Echoes of Athonite Chanters: Deacon Dionysius Firfiris (1912-1990)

9 October 2014Deacon Dionysius Firfiris came to the Holy Mountain at the age of eight, when as an orphan he was brought there by his uncle, the monk Fr. Haralambos. He was initiated into the spirit and essence of Byzantine music by Elder Dionysius, his spiritual father, and proved himself not only his equal, but surpassed his skill. His gifted voice left an indelible mark on his era, spreading joy and moving the souls of the Athonites.

Fr. Dionysius proved to be a shining continuation of the style, spirit, and interpretive tradition of the renowned older musicians of the Holy Mountain

I was an admirer of the ever-memorable Deacon Dionysius (Firfiris) from 1950; from the time, that is, that I first heard him chant at a great feast at his monastery (the Holy Monastery of Koutloumousiou), and from the first note I nearly “lost it,” which was how everyone felt when they heard him for the first time. This was because of the sweetness of his chanting and because of the completely unique tenor of his very melodic voice, which not only affected my ears, but the depths of my soul and being.

When I moved to Karyes a few years later, during my tenure at the Secretariat of the Holy Community, I attended services at the historical church of the Protaton and had the opportunity, not only to get to know him better, but also to become friends with him.

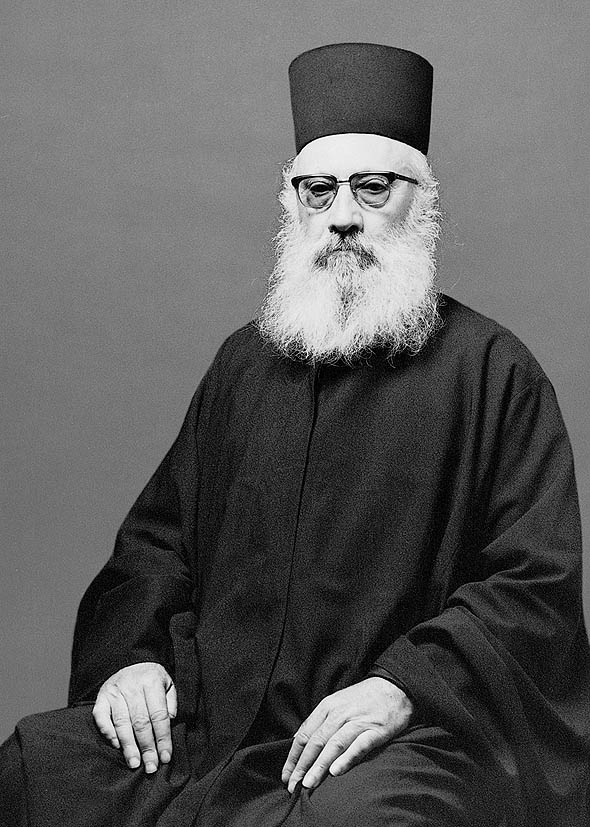

Fr. Dionysius as a worker at the shop in Karyes (1957), image by Chrysostomus Dahm

Oh, how lucky I considered myself, especially during the first stage of our friendship! At that time he would signal to me to come closer and, initially, to help keep the drone note. A little bit later, he encouraged me to hold the book and to chant along with him from the stall next to him! My bliss was indescribable, when I considered how small, common, and little I was, and yet I was deemed worthy of the honor of approaching such a great and capable chanter, who would ascend to ethereal heights…

That friendship continued admirably and without lessening until his old age and his passage towards the Lord. Beyond the fact that I regarded his friendship as an honor, and accepted it as a gift and show of respect on his part, my soul was constantly compensated with a joyful richening, and my hearing with his angelic melodies. Is it a small thing to be friends with, and close to one, whose title as “Great” is one that is passed on, and which, as such, is recognized and agreed upon by everyone?

Those of us that knew him, and enjoyed his chanting from the time of his youth, believed that the Panagia Theotokos, the Lady of that place, gave him this gift since, at the age of eight, he dedicated himself and passed his entire life in Karyes and, in particular, in the Hermitage of the Prophet Elias, just about a hundred meters from the church of the Protaton and from the enthroned miracle-working icon of the Axion Estin that is there. She knew that he would chant hymns to her there so beautifully, thousands of times. He would add light to her feasts and celebrations and would draw the faithful to the Protaton for seventy whole years.

