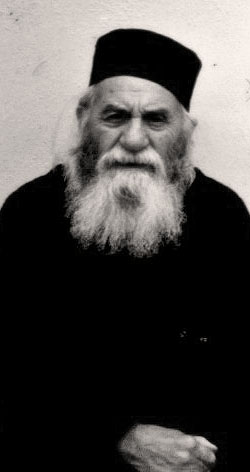

Father Zacharias Dionysiates (1909-2000)

12 October 2015Over the long course of my monastic life (1964-2015) I’ve known a host of monks who are now in the Church of the First-Born in the heavens. Of these a good number quitted the outside world in the flower of their youth, others in middle age and yet others in their declining years. I’ve known holy men from all of these ages. Some of them, indeed, had previously been married. The life they led earlier is of no importance, what matters is the life they led after they’d heard and submitted to the call from heaven. Saint Peter was married, but once he’d heard the call he followed the sound of the voice of Christ, his Teacher, to such an extent that he felt able to say to the Savior: ‘Behold, we have left everything to follow you’ (Matth. 19, 27). But if we examine their Christian way of life before they became monks, we see that even when they were still in the outside world they practiced the virtues and observed the Gospel commandments. Saints Xenofon and Maria became monastics at an advanced age, yet outstripped in virtue their children who’d been tonsured at a young age. Saint Symeon, the founder of the Holy Monastery of Hilandar, even though he was already elderly when he followed his son Savvas into the monastic life, is still known as ‘myrrh-exuding’, because after his death his tomb smelled of fragrant myrrh and, to this day, performs countless miracles.

Recently quite a number of monks have gone to the Holy and Great Monastery of Vatopaidi from having been married in the world and they have left an indelible mark with their exemplary obedience. Among these were the late fathers Filaretos, Ioakeim, Ermolaios, Tryfon and others, which the Monastery would do well to present in greater depth as an example to the younger brothers.

Recently quite a number of monks have gone to the Holy and Great Monastery of Vatopaidi from having been married in the world and they have left an indelible mark with their exemplary obedience. Among these were the late fathers Filaretos, Ioakeim, Ermolaios, Tryfon and others, which the Monastery would do well to present in greater depth as an example to the younger brothers.

Another rose that blossomed late in the desert was a monk in our own Holy Monastery of Dionysiou, a man who, even though he was already old when he renounced the world, still managed to outdo in virtue many of those who had been tonsured young.

As a layman, this monk was known as Yorgos Bousoulengas, but when he adopted the monastic habit he was renamed Zacharias.

Yorgos came from Veria and was born to devout parents in 1909. From childhood he was hard-working and obedient to his parents. In fact, in order to earn a living and to help his parents financially, he became one of the best cheese-makers of his day.

In 1929-30 he was invited to Turkey, to make cheese on a large farm which had thousands of sheep and goats. As a master of his craft, Yorgos made such wonderful cheese that it became famous everywhere. The Aga saw this, thought a while and then one day said to his wife: ‘We won’t find a better husband for our daughter. Agreed? Agreed”. So he summoned his employee and said, ‘Well, Yorgos, do you see how enormous this farm is, with its animals, trees and houses? It’ll all be yours. All I have is an only daughter. I’ll marry the two of you off and it’ll all be yours’. How did Yorgos react? Without a second thought, he answered: ‘Sir, never mind the farm. Even if you give me the whole world I won’t change my faith’. The Turk insisted, but so did Yorgos. In the end the Turk became frustrated and picked up a big sword and threatened him, saying: ‘Either you accept my daughter or I’ll cut your head off’. But the brave confessor, who was quite prepared to suffer martyrdom, bowed his neck. ‘There you are, sir, cut it off’. Then his master did an about-face and set the scimitar aside. He embraced him and said, in admiration: ‘Well, done, young man. You’re really something, Yorgos, that you’d bare your neck for your faith’. And from then on the Aga held him in special admiration, because he realized what an honorable person he was.

