Environmental Poverty and Personal Responsibility. Science meets the Discourse of the Saints

3 November 2017The degradation of the quality of the environment in which we live is an incontrovertible fact. For decades now, many people have recognized the importance of this, though, unfortunately fewer have been moved to take practical steps and undertake action, even though we all suffer the consequences of this decline.

Scientific discourse is unavoidably involved in this question. In the first place, circumstances are such today that it’s accorded, as if by right, a part in any kind of discussion which takes place in the public sphere. And also because technological applications shoulder a large part of the burden of responsibility for the ecological crisis, or because the solutions to many of the problems are expected to come from scientific thinking.

In recent years, an intense ecclesiastical discourse has evolved around this particular question. On a theological level- institutional (indeed at the highest possible level), or even in the sphere of action within parishes and among ordinary believers- ecological concerns have risen dramatically. This development can only be considered positive and all that remains is to put its beneficial results into practice.

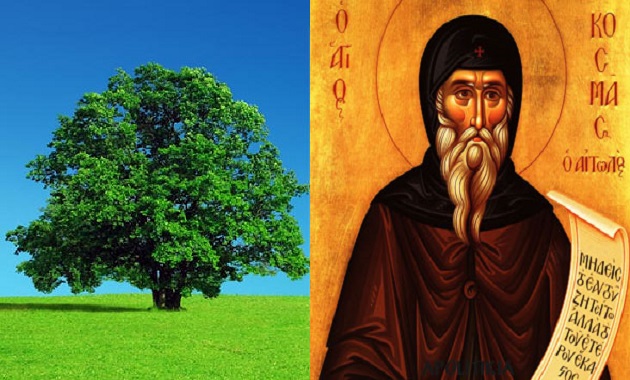

It’s impressive how respect and love for nature informs the discourse, the spirit and the life of those people who have imbued their existence with the spirit of love and reconciliation. Almost 250 years ago, Saint Kosmas Aitolos [in one of his prophesies] said that people would be poor, because they didn’t love trees. And some 100 years after that, Fyodor Dostoevsky, another great man and the “saint of Russian letters” said that he couldn’t understand how anyone could pass a tree and not rejoice at its sight.

Real sensitivity to things, therefore, is demonstrated whether there’s a crisis or not. And complete spiritual flaccidity, on the other hand, is obvious whether there’s a need to deal with a problem or not. Many saints lived in harmony with their environment even though there were, in their times, no indications of its misuse and abuse. On the other hand, today, when the danger of an ecological catastrophe is very much present, many Christians continue to be indifferent towards the environmental consequences of their way of life. If, as is said, the proper way to honour saints is to imitate them, then today, more than at any other time, we should transform our concerns and apprehensions into tangible actions and not resign ourselves to pious wishes. Promotion of mild forms of energy, preservation of flora and fauna, of wild life and aquatic resources, as well as the cultivation of an anti-consumerist spirit are merely a few, token ideas in this direction. Besides, action is always a self-feeding process: through it, new opportunities arise.

The solutions being proposed for dealing with the ecological problem are neither unambiguous nor one-dimensional. Let’s see, for example, what’s happening in a new field, that of Environmental Ethics. It is well known, for example, that, modern Western thought and practice is dominated by an anthropocentric spirit, which we call humanism. In the context of the spirit, a corresponding anthropocentric philosophy has evolved which considers that humankind is the centre and reference point of the world. This is equivalent to the idea that nature is accorded a relative moral value, which is constantly changing, depending on human needs and inclinations.

In Greece, we continue to think that this spirit is responsible for much that is wrong. We also usually believe- without of course admitting it- that it is only we who understand this and that we should be scathing about it. But this is not entirely accurate. It has been remarked in many places in the Western world that this untrammelled dedication to serving people’s inclinations has led to many social problems, among which the issue of the environment holds a prominent place. And there is a variety of sub-sets within this opposition movement (Social Ecology, Biocentric Ethics and so on).