Thoughts and Feelings After the Repose of the Deacon Dionysius

From one end to the other, the Athonite peninsula was shaken by news of his repose in the Lord. There was not an Athonite monk or a music-loving layman, among those who had been lucky enough to have heard him or knew about him, who did not mourn the loss greatly. There were very many who went to great lengths to fulfill their desire to be present at his funeral, and to give him their last embrace and greeting.

However, that which ruled in my mind at those moments during the funeral service, which came from my unworthy person, and that exuded from that august scene and made us inconsolable, was nothing but the realization of the consequence and the situation: that from then on, we would never again hear, in the Protaton in Karyes, in the catholicons of the holy monasteries, and in the chapels of the hermitages, the voice that gave joy to our souls, his blessed mouth singing hymns to the Saints so poignantly, supplicating the Virgin Theotokos so movingly, in such imitation of the angels sending up the thrice-holy hymn to the Holy, Life-Giving Trinity, One in Essence, and so properly thanking and glorifying Christ the Savior.

The miracle-working icon of the Axion Estin from the Church of Protaton, Karyes, Holy Montain

What was it that, seeing the blessed one laying in front of me, evoked scenes and situations from years past that came to my mind and imagination, from the funeral procession of another of our beloved brothers, Kareotos, during which I was still a chanter in learning and simply followed the hymns. This was during the period that he was at his height, and chanted his most perfect hymns, as he led the whole choir.

The prescribed melody, that slow version of the hymn of mourning, the “Holy God” had been sung, and there still remained some time as they made their way towards the newly opened tomb, his soul desiring to chant, until the very end, a completely unique melody in the sixth tone, from a notebook in which he had divided up hymns. I remember being so incredibly amazed by his work that I asked permission to copy the manuscript. Now, I am not able to find it though. So many years have passed, but I did not forget, it began like this, “Viewing myself speechless and breathless lying there, weep everyone, brothers and friends, relatives and acquaintances. For yesterday I sang with you and suddenly my terrible day of death came upon me…” and he ended, “But I ask everyone, and I beseech, pray to the Lord that He would not condemn me to a place of torment, but would place me there in the light of life.”

What an amazing hymn that was, dear Lord! He literally floored us; our emotions moved very slowly, and it was as though we were translated to a sphere of otherworldly realities, with eschatological vision and power. It was as though all of our spiritual powers, and all of the other actions of our souls all at once stopped, attending to the brother that was being buried, and taken up, engrossed by the seriousness and great value of the realities of what takes place right after death, of which the Deacon Dionysius was so sweetly and passionately teaching us about, moving us all from within, down to our very bones.

And, better than anyone else, the blessed one could do this, through the gift of his sweet voice, through the meanings that came through the way he sounded the words and phrases, with his unmatched rhythm, with his dexterous passing from one part to another, as difficult as these might have been, and with such great precision, and his completely unique style, executed with his own coloring and form. It was then, I remember, that I regarded as inconceivable his absence from worship and the hymnological service of our Athonite world; it came to me suddenly and I exclaimed so my neighbor could hear me, “You, Dionysius, you will never die.” The blessed one heard it, and it was sufficient that he smiled faintly.

Now, I could see him “voiceless and dead,” and my heart was shaken. Chanting and reading the service, I struggled to keep back sobs and tears. On the Holy Mountain we are not used to crying during funerals, for the memory of death is regarded as a great gift and a part of daily life, according to the Pauline phrase, “I die daily,” (1 Corinthians 15:31), and “if we died with Christ, we believe that we will also live with him,” (Romans 6:8). So, we ask God to give it to us, and because we regard the fact of our final breath and our earthly death, not as something sad and painful, but the moment of our liberating passage “from death to life,” (John 5:24) that we are all waiting for. We regard sadness for the reposed as only appropriate for “the rest of men, who have no hope,” (1 Thessalonians 4:13). We, however, have faith in the life after death and in just rewards.

And yet, I found it difficult to comprehend his final departure from amongst us, to such an extent… that it was a scandal. With understanding and grace from God, the hardy and imposing Deacon Dionysius had, with such a beautiful voice, and so movingly, chanted that eschatological hymn of exodus, regarding which I have previously spoken. His execution was so wonderful that it would have been worth waiting your entire life to hear, and enjoy, such an otherworldly and heavenly harmony.