But that wasn’t the end of it. He hadn’t gone to Turkey alone at that time. There was a group of young me who emigrated for economic reasons. They would meet up in the evenings to spend some time together. As they were talking, Yorgos told them what occurred. And what do you think happened? That they congratulated him? On the contrary, they all called him an idiot. ‘Stupid. In one day you could have become a millionaire and you chose death? Are you crazy or what?’

But Yorgos never regretted his decision. He’d rather become a ‘fool for Christ’ and a potential martyr than be rich and forsworn.

After Yorgos had put in 2-3 years of honest work abroad, he came back to Greece. It wasn’t long before he met a modest Greek girl, Despina and they married in 1937. They lived an exemplary married life and brought four children into the world. One of these, Nikolaos, decided at the age of 22 to follow the monastic way of life and entered the brotherhood of my late Elder, Papa Haralambos, while we were still at the large kelli of Bourazeri, which belongs to Hilandar. As a monk he had his name changed to Panteleïmon. He was soon promoted to the status of priest-monk and he continues, to this day, to be an adornment of the Monastery of Dionysiou, to which our brotherhood was invited because they had very few monks of their own left.

Yorgos faced great examinations as a layman in World War II. He was conscripted in 1940 with all the other young men and fought in the front line in Albania. He reminisced and told us: ‘We had 16 attacks from the Italians on the front line. The bullets whistled past us, often going through our shirts without touching us. That’s when we saw the protection of Christ and His Mother clearly in front of us. Unfortunately, it wasn’t enough that our lives were in danger on a daily basis. There were also soldiers whose minds were still bent on debauchery and blasphemy. They’d leave the front and head off to the dens of iniquity. We saw it with our own eyes; it was as if the bullets were seeking them out. All the casualties we had were people like that. I lived in the fear of God, with prayer as my main weapon. This was hardly likely to go unnoticed by the other soldiers. When we were being bombarded and bullets were flying around me, the others clung to me. I said: ‘What are you doing? Let me go’. They replied: ‘You’re righteous. You’ll get us out of here as well’.

The boundaries of Greece briefly extended into Northern Epirus, but it was not long before the iron-clad tanks of the Germans descended and Greece was once more under the yoke of the Germans until 1944. Of necessity, the Army was disbanded and Yorgos returned to his family, with whom he spent the following years of great trial for the Greek nation.

In 1955-6, Yorgos was invited to Cyprus, not only to work but to pass on his technical skill as a cheese-maker. In Cyprus, the main type of cheese that’s produced is haloumi. Yorgos remembered the liberation struggle of EOKA in those years. How many times the British made raids into the cheese factory and turned everything upside down in an attempt to find arms. They’d take suspects, mostly people who were innocent, and put them in prison, where they were beaten and then confined to house arrest. All of this was indelibly stamped on Yorgos’ memory.

But here, too, he was fated to undergo an examination similar to the one in Turkey. When his boss saw that he was such a master of his craft and that business was picking up, he offered his daughter in marriage. But again Yorgos rejected the idea out of hand. ‘But instead of being an employee, you’ll be the boss. And you won’t accept?’ Very politely, Yorgos explained: ‘Thank you, but I’m already married with children and I’m not about to go back on that’. So he passed these trials with flying colours, both as a cheese-maker but also, and more importantly, as regards his virtue. And so he was able to return to his family.

Yorgos endured harsh trials throughout his life. Another one of these was when his dear wife, Despina, fell ill with a severe form of diabetes. Her husband shared her sorrows, the chief of which was the amputation of both her legs in 1984. From then on, until her departure from this life in 1991, she was in a wheelchair, and Yorgos gladly saw to all her needs.

Sometimes he’d leave one of his children in charge and come to the Holy Mountain, where the desire took root in his heart that, after the demise of his wife, he would become a monk. Despina survived without complaint until 1991, when the Lord called her to rest.

