Respect for Others as a Restriction of Freedom

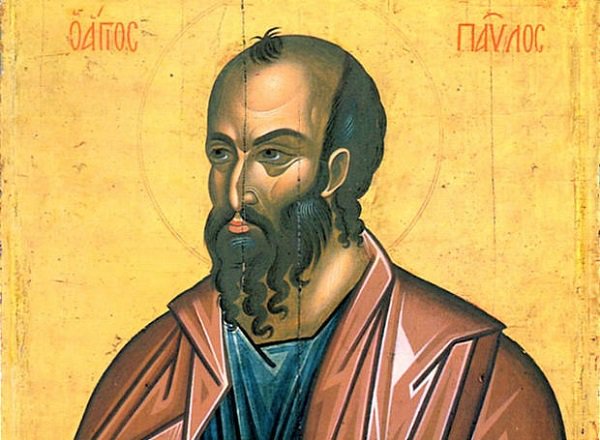

5 March 2019Saint Paul’s 1st Epistle to the Corinthians is the richest in terms of the number of issues he addresses. Among the many subjects the Corinthians asked him about was that of eating or not eating food offered to idols, that is the meat remaining after an animal had been sacrificed to the gods. Because there was usually so much of this meat, it was given to the butchers or distributed as food at the ‘idoleum’, the temple and its surrounding area. There were opportunities for this every day (festivals, fairs, weddings, funerals and so on), and the obvious social commitments on the part of Christians towards their fellow-citizens would have meant that they had to take part in such events.

In Corinth, there was a group of free-thinking Christians who believed- quite rightly- that the idols didn’t actually represent anything in the world and that there is only one God, as the epistle says just before today’s reading (1 Cor. 8, 4) and so they didn’t consider it to be a sin to take part in the idolaters’ banquets. It may be that the first sentence in the reading was a declaration on their part: ‘Food does not bring us near to God; we are no worse if we do not eat, and no better if we do’. As the outstanding Apostle of freedom, Saint Paul essentially accepts the claim of the Christians in Corinth for theological reasons. As their instructor, however, he sees the issues in broader terms and sets love as a bar and restriction on freedom. This is expressed as respecting the scruples of others. The love of which Paul speaks isn’t exhausted by a mere friendly feeling, manifested in a variety of psychological ways, but has a more profound theological content: it derives from the sacrificial love of Christ on the cross. This love of Christ’s, which was revealed on the cross, is the basis and source of love between all of us.

Of course, the problem of eating food sacrificed to idols no longer exists today, but Paul’s answer is still valid. Our freedom as Christians isn’t untrammelled and is restrained by love for others and respect for their principles. Paul is concerned that the knowledge and authority we have as Christians could have been a cause of scandal for others who had a weaker ‘conscience’ and who considered it a sin to eat the meat that had been sacrificed to the gods of the idolaters. Should they continue to eat meat sacrificed to idols in such a case, in the name of the freedom and the knowledge they had concerning the non-existence of idol gods? In 8.1, he already provides the answer: ‘But knowledge puffs up while love builds up’. With what he writes, the Apostle indicates that he wasn’t thinking about individual Christians, but of the community as a whole and of the reservations of some. In 10, 29, he states explicitly: ‘when I speak of conscience, I do not mean yours, but the conscience of others’. Even if it’s the result of our freedom in Christ, any action we commit as Christians which scandalizes the conscience of weaker believers is a blow to the redemptive work of Christ. When dealing with the same issue, he wrote to the Romans: ‘Let no food be a cause of spoiling God’s work’ (Rom. 14, 20). Both strong and weak Christians all belong to the same Body of Christ. Therefore any action directed against the reservations of other members of the body has repercussions on the Head of that Body. Paul repeats the word ‘brother’ four times in the reading, clearly wishing to stress the notion of community. Lack of respect for the conscience of others means disregard for the whole Body, and, in particular for the Head, Christ Himself. This is meaning of verse 12: ‘When you sin against them in this way and wound their weak conscience, you sin against Christ’. This is why Paul would rather sacrifice his freedom on the altar of love than have that freedom scandalize another member of the Church.

Finally, as an example of freedom through love and a cession of his rights, Paul mentions his own case in the last verses of the reading (9, 1-2). The reason was the Judaizers who accused him of not being an apostle. They spread it about in Corinth that he had no conscience and that he wasn’t a proper apostle of Christ, since he wouldn’t accept the material gifts of Christians. These were given in accordance with the principle that anyone who laboured for the Gospel was entitled to live on the gifts of those who heard the Gospel, as was also the case in the Old Testament. Paul attributes his cession of this right to the transcendence of freedom and ‘authority’ for the sake of love. Beyond the authority which he has as an apostle lies love and the seamless fulfilment of his task as an apostle.

Summarizing the above, we would note the following:

1. In and of themselves, foods are neutral. They can’t accompany us to the seat of the righteous Judge, either in our defence or to our detriment. There’s no advantage or disadvantage to be had from using them or abstaining from them. What is important is that they shouldn’t become a cause of scandal for others, since this would be an affront to Christ.

2. Our freedom as Christians is restricted by our love towards others. This constraint isn’t an abolition of freedom but a confirmation of it, because ceding our legitimate right in order to avoid shocking other members of the Body of Christ is, in essence, itself an act of freedom.

3. All actions on the part of Christians affect the whole of the Body of Christ, especially the Lord Himself, as its Head. If, in the name of our own freedom, we disregard the conscience of others, this undoes the work of Christ. ‘Building up’ others should be the aim and purpose of all our actions as Christians.