Certainly, the good and proper knowledge of the dogmas of our faith in general, and the understanding of these truths, as much as is humanly possible, effects the salvation of our souls, and our state and perspective after death. These are the result as much of systematic catechism and teaching on the other hand, as our personal study “in our room,” (Matthew 6:6), in the fear of God and through asking for His enlightenment and grace, on the other hand. No one, however, should have any doubts that Byzantine chant, when it is ecclesiastically and piously used in service of the hymnology of divine worship, also takes on a power of grace and the ability to educate, to depths, in fact, where it has complete success in bringing man to God; and through hymns it can elevate the souls of the well-disposed faithful to heavenly realms. When this happens, it makes souls very open to the truths being melodiously taught. This method is certainly unusual, but unquestionably excellent and successful. How it works, how it creates salvific conditions in the souls of the well-disposed flock, and what the means are by which it initiates the faithful into knowledge of the divine is a mystery, but it has been confirmed by the great Fathers and Teachers of our Church.

If even our less talented chanters are able to help us approach the truths that are contained in all the hymns and troparions of our Church, then we need to consider what chanters of the quality, and with the artistic dexterity, of the ever-memorable Deacon Dionysius are able to accomplish for the good of our souls.

When my dear friends, Elder Kosmas and Papa-Chrysostom, who were part of Deacon Dionysius’s brotherhood, thanked us for participating in the funeral and memorial service of the reposed, they passed out cassettes taped from the blessed one’s various classes. It was the best gift they could have given to those who had hastened to honor, with their presence, the one who was headed heavenward. Those present also demonstrated their amazement at the chanter who, in our generation, had the most beautiful voice of all, and not just on the Holy Mountain, but I believe, and many others agree, in the whole world.

His God-Given Talent

Hyperbole, one could counter. We will justify him, however, simply because his musical performances were superseded only by the surprise and lively enthusiasm that was always expressed by those who listened to him. From the depths of his soul, the remarkable creations and fruit of the throat, mouth, and lips of the ever-memorable Deacon Dionysius Firfiris were the songs and hymns, “more to be desired…than gold, Yea, than much fine gold; sweeter also than honey and the honeycomb,” (Psalm 18 (19):11); things, that is to say, that are beyond any comparison.

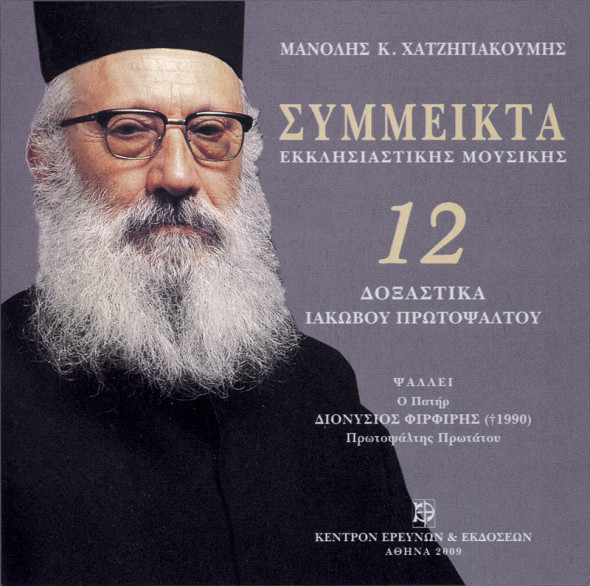

Symmeikta, a CD collection that features the best interprets of byzantine ecclesiastical musicdedicates a few volumes to Fr. Dionysius Firfiris

These hymns were, in any case, unsurpassed in our generation (the second half of the twentieth century), and no one else could have matched or copied them. He himself was a modest monk, though he was also a gifted chanter who, through his chanting, made an indelible mark on his era, and on our era. He gladdened and directed the souls of the Athonites, and was justifiably regarded as a modest adornment of Athos and its monasticism.

Deacon Dionysius was very much to blame, when for reasons of modesty, he refused the official offer (in 1960) of (also ever-memorable) Metropolitan Nathaniel of Militoupoleos (who was my predecessor as Principle of the Athoniada School), for us to accompany him to Athens and to have him work with a celebrated recording studio, so as to produce two or three recordings of his musical interpretations (at that time, the use of 33s was commonplace). He remained unyielding. “Are we for such things? Why should we go to Athens?” It was incredibly discouraging, for we desired to save this rare gift… What a shame! He wronged himself, but this was the smaller evil. The greater evil, and difficult to forgive, was that he made it forever impossible to treasure, in the spiritual treasure chest of the greatest gifts of our Holy Mountain and of the Orthodox Church more widely, his vocal and interpretive gift, as a priceless and eternal inheritance.