… But when you live and think with a Christian world-view, you have different starting-points and different destinations. In particular, as regards illnesses, both those which are in the offing and those which have already appeared, you can’t simply stand still in the face of the threat, but you have to dig into the deeper significance which it entails. Because among the other paradoxical things the world perceives in the teaching that comes from the Gospel principles there is also this: that illness is seen as a blessing, as a cause and intermediary of salvation. Rather like something else we’ve heard a lot recently: that we should see the [economic] crisis as an opportunity. Because, while it’s true that the Church doesn’t want illness and countenances special prayers for the restoration to health of those who are sick, when people actually do become sick it advises them to use the opportunity for the benefit of their soul. Gregory the Theologian declares: “Better a rightly-viewed illness than unbridled prosperity” (Epistle 35) and, in another case, urges us to prefer “blessed sickness” to “heedless health”. Saint Basil the Great also candidly prefers an extension of bodily illness in the hope that the people concerned can become aware of their true condition (Shorter Rule, 140).

And this reasoning is not theoretical, not is it the privilege of only a few enlightened ascetics or other charismatic persons who have reached a certain measure of spiritual perfection. This is confirmed by another aspect of the research we referred to: when the question was asked- of Greeks- as to who was the most environmentally aware, the profile of the “champions” indicated that they were women of 55 or over, with primary or secondary education and who came from semi-urban or rural communities[1]. Equally impressive as this finding is its interpretation: it appears from similar research in other European countries that the environmental sensitivity shown by women is due to their combined role as mothers and grandmothers, and is linked to unease over degradation and a concern for the future of generations yet to be born.

And it is precisely here that we encounter another central point of Christian tradition: relationship as a channel for personal fulfilment and also renewal. We understand the Triune God as a relationship of persons, the plan of Divine Providence as the result of the relationship God wishes to have with His creation, the very essence of love as the culmination of a relationship. The archetypal symbol of a mother who, looking at the wound of mother nature, sees the ongoing woes which cut off this generation from those of the future and this meets the theory of people as beings who are at the border between created and uncreated and, as a priest of nature, brings it in thanks to the common Creator. It encounters the common pain of Saint Kosmas and of Dostoevsky regarding trees, that is the whole of nature.

On another level, it comes up against the pain of Patro-Kosmas, who couldn’t bear to remain any longer in his monastery and wanted his relationship with his fellow human beings to be stretched to its limits: “Hence, I left my own progress, my own good and went out to walk from place to place and…I said: ‘Let Christ lose me, one sheep, as long as He gains the rest. Perhaps God’s mercy and your prayers will save me, too’”. Maybe it also comes up against the activist Papa-Yannis (Ikonomidhis) from Inofyta in Viotia, who is fighting all alone- in this world- to save the population of his region and from the unconscionable heartlessness of its industries[2]. This is a priest who clearly doesn’t share the view that the environmental problem will somehow be solved in a magical manner once we’ve “restored God to our hearts” as he puts it.

Scientific thought also seeks relationships. It attempts to reveal the interconnections of the things of this world and to uncover the logic they conceal. Certainly there are still a lot of links missing, but, with what it has achieved so far, it’s managed to defumigate many nests of ignorance and superstition which used to torment people. Indeed, recently it has turned its attention to a more specialized concept of relationship. It is studying the function of networks, and is attempting to understand the world not as a sum of fragmented and isolated pieces, but as a complete woven fabric of interlinked functions, and recognizes that social networking may reinforce the defences of the human organism in a multitude of ways.

[1] The point would be worth making, however, that the reason why younger people seem not have the same “high degree of environmental sensitivity” is not because they’re really less involved but because they judge themselves more harshly than their elders do themselves.

[2] Together with the chemist Thanasis Pandeloglou, he contributed to the discovery of the largest ecological crime- even on a European scale: they contributed to the recognition of the toxic waste which was polluting the aquifers of the region with carcinogeous hexavalent chromium and other dangerous heavy metals For years now, he’s been fighting to spark awareness of the crime being committed in Inofyta, Thebes, and Vayia, but also in Tanagra, Avlonas, Dilesi, Oropos and Halkoutsi.