Communion & Division – The Structure of Knowledge: The Web of Belief

18 October 2016A second brand of philosophy against which divine revelation should put us on guard is what goes by the name “web of belief,” in which all knowledge of the truth is interpreted as, and thus, reduced to a mere corres-pondence between the mind and reality. This appeal to a “web of belief,” an expression I believe we owe to Willard Van Orman Quine (1908–2000), recognizes only a noetic correspondence with facts, no “truths of being.” The only objects that man can know are—to borrow the expression of Joe Friday—“just the facts, ma’am.” The only basis of truth is the mind’s congruity with fact.

Or, to employ the distinction and terminology of Gottfried Leibniz, this “web of belief” philosophy asserts that the mind can discover truths of existence, but it cannot perceive truths of being. It can recognize contingent facts, but it cannot directly discern their internal meaning, because the mind has no direct access to Logos. Man’s mind can recognize existence, but it cannot know essence.

In theological terms, this means that I can discover that Christ died, but I cannot know that he died to redeem me from my sins. I may even prove that Christ arose again from the dead, but I cannot know that he rose again for my justification. According to the “web of belief,” such matters as atonement and justification remain as external to me as the historical events that cause them. Atonement and justification are no longer internally accessible, and all truths of revelation are reduced to propositions that remain external to my assent. Revelation is no longer related to the structure of being.

This theory is called the “propositional” view of divine revelation, in which both the historical facts and the meaning of those facts remain external to the believer. According to this interpretation, God has revealed certain propositional statements to which the mind must assent, on purely external authority, whether that authority be the prophetic word inerrantly inscribed in Holy Scripture or the ecclesiastical word defined by an infallible magisterium. It is surely significant that many of those who hold such a view of revelation also hold to a theory of external justification and merely forensic atonement.

I submit, however, that such a perspective is not that of Holy Scripture. God’s revelation to us in his Son and Holy Spirit asserts man’s capacity for real knowledge, as distinct from mere notional information and correct opinion. If our theological knowledge in faith is real knowledge and not simply conceptual correspondence—if St. Thomas Aquinas was right when he said, “actus credentis non terminatur ad enuntiabile sed ad rem”; “the act of the believer does not terminate in the proposition but in the reality”—if this is so, then how much more is it so of lesser matters. If in faith man’s mind has been transformed and elevated by the Holy Spirit to know God himself, there is no reason to deny that man can know other things in themselves.

To know the truth, then, is really to know the truth, not simply to hold to certain ideas that “correspond to” the truth. To know the truth is an act formally different from holding opinions and beliefs that happen to be correct. To know the truth is to have one’s mind shaped by real form, rei forma; it is something quite other than venturing an accurate and well-informed guess about reality. Real knowledge, therefore, is not some kind of inwardly symmetric and coherent web of basic beliefs that “correspond” to reality in varying degrees of probability. To know the truth is to have one’s mind contoured by the shape of being. That which makes a res to be a res is its forma, its morphe, and to know that res is to have one’s mind shaped by that same form. Thus, real knowledge, the knowledge of reality, is not correspondence but communion. To know is to become one with the truth, co-gnosco.

In this matter how have we fallen so far from convictions that were obvious to our distant ancestors in the faith? I submit that the villain here is Immanuel Kant, for whom thought consisted in the mental organization of sense experience. According to Kant no “thing in itself,” no res in se, no Ding an sich can be known. I beg to make my own the following analysis of Kantian philosophy by Norman L. Geisler:

Lost in [Kant’s] model of the knowing process was the ability to know reality. If Kant was right, we know how we know, but we no longer really know. . . . [T]he net epistemological gain was the ultimate ontological loss. . . . What is left is the thing-to-me, which is appearance but not reality. Thus, Kant’s view ends in epistemological agnosticism.

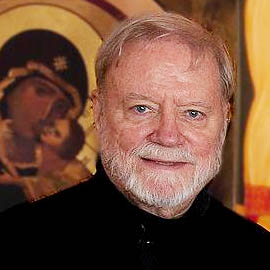

Patrick Henry Reardon is pastor of All Saints Antiochian Orthodox Church

in Chicago, Illinois.

He is the author of Christ in the Psalms, Christ in His Saints, and The Trial of Job.

He is a senior editor of Touchstone.