Who, of those that remain from that period, could forget the shivers and hairs that stood on end during services at the Protaton, and at other places? Could anyone forget the way our hearts leapt, and the unspoken changes and experiences that took place in our souls, when we heard him, especially during Great Lent, chanting with the style, the rhythm, and the color that only he knew, and the grace of which he was the bearer?

So many decades have passed, but it is as though we hear him now, moving us, filling us with joy, directing us, through his interpretations (unable to be reproduced by anyone else) of the hymns of Palm Sunday, of Holy Week’s troparions, doxastikons, and other hymns, “Today, the grace of the Holy Spirit abides with us…”, “Six days before the Passover,” “May my soul not grow weary, oh Bridegroom Christ, but burn with virtues like a lamp,” “You are the Son of the Virgin…,” “When the sinful one offered myrrh,” “When You, oh Lord, ascended the Cross,” “What an amazement to behold”!

A set of Symmeikta collection dedicated to Holy Mountain

Though your heart was made of stone, it would have shivered at the sweetness of his otherworldly voice, and at the obviously personal way that he had of executing each section, each lesson, of expressing these things that we were unable to explain, since we lack inspiration and are mortal. We were satisfied to describe them and to give them the name, “creations of Firfiris,” even though we knew that they were the inspired works of Peter Philanthidou, the sweet-voiced one, a friend and admirer of the Holy Mountain, chanter and great teacher of music of Panormou Kyzikou, of Constantinople, and whose work was divided into parts at Athoniada, and published in Constantinople in 1906, in two volumes.

Though our feelings might vacillate, we felt true joy when we heard the Paschal hymns, such as “Christ is risen,” the slow version of “This is the day of resurrection,” “The angel cried to the Lady full of grace,” or the doxastikon of the praises in the fifth tone, of St. George, “Spring has arisen…,” which he chanted at the Holy Monastery of Zographou, or in the chapels of the hermitages in the area around Karyes that were celebrating feasts, such as that of the Elders of George (of Nicodemus), and of Ananiou (of the Skourtaion), where each anniversary they would say, all in agreement, “So you decided to come out to join us in the choir….”

In my mind, in any case, and in my suffering heart, as long as I live, and until I die, all the doxastikons of the feasts of the Lord, the Mother of God, and all of the Saints of Mount Athos gloriously celebrated, will continue to resound in my ears in exactly the lively and excellent manner with which he chanted them. This is most especially true of this hymn of the feast of the Holy Transfiguration of the Savior, “A symbol of your resurrection,” which he chanted each year at the Holy Monastery of Koutloumousiou, and of the hymn for the Dormition of the Theotokos, “Your immortal dormition,” in the historical church of the Protaton.

In the same way, all of the hymns of the liturgy in all the tones will resound in my ears and inner depths, especially the ones that he himself composed and performed, which he had the habit of chanting when he was asked to chant at the patronal feast of the Holy Monastery of Iveron. At these feasts, the blessed Papa-Neilos, who was distinguished for his gift of speech, and who lived the ascetic life at the Iveron Skete of the Honorable Forerunner, had given the name “much-remembered ones” to these original melodies. He interpreted this name through the irmos of the ninth ode, “In Thee, oh Pure Virgin, the bounds of nature were overcome,” whose melodic perfection proved this name to be exactly accurate as it left all of the feast-goers, Athonite monks and lay pilgrims and visitors, amazed and as though stunned.

His Musical Background and Education

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Dionysius Firfiris (the First) was the elder of a brotherhood in Karyes at the Hermitage of the Prophet Elias. This brotherhood came to be known by the name of this elder. He was a sweet-voiced chanter with great knowledge of Byzantine music theory. He did not leave any of his disciples without a musical education, especially those with the gift of a beautiful voice. Talented beginners from other elders were also sent to him to learn music.

It was through this elder that, from the time he was a child, Demetrius Koukos (the future Deacon Dionysius Firfiris) was initiated into the spirit and essence of this divine art. It was here that he was gently taught all of the mysteries of the musical phrases and how to execute them. From early on, day-by-day, the brotherhood was increasingly amazed at how the young student proved himself to be equal to, if not greater than, his elder and teacher. And when the time approached for his monastic tonsure, according to the common desire, the decision was made that his name would be changed to Dionysius, as was the custom.

