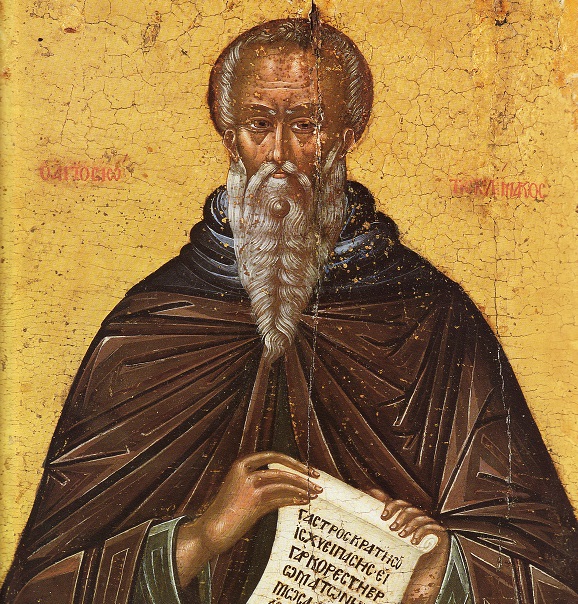

St John of the Ladder – Part IΙ

29 March 2017Still, whether incompatible or not with the modern sense of the self and of identity, The Ladder of Divine Ascent remains what it has long been, a text that had a profound influence, lasting many centuries, in the monastic centers of the Greek-speaking world. As such it deserves at least a hearing, if only to ensure that the awareness of the Christian past is not impoverished…

Hardly anything is known of the author, and the most reliable information about him can be summarized in the statement that he lived in the second half of the sixth century, survived into the seventh, passed forty years of solitude at a place called Tholas; that he became abbot of the great monastery of Mount Sinai and that he composed there the present text. The Ladder was written for a particular group, the abbot and community of a monastic settlement at Raithu on the Gulf of Suez. It was put together for a restricted audience and to satisfy an urgent request for a detailed analysis of the special problems, needs, and requirements of monastic life. John Climacus was not immediately concerned to reach out to the general mass of believers; and if, eventually, the Ladder became a classic, spreading its effects through all of Eastern Christendom, the principal reason lay in its continuing impact on those who had committed themselves to a disciplined observance of an ascetic way as far removed as possible from daily concerns…

John Climacus is concerned not so much with the outward trappings of monasticism as with its vital content. To him the monk is a believer who has undertaken to enter prayerfully into unceasing communion with God, and this in the form of a commitment not only to turn from the self and world but to bring into being in the context of his own person as many of the virtues as possible. He does not act in conformity with virtues of one kind or another. Somehow, from within the boundaries of his own presence, he emerges to be humility, to be gentleness, to be sin abhorred, to be faith and hope and, above all else, to be love…

Influential texts, of course, have a life and season of their own. They supply the dominant themes of an era, acquire eventually the status of the honorably mentioned and the unread, emerge once again to promote undreamed-of perceptions, and slip, perhaps forever, out of sight and out of reckoning. But in a time of rapid change, such as today, even the capacity to ponder or to remember can be so blunted that not only will an individual work sink from view, but the very realm it opened up, the vein it disclosed, will also disappear, leaving men with an impoverished vision and a diminished grasp of the available images and ideals from which to construct for themselves a worthwhile sense of meaning and purpose.

To lose an awareness of the choices on offer, to be locked without respite into a single, all-pervasive bias, is a disaster. This much at least is clear amid the unfinished history of the twentieth century, with its countless grim examples of unsheathed bigotry, rampant prejudice, and dreadful unreason. But in the meantime there is still the influential text, like some shining life, presenting as does The Ladder of Divine Ascent one of the many opportunities to confront a view of being and of man. And if the fruit of such a confrontation is a researched “No”, or a reasoned acquiescence, then indeed the sum of human enrichment can confidently be held to have been augmented.

Colm Luibheid, Preface to John Climacus, The Ladder of Divine Ascent, Paulist Press 1982.