A Holy Nation

4 July 2015“But you are a chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation, God’s own people, that you may declare the wonderful deeds of him who called you out of darkness into his marvellous light. Once you were no people but now you are God’s people; once you had not received mercy but now you have received mercy.” 1 Peter 2:9-10

Every year on July 4, our nation celebrates its independence from Great Britain, won through sacrifice and years of struggle and war. In more than two hundred years since the formation of the United States of America, our celebration has also come to be about much more: especially our American ideals of freedom, including freedom of speech, freedom of religion, freedom of the press, and above all, the freedom to be self-determining and to form local governments to meet the needs of the people.

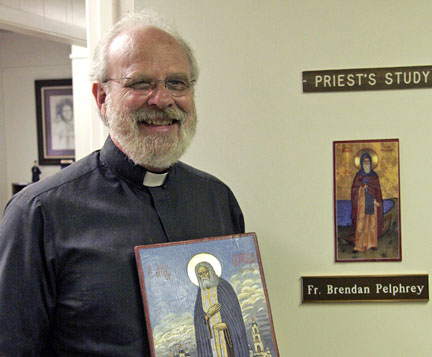

Fr. Brendan Pelphrey

It is interesting to reflect how we, as Orthodox Christians in America, understand our religious liberty and the relationship between our Orthodox Church, our government, and our American culture. Orthodox Christians are, of course, a tiny minority in the United States: all Orthodox Christians, of all the Jurisdictions, amount to perhaps only one percent of the population. This makes the Church in America very different from what it is in some parts of the world.

In some countries, it is regarded that nearly all the people are “Orthodox”—and therefore, that in some sense the nation itself is “Orthodox.” Here there may be little or no separation between Church and state, as was the case historically in the Byzantine Empire or in Czarist Russia. Sometimes the leadership in the government and the leadership in the Church are the same, as happened briefly in Cyprus only a generation ago. But the situation in America is obviously very different.

Not only are we an ethnically-diverse nation—with a history embracing many language-groups, religions and points of origin (not to mention the numerous indigenous cultures that were dominated or displaced here)—but the structure of our government guarantees that we can never be an “Orthodox” nation. The Constitution of the United States requires a separation between Church and State, with the provision that Congress shall pass no law for the establishment of religion.

Historically, this provision of the Constitution has been interpreted to mean that our elected government cannot establish a particular church as the “national” church, as had been the case in England. The wars between Protestants and Catholics in Britain—and indeed, all of Europe after the Protestant Reformation—were no doubt in the minds of the Founding Fathers. For centuries, kings and queens tried to enforce one religious group over another at the point of sword and cannon. The Founding Fathers did not want to see sectarian violence engulf the new United States in the way that it has more recently engulfed, say, Kosovo, Croatia, Iraq or the other states of the Middle East.

The “Establishment clause” also meant that our government could not force anyone to join one particular church group as over against another. Probably the designers of the Constitution had in mind the various Protestant sects, as opposed to the Roman Catholic Church; or, minimally, Judaism. They most surely did not envision Asian religions, Islam, Wicca, or Atheism as having a strong presence in the new United States—although they must have known that from the beginning, some of the early colonies did attempt to silence, censure or expel “free-thinkers” who did not care to belong to any particular religious group at all. Thus the founders of our nation provided for the freedom to join or not to join any religious group, as we individually choose.

Today, however, the “establishment clause” has been interpreted very differently. For many, it seems to mean that there should be no public expression of religious faith at all. Usually this means Christian faith in particular. Teachers have been censured or fired for wearing a cross. Students have been expelled or punished for bringing a Bible to school. City governments have been sued for displaying a crèche at Christmas. Businesses have been vandalized for having an inflatable Santa Claus outdoors. Home-owners have been taken to court for putting up Christmas lights. Increasingly, in our country the idea of “freedom of religion” is being replaced by the idea of “freedom from religion.”

