rome and so on). A good deal later, we saw the transition to industrialization in the 18th and 19th centuries and the advent of machines in our daily life. And now, in our own day, we’ve reached the so-called ‘scientific revolution’, where we’re trying, through computers, IT and robots, to study and configure things that, only a generation ago, would have been considered unthinkable or the stuff of science fiction.

The common denominator of each discovery (supposedly, at least) is the improvement of our life, directly or indirectly, so that everything happens more easily, more quickly, more collectively, more accessibly, for longer, at less cost, better quality, more readily understandable and useful, with whatever that means for the process of advancing and transitioning from the traditional and the manual to the technical and electronic.

Many experts are upbeat and supportive of this course of events. Some are more wary or are baffled by developments, while others are completely pessimistic and opposed to these developments. The latter are attempting to preserve traditional methods and to resist these electronic advances and our robotization.

With all this in mind, we come again to our own, ecclesiastical matters. Do all these developments and circumstances regarding people today have anything to do with the Church? If so, to what extent are they tolerable? Is it anachronistic and obscurantist (as the Church is often accused of being) to make an effort to resist, or even to adopt them with discretion and moderation, with reference to particular conditions and criteria? What are the boundaries? What is allowed and what’s a red line?

The Orthodox Church knows full well that, historically, it functions in this world, but isn’t of this world. As a companion, it follows, and often takes upon itself, the vicissitudes of people and the discoveries they make, but is also aware that it was founded by Christ, Who was both God and human. We come from the future, the Kingdom of Heaven, of which we have a foretaste in the here and now through our liturgical, sacramental life and also through the love between the members of the local parish community or see.

Culturally and politically, as we mentioned at the beginning, humankind has passed through many stages and is continually making advances. Because the Church isn’t only a place of worship, but is also the members who constitute it (clergy and laity, as a theanthropic organization), it adopts some of the scientific developments (such as, for example in architecture and the construction of churches, the printing press and so on), but rejects others as being incompatible with its theological aims (such as euthanasia and abortions). Even as regards subsidiary, though substantial, matters such as the use of wax candles or oil lamps inside the church. For the Orthodox, the use of wax candles and oil and wicks for the lamps and so on is always to be preferred.

One thing is certain, however, and this is that the Orthodox Church has never hindered or battled against any scientific discovery that people have made. In any case, through its education, its culture and its material grants, or its provision of scholarships to young scientists, it has contributed to the creation of new discoveries in a variety of fields. It may disagree or be cautious on some matters, but it will never, on an official level, attempt to destroy or oppose anything dangerous to our psychosomatic health and spiritual well-being without putting forward its own arguments and proposals. This, in itself, says a lot. If some people commit crimes against humanity and science in the name of the Church, they have no real relationship with the true body of Christ.

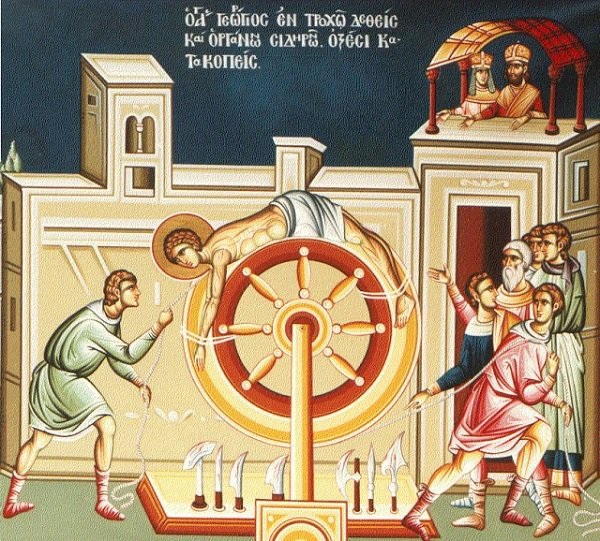

Beyond all that, however, and apart from secularization (which is an attempt by the structures of worldly society to change the Church from within) there’s a danger which is both hard to see and very perilous. This is ‘the easy way’. We’ve learned to press a few buttons and everything happens automatically. Everything has to do with us humans and our fabricated, not our real, needs. Need means that if I don’t eat or drink, I’ll die. But if my cell phone isn’t an iPhone, or if I don’t even have one at all, I’m not going to die over it. This is an attitude that many of the faithful among us, consciously or otherwise, try to bring into the spiritual life. We don’t like difficulties, asceticism or the Cross. What we all want is the elevator, but the Church always talks about the ladder of the virtues. We don’t like listening to long homilies, or making much of an effort. We want it all and we want it now, easily and quickly. Patience, forbearance, humility, asceticism are words we don’t know and we avoid them.

Christ spoke to us of the ‘strait and narrow way’. Our Fathers say: ‘Give blood and receive spirit’. So there’s no easy way in spiritual matters, my friends. Unfortunately, it’s now easier to travel to the moon than it is to look into our heart or see our neighbour a few feet away. But that’s what it is that saves us, in the end. Otherwise, we’re always threatened by the temptation of Babel, in other words by the conquest of God through our own, technical means. But God isn’t conquered, He’s given to the pure, the humble and to those who patiently knock and implore in prayer and in the observation of the commandments and the ascetic life. Let’s open our heart and avoid impetuous reliance on science or on pride that we’re able to doing anything we want. There’s no human invention that doesn’t have long-term side-effects, either on the environment, our health, or on the issue of our salvation, if we get rid of God and make ourselves God, without the true God. Amen.