Yorgos felt a mixture of sorrow and joy, because he was now free to fulfil his desire. But even at his age he wasn’t free from of the machinations of the cunning enemy. No sooner had Despina’s forty days passed when a neighbour paid him a visit. Why? To make a match for him: ‘I know a woman, who’s got millions in the bank and she wants to marry you. You’ll live a charmed life just on the interest’. Yorgos replied: ‘Thank you, but I won’t remarry’. She insisted: ‘Don’t be a fool. You’ll be so happy’. Once again, Yorgos rejected the idea without further discussion.

On the Holy Mountain (1993-2000)

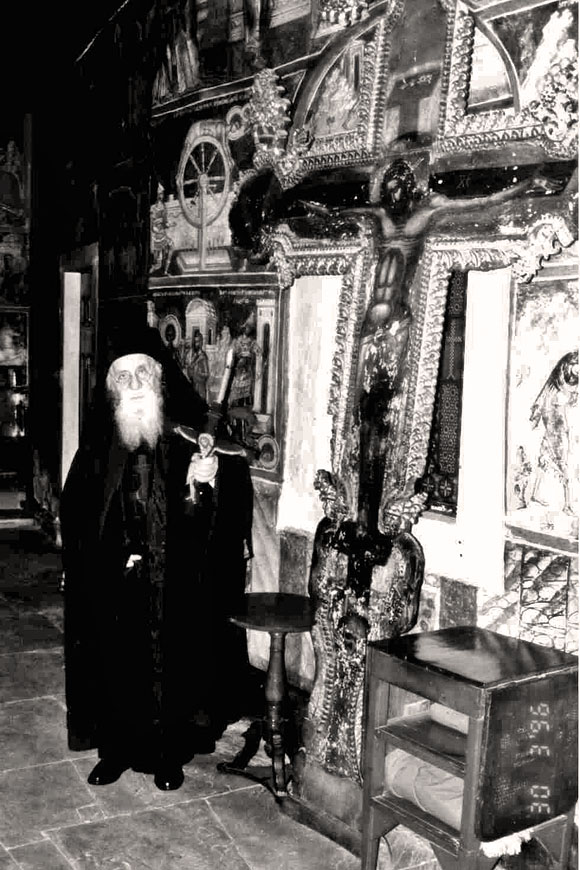

Once Yorgos had settled the family matters that had arisen after his widowhood, he arrived, like a thirsty hart, even at the eleventh hour, at the Monastery of Dionysiou, where he was with his son, the priest-monk Panteleïmon. His spiritual father was our late Elder, Haralambos. Even though he’d already retired from the position of Abbot, Elder Haralambos, with the consent of the new Abbot, tonsured Yorgos as a monk of the Great Habit the following year, giving him the name of Zacharias, in honour of the father of the Monastery’s patron saint, the Honourable Forerunner. The atmosphere at his tonsure was most moving, and from then on he became an exemplary monk. He observed the rule he’d been given, he was first at the services, he was as obedient as his bodily strength permitted and in general encouraged us younger monks by the way he lived. Mostly he stood out for his virtues of humility, love, meekness, patience and so on. No-one ever saw him angry or misbehaving. When he was asked to do something which went against his conscience, he’d reply: ‘No, I can’t’ or ‘No, I don’t want to’.

Apart from everything else he was endowed with blessed simplicity. He would often sit outside the main gate of the Monastery and lots of visitors, seeing a little old elder, would come to him for advice. He never pretended to be an old ascetic, though, and simply told them: ‘I’ve only been a monk here for a few years, but I’ve got a son who’s been here 35. He’s a spiritual father, as well, so you should go to him’. And yet, with his simple words he still helped a great number of visitors, because what he said was the fruit of experience.

Just as it was no accident that the martyrs were involved in persecutions and were killed, but rather that it happened because they’d lived an exemplary life until then and were crowned with martyrdom as the culmination of their lives, so our late brother Zacharias, who had led an exemplary married life, was crowned with the angelic habit and numbered among the ranks of the monastics.

He lived until 2000. Then the Lord called him to the heavenly tabernacles which are ‘the abode of the rejoicing’. May his memory be eternal.