Orthodox immigrants to America may be especially sensitive to the idea of enforced secularism. Not long ago in Turkey, Greeks and Armenians experienced genocide, first under Islam but then under a so-called “secular” government. But even where there is supposed to be religious liberty—in Great Britain and across Europe, for example—Christians are becoming a minority group who are increasingly not tolerated in the name of “tolerance.”

All this raises the question how Orthodoxy in America will look in the future. Orthodox Christians proudly wear a baptismal cross. Will it one day be forbidden in America, so as not to “offend” unbelievers or followers of radically-intolerant faiths? Will we be able to preserve our faith and way of life?

This raises the question how we understand ourselves as American Orthodox. Many Orthodox Christians in America today want to see a self-ruling, or autonomous, American Orthodox Church. Others, however have consistently referred to Orthodox churches in America as “diaspora”—not an American Church, but a collection of missions sent out from “mother” churches overseas.

When American converts to Orthodoxy hear the language of “diaspora,” it can seem very strange. Those of us who were born in this country may not feel like “diaspora” at all. We are simply Americans: part of the One, Holy, Catholic and Apostolic Church worldwide, many of us converts to the Orthodox faith. More and more Orthodox churches are using English as the predominant language of the Liturgy—just as Orthodox churches throughout history have used the language of the local people. But even where that is not the case, increasingly we realize that the language, customs and culture of the “mother churches”—our parents, grandparents, and great-grandparents—are in danger of being lost. Surely, part of our task is to preserve this heritage.

The issue of “American Orthodoxy” has been much debated in recent years. However, rather than debating whether there should be, or can be, a truly “American” Orthodox Church, it might be helpful to think about what the Apostles taught with regard to faith and government. This can be a model for us today.

The Roman Empire during the Apostolic Age was of course pagan, with a minority of religious Jews living as an occupied people. In the Apostolic era, Romans viewed Christian faith as a dangerous superstition (superstitio), rather than as a true religion (religio). Indeed, Christians were often charged with being “atheists.” Nevertheless, even during the fierce persecution of the primitive Church and shortly before his own martyrdom, the Apostle Paul called upon Christians to pray for the Roman emperor and for all those in government, so that the nation might have peace. Our churches continue this practice today in the Divine Liturgy.

The Apostle Peter went further, to say that as followers of Christ we are a “chosen race, a royal priesthood, a holy nation (ethnos)” (1 Peter 2:9). He was fully aware that the Church did not, and could not, constitute the government. However, Pentecost meant that people of all languages and ethnic backgrounds, from every part of the known world, were joined together into the one Body of Christ. So while Christians would respect and obey their government, even a hostile one, they would be primarily citizens of Paradise, a multi-ethnic Heavenly Kingdom ruled by Christ.

Because we Orthodox in America are a small minority, our non-Orthodox friends may say that we are strange or peculiar. We can respond that we are indeed a “peculiar people” (1 Peter 2:9, in the translation of the Authorized Version of the New Testament). However, we are also American. At the same time, we are also diaspora. Like the rest of America, our Orthodox churches originally came here from somewhere else. Nevertheless, we have the power to transform the American culture in a way that no other interest group, or government agency, or individual, can.

Just as the Holy Spirit is given to us individually so that we might grow into the likeness of Christ, so the Holy Spirit can, and does, enter into every culture where there is the Church. Where death may be at work in our society, nevertheless life is at work through our presence in America. In this sense our American culture can be “baptized.” This happens gradually and quietly, as we Orthodox participate in American life.

Jesus said that we are like leaven in a loaf, or like salt. Leaven and salt are virtually invisible, but they transform and preserve. Similarly, the presence of Orthodoxy in America brings change to America, giving life and preserving and protecting what is here. We do not need to be the ruling party; the Church does not need to be the government; we do not need to constitute a majority. Rather, we simply need to be a presence—the presence of Christ in America.

Source: myocn.net