Some time later (from 1935 to about 1945), desiring to develop his skills further, he sought out and found a second teacher. This teacher, Elder Synesios of Stavronikita Monastery (the “Second Koukouzeles” as the Athonites called him) was believed to have a better voice than any of the chanters of recent centuries. Dionysius also learned from Fr. Gabriel, the great teacher of Byzantine musical theory.

Elder Dionysius (the First) lost his vision very early on, so that everyone referred to him as the “the one without vision,” so as to distinguish him from others that bore the same name. But the All-Good One, as if to compensate him in some way, in addition to increasing the vision of his soul, also provided him with an exceptional memory.

We make the sign of the Cross and glorify God every time we see him approach and, with precision, go into the central [chanter’s] stall to lead the choir with ease and joy. His disciples stand around him and chant with him, Haralambos and Dionysius, who hold the book forward. The elder holds the lit candle in the center, but only for the others to see! And the blessed one has not lost any quality or energy in his chanting, not even one little mark was missed, nor from his rhythm and timing was any quality lost.

Of the elders of the Hermitage of the Firfirises, my insignificant person was only blessed to meet Fr. Averkios, and following him, as just slightly greater, Fr. Haralambos. It was through the initiative of Fr. Haralambos that the Deacon Dionysius found himself on the Holy Mountain. And this was how it happened…

The little Demetrius was orphaned and left completely defenseless at the age of eight. This pushed his uncle according to the flesh, Haralambos, with the agreement of the brotherhood, to go to their homeland (Revenikia, Great Panagia, on Halkidiki), to pick him up and take him to their hermitage, and from that point on, he acted as his father and teacher from the alphabet on up.

Insignificant though I am, I arrived in time to meet the Elder Haralambos and to hear him chanting with our beloved Deacon Dionysius. He was the only one that he allowed to be beside him. This was not because the deacon did not accept others, nor did he allow his uncle to be there simply out of respect, relations, and thanks, but because their voices blended well. Also, because he had memorized, and thus had easily at hand, all of his beloved nephew’s musical pieces. And finally, because he had an innate sense and understood each of his melodious paths. He knew when, what, and how Deacon Dionysius, vocally and technically, would improvise and create.

Offer from Archbishop Chrysanthos to be the First Chanter at the Metropolis of Athens

At some point, I heard Elder Haralambos tell the story of the temptation that their brotherhood suffered at the hands of Archbishop Chrysanthos of Athens (who was from Trebizond). Deacon Dionysius was just twenty-seven (he was born in 1912, tonsured a monk in 1928, ordained deacon in 1930 by Bishop Photius of Moschonision, and reposed in the Lord on 24 March 1990) when the Archbishop visited the Holy Mountain in 1939. While visiting the Holy Community, the Archbishop attended the Sunday liturgy at the Protaton. He was so affected by his experience, and amazed by the sweetness of the chanter’s voice and the unique style of the young deacon and chanter Dionysius, that he immediately expressed his desire and did whatever he could to have him come to Athens. He promised to immediately set him up in the capital’s Metropolitan church, to take care of his studies, to lead him in time to bigger and better things….

“We all sweated at that time out of fear,” elder Haralambos recounted,

that the tempting thoughts would find our deacon and fill his head with ideas, and that we would lose him forever. This was why, while we were very sorry for it (but it couldn’t have been done differently), we immediately gave the majestic and imposing Archbishop the necessary “lesson,” which made him reconsider, he was very offended, but completely clammed up. The blessed one based himself, it seems, on his title, authority, and on his fame, and figured that it would be very easy to accomplish, and right at his hand. This was also why he made his seductive offer so obviously, without planning, and in front of so many monks of Karyes, representatives and custodians of the other monasteries.

Hierodeacon Dionysius Firfiris with the deacons from Karyes, John and Ioasaph, and with Fr. Gabriel Magkavo, and Bishop Chrysostom of Rodostolou at the Protaton in 1978

At that time, the ever-memorable and similarly worthy official chanters of the Great Church of Christ, the Archon First Chanter Constantine Pringos and Lambadarios Thrasyvoulos Stanitsas, with their personal authority, led the choirs of the patriarchal church of St. George, and with their vocal and other talents made the patriarchal services and Divine Liturgies even more full of light. The faithful of Constantinople often “lost it,” and found it difficult to decide what they should be more amazed by: the nobility of style and the authoritative execution of the First Chanter or the voice of sheer beauty, and the limpid expression from the mouth of the Second Chanter.

