Exactitude and Dispensation through an Overall Consideration of the Sacred Canons

16 December 2018The sacred canons are the practical expression of the dogma, the faith of the Church, and can be viewed as such, because otherwise dogma would be banished to the sphere of the metaphysical, of the inaccessible, beyond participation, in which case the uncreated energies would remain dormant. But dogma is not there merely to be believed and nothing more, it’s supposed to be lived, to be expressed through words and deeds, theoretically and practically, ‘believing in love and loving in truth’. So a rational consideration of the canons as a practical expression of dogma is a matter of faith and acceptance on the part of those who belong to the Orthodox Church. The canons aren’t removed from dogma, nor are they close to it- even very close- but rather they co-exist, they inform each other as a single sacred value which reveals and leads to the truth and which provides the water of eternal life.

Another issue connected with the sacred canons is viewing or separating them into dogmatic and administrative, obligatory and optional and so on. If we bear in mind that the life, the nature and the communion of the Holy Trinity is ‘simple’, as is the life of the Church in Christ and the Holy Spirit, without syntheses, antitheses and differentiations (as is true of anything regarding God and His Church), then why should we see the canons in terms of complexity, at times expanding and at others contracting them, interpreting them at times with exactitude and at others with elasticity.

The supporters of both positions have powerful arguments and promote their views passionately, but, in each case, believe and accept that the aim of Holy Scripture, the canons and Tradition in general is ‘to know the One True God and Jesus Christ Whom He sent’. We may not step outside the lines drawn by the Apostles and the Fathers, nor can we depart from the safe path they trod, because any deviation from their course is unsafe and harmful, putting in doubt the salvation of our eternal soul.

If we accept dispensation, as this is generally understood in Church circles, who will interpret the ‘spirit’ of the canon, or, to put it differently, how should we remain faithful to a canon, respecting the letter? To one but not to another? What should be the tool or the criterion that would change the smooth path already drawn and sanctified by the holy Fathers? And if this occurs by invoking ‘the will of the legislator’, who’s to tell us what that will is, when it wasn’t only one person who established the canon(s) but a plurality, that is a Synod? What is the will of the supposed (imaginary) legislator in any given case involving many persons? Did the ‘legislator’ enter the mind of each member of the Synod and make sure that they were all of the same opinion?

The Fathers came to formulate the canon(s) animated by a variety of experiences, events, feelings and views, but, still, guided and inspired by the One Holy Spirit. They reached unanimity in their decisions regarding the pastoral care of the Church and the way of dealing with any bourgeoning problems that might affect it. So we can’t say what the ‘legislator’ wished to say, nor what the ‘spirit’ of the canon is, because we don’t know what each of the Fathers had in mind, far less so when a particular canon was confirmed or complemented by later Synods. In that case, we’d have to investigate the will of the first members and then the later ones, as regards what each of them meant in each instance. So we must be very careful when we say ‘This, or that, is what the Fathers meant’. What they wanted to say, they said precisely, in the sacred canons, which are invested with eternal authority, even if the implementation be temporarily suspended, through what we call dispensation, though this is not something that should generate euphoria.

If somebody gets gangrene, their survival involves the loss of a member of the body. The fact that the person is saved makes us happy, but we still can’t be enthusiastic about the loss of a limb.

For what else is greater than this? When the Lord Himself made use of dispensation and ‘bent down the heavens and descended’ of course this was extreme dispensation, extreme humility, extreme condescension, but does the fact that we ‘forced’ God to act in this way make us happy and proud? So how can we feel happy and joyful when we make use of dispensation? It should make us sad and make us keep our eyes trained on a return to order and exactitude.

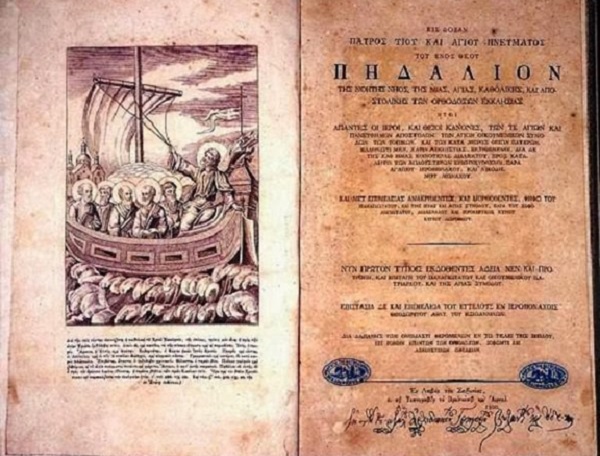

The authority of the sacred canons is invested with divine validity because they came about through the inspiration of the Holy Spirit Himself. They’re His own work. So the canons and the Holy Scriptures constitute the two lungs of the Church, which Christians ought not merely to respect and revere, but should also live and breathe.

Observance of the sacred canons isn’t optional, nor has it to do with a ‘reference point in the perfection towards which we are tending’. It’s obligatory and if we have to break it, this should always be in a state of repentance and confession, and we should hasten to return to orthodoxy and orthopraxy [right thinking and right action], though this should not be taken as meaning that these two, as lived or examined, are separate. Because, with the laxity that has crept into the spiritual life of Christians, the canons have been absorbed by dispensation and dispensation’s become the rule [canon], as it were a kind of ‘canonical Monophytism.

The sacred canons don’t ‘punish’ rather they ‘regulate’ any deviation from orthodoxy and orthopraxy. A sin isn’t forgiven, but ‘regulated’ in proper fashion, as envisaged by the canons.

In general, we might say that the Church (positively or negatively) has become ‘Biblical’: it judges Holy Scripture and Holy Scripture judges the Church, while both judge and are judged by the sacred canons, since Holy Scripture and the sacred canons were begotten by the Church. They’re judged by the Church and the Church is judged by both.