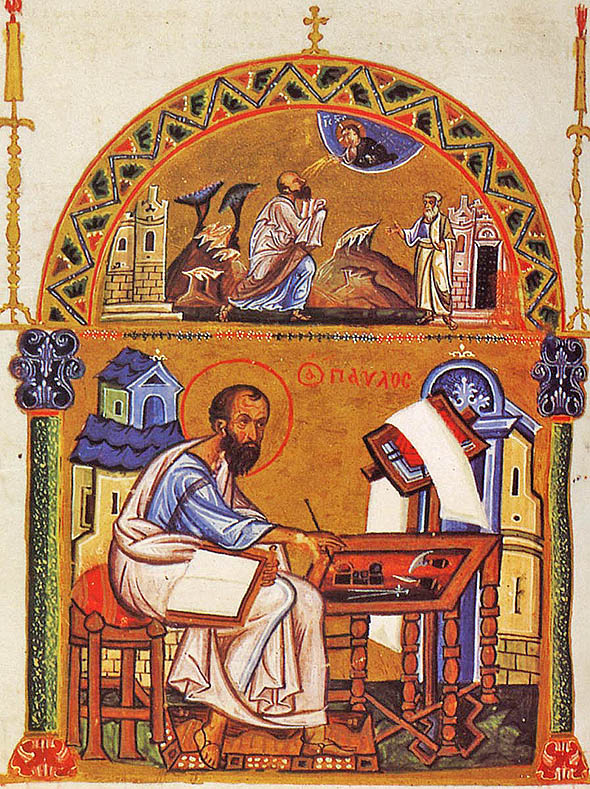

The Apostle Paul: Incorporeal, even though he had a Body – 1

30 June 2016More than all other people, it’s Paul who shows us what we are, how noble our nature is and what measure of virtue we’re able to achieve. And now he arises from the place he has arrived at and, in a clear voice, to all those who condemn our nature, he defends us on the Lord’s behalf, urging us towards virtue, stopping the shameless mouths of those who blaspheme and proving that there’s very little difference between us and the angels, if we but guard ourselves.

Without having a different nature, without receiving a different soul, nor living in another world, but, having been brought up on the same land and place, with the same laws and customs, he surpassed all the people who’ve ever lived since our race was founded. Where are those people who say that virtue’s difficult and evil’s easy? Because Paul rejects this, saying: ‘For this slight, momentary affliction is preparing us for an eternal weight of glory beyond all measure.’ And if such afflictions are slight, how much more so are our pleasures.

This is not the only admirable thing about him- that, because he was so greatly disposed he didn’t suffer from his efforts at gaining virtue- but that he also exercised virtue without reward. We, of course, don’t put up with pains for the sake of virtue even if there are rewards. He, on the other hand, sought it without any prizes, and easily overcame anything that was considered a hindrance to it. And he never invoked the weakness of the body, the difficulties of his circumstances, the tyranny of nature, nor anything else as an excuse. Even though he’d taken on more responsibility than generals and all the kings of the earth, he was on top of things every single day and, although the dangers increased, he still displayed youthful enthusiasm. This is why he declared: ‘Forgetting what lies behind and straining forward to what lies ahead’. And while he was awaiting death, he invited others to enjoy it with him: ‘Rejoice and be glad for me’. Even though he was threatened by dangers and suffered insults and every form of dishonor, he still rejoiced, writing to the Corinthians: ‘Therefore I am content with weaknesses, insults, persecutions’. He called these the armour of righteousness, showing that he derived great benefits even from them and that he was protected on all sides from his enemies. And although they tormented him everywhere, despised him, defamed him, he went from strength to strength and proudly planted trophies all over the earth, thanking God: ‘Thanks be to God who always leads us in triumphal procession’.

And he sought maltreatment and insult about his preaching more than we seek honour, and death more than we seek life, and poverty more than we seek riches, and pains more than others seek comforts- not just a little more but much more- and sorrow more than others seek joy and to pray for his enemies more than others cursed them. And he overturned the order of things, or rather we’ve reversed them. What he did was keep that order as God had ordained it. Because what we said above [the positive things] are in accordance with nature, but the rest [the negative], are against it. The proof of this? That Paul, who was a human being, observed the former rather than the latter. The only thing that was dreadful for him, and which he avoided, was conflict with God- nothing else. Just as, of course, nothing else was desirable for him, other than pleasing God. And I’m saying nothing about the present or the future. And don’t tell me about cities, nations, kings, armies, money, satrapies and dynasties, because he thought them less than a spider’s web. But just think about what’s in the heavens and then you’ll understand the powerful love he had for Christ. Because this was a filter for him, Paul admired neither the status of the angels, of the archangels or anything else.

He had within him the greatest thing of all- love of Christ. And with this, he considered himself the most fortunate of men. Without it, he had no desire to become one of the dominions, the principalities or powers, but with this love he desired to be among the least and the lost, rather than among the first and foremost. For him, there was only one hell: to lose that love. That was Gehenna for Paul, that was punishment, that was infinite evil, just as delight was to achieve that love. That was his life, his world, his angel, his present, his future- kingdom, promise and wealth untold. Anything that didn’t lead to this he thought neither unpleasant nor pleasant. In the same way that he wrote off all visible things, as if they were sodden grass. The tyrants and the cities that foamed with rage against him, seemed like mosquitoes, while the torments and punishments were like so many childish games, which he suffered for Christ.

He accepted them with joy and was prouder of his chains than Nero was when he had the royal diadem on his head. He spent his time in prison as if he were in heaven and accepted the blows and whippings more gladly than others seized prizes. He loved the pains no less than the trophies, because for him that’s what they were. This is why he called them grace. But note this well. It was a prize to die and be with Christ, but the contest was in staying alive. Yet he preferred the latter to the former, since he thought it was more necessary for him. Being separated from Christ was a struggle and an effort, whereas being with Him was the prize. But, for the sake of Christ, he preferred the struggle.

You might say that all of that was a pleasure for him, because it was for Christ’s sake. I also say that: that what for us would be a cause of sorrow brought him great satisfaction. So why do I talk about the dangers and other tribulations? Because he was genuinely in a constant state of grief. This is why he said: ‘Who is sick and I’m not sick, who is made to stumble and I’m not indignant?’ But you might say that he even had sorrow as a satisfaction. Those who lose their children and are allowed to mourn, are comforted; but when that’s forbidden to them they’re distressed. Nobody’s ever mourned their own woes as much as he did those of other people. How do you think he behaved when, given that the Jews aren’t saved, he prayed to fall from heavenly glory so that they might be? It’s obvious that, if they weren’t going to be saved, this was much worse for him. If it hadn’t been, he wouldn’t have asked for this. But he thought it a lighter burden and one that had greater consolation. It wasn’t just that he wanted it, but he cried aloud, saying: ‘I have great sorrow and unceasing anguish in my heart’.

Second part, here: http://pemptousia.com/?p=27313