Some Thoughts on the Period of the Triodio

6 March 2019…Here is Paradise and Hell’s here, too (Greek folk song)

… as the shepherd separates the goats from the sheep (the Gospel)

There are many people, both in older times and now