Tangled Web

30 May 2014It’s being reported in British newspapers that twin five-year-old girls who effectively have three mothers are at the centre of a custody battle between the two ladies who brought them into the world.

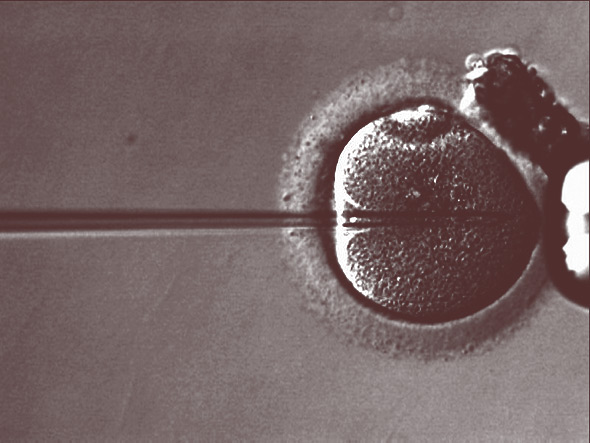

The children live with the woman who gave birth to them, (A), but were conceived from eggs donated by her former ‘partner’ (B). They have since been adopted by her current partner (C). Under the Human Fertilisation and Embryology Act 2008, the egg donor (B) has no legal status as a parent. But she is fighting for a court order which would allow her part-time custody of the girls and would also recognise her as a third legal guardian.

The twins now have a birth mother, an adoptive mother, a biological mother and an anonymous father (D), with whom they are forbidden by law to have any contact until they are 18 years old.

A court heard that the birth mother (A) and genetic mother (B) had an ‘intimate relationship’ after meeting in the 1990s and continued to live together after their relationship became platonic. When one of them (A) struggled to conceive, the other (B) agreed to donate her eggs, which were fertilised using an anonymous sperm donor (D) in 2007. But when relations soured in 2012 and the genetic mother (B) moved out, she found she was not recognised as the twins’ legal parent.

The little girls continued to live with the birth mother (A), and she later entered a civil partnership with another woman (C), who was subsequently made a legal parent of the twins by the courts.

In the first hearing in the custody case, at Portsmouth County Court last August, Judge Helen Black ruled in favour of the birth mother (A), saying the egg donor (B) was ‘not a parent of the children and that her status should not be elevated in that way’. She raised concerns about how the egg donor (B) ‘would operate her parental responsibility if given it’.

But she (B) challenged the decision in the Court of Appeal, insisting she had a right to look after the twins. She argued that she had raised the girls for the first couple of years of their lives when she was still living with the birth mother (A), who had returned to work.

In March, three judges upheld the appeal, claiming the initial judgment had been built on ‘wobbly’ foundations and the full evidence had not been heard. The case will now be sent back to court for a fresh hearing. Lady Justice Black (not Helen, this time, but Jill, and no, I don’t know if and how they’re related), said ‘… it is very sad to see [childhood] being allowed to slip away whilst energy is devoted to adult wrangles and to litigation.’

To further complicate the case, the genetic mother (B) used some of the embryos that were created to conceive the twins in order to have herself impregnated. This means that her toddler, daughter (G), is a full sister to the twins (E, and F). Meanwhile, a family solicitor, Marcus Malin, said ‘People must go into these kinds of agreements with their eyes wide open’. It might also help if they had their brains switched on.

Mr Malin said sperm donors must be aware that biological fathers could be liable for child maintenance. Given this, it seems that the sperm donor (D, remember him?) is now in the position of perhaps having to provide what might be a considerable amount of money for the care and upbringing of the children (E, F and G), though he won’t have any contact with them until they’re 18, when, no doubt, they’ll turn up on his doorstep with a request for help with their student loans. Perhaps accompanied by the three mothers and any other partners who have since become involved, all demanding he ‘do the right thing’.

This sad story has been allowed to occur because the Churches in Britain have lost the moral authority they had until very recently, basically because they were caught unprepared by the speed at which society has changed in recent decades. Although I’m not suggesting at all that the same collapse is likely in Orthodox countries, we need to protect against it by acknowledging the dilemmas of modern life. Like many other Orthodox, though by no means all, I would be in favour of a radical re-assessment and re-evaluation of the position of the Church on the vexed moral problems of today, not out of a desire for change, necessarily, but precisely to preserve respect and moral authority. Because any such review would, of course, be carried out by eminent theologians, canon lawyers and Church historians from all Orthodox countries, who would compile a report to submit to the bishops, who would then pronounce the Church’s position. If they chose to reiterate the traditional view, the exercise would not have been a waste of time. Contemporary concerns would have been addressed and the Church would be all the stronger for it and better able to give an authoritative answer when confronted by people whose sole moral guideline seems to be: ‘I want to do it, and I can’. This doesn’t make them bad people, but, surrounded by them as we are, it does suggest that we should be trying to reinforce what order (and sanity) we have in our ever less cohesive society before we all slide into absurdity.

W. J. Lillie