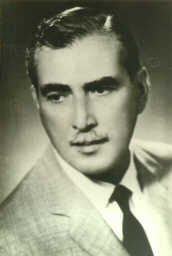

Thrasyvoulos Stanitsas

During the years of our studies in Halki, we had the good fortune and many opportunities to enjoy the chanting of Stanitsas during the height of his career. This was the time that he took over from the ever-memorable Pringos who, due to age and sickness, left for Athens. Stanitsas took over as First Chanter, and he ascended in all “modesty,” though in reality he desired it very much and everything fell into place for him. The truth was, though, that no one was bold enough, or able, to contain him. Even Patriarch Athenagoras, who caused his entire court to shake, overlooked his many peccadilloes, and avoided watching him and trying to make him shape up, because he feared losing him.

However, despite the arguments that he scandalized and stoked the dislike of the Turks, it was because he was noticed by the Turkish police and other authorities, as an official in the world of the Ecumenical Patriarchate and as the pride of the circles of Greeks in Turkey that, so as to hurt these groups, the Turkish authorities found ways to ensure his deportation.

So, chased away and highly tested, the Archon Stanitsas found himself in Athens, and was quickly picked up to be the chanter at the church of St. Demetrius in Ambelokipi, where he chanted for years, was admired, and became widely famous.

When Stanitsas came into his own in Constantinople, he would occasionally slip away secretly with a group of friends, reappearing at the panoramic center of the Prince Islands, where he would honor the place with his vocal talent. The neighborhoods would shut down as the locals abandoned their customers to quickly run to surround him so as to listen from closer in, amazed and speechless as long as the hymns continued, and then they would break into unceasing clapping. We Athonite monks also managed to go to the Phanar nearly every Sunday and whenever else possible, for the sole purpose of hearing his chanting. We enjoyed his gift, and learned whatever we could from hearing him.

We also found ourselves at a patriarchal service for a great feast, with a Divine Liturgy served by the bishops of the Holy Synod. We managed to get into the reception that followed, when we became eyewitnesses of the crowd of local Greeks who with great passion pushed, not only to kiss the right hand of the Patriarch, but also to shake the hand of Stanitsas, and to praise him vigorously.

Afterwards, when the people had left only we remained along with those in the patriarchal court, and a few bishops, among whom was the blessed Metropolitan Maximus of Sardeon, who stood out from the crowd. We listened to them praising the hero of the day. That was when Metropolitan Maximus, who was always positive and incredibly polite, so as to make it clear that he noticed our presence, and desiring to show honor towards the Athonite monastic habit, drew us into the conversation. He then asked directly if we agreed that the one being praised was the greatest chanter in Constantinople and within all of Orthodoxy.

We felt hedged in and in a difficult spot, but we had to say something, since we could not do otherwise. So, with respect and reserve, but also with the honesty and directness common to Athonite monks, we said that which we believed in our hearts, and held to be true, “Among those within Constantinople, most definitely, your Eminence. Among those throughout the rest of Orthodoxy, perhaps; but not among those on the Holy Mountain.”

The Metropolitan appeared to be taken by surprise, and all of the others murmured and became clearly sullen. Because we did not agree with their opinion, we felt the need to provide further explanation and to add, “It makes sense that you would think the way that you do, and to so strongly support your position, but this is because you haven’t had the chance to hear our Deacon Dionysius.”

Not much time had passed from that encounter (in 1960, if I remember correctly), when Deacon Dionysius, along with his very close friend (and also beloved to us) the sweet-voiced Deacon John, undertook a pilgrimage to Constantinople first, and then to Jerusalem. They were given hospitality for two days at the Ecumenical Patriarchate. While there, they would naturally go to the patriarchal church to participate in the brief mid-week services only attended by those within. We went to see them while they were there. They told us that, when they noticed that there was a need for chanters, they approached the chanter’s stand and chanted the responses for the priest.

We learned, however, that those present in the services were very moved by what they heard, and that some of those had been there during the conversation with Metropolitan Maximus, and who, on remembering what we had stated, said, “The monks were probably right.”

Fr. Dionysius passed his entire life in Karyes and, in particular, in the Hermitage of the Prophet Elias, just about a hundred meters from the church of the Protaton and from the enthroned miracle-working icon of the Axion Estin

Cherubikon, first tone. Fr. Dionysius Firfiris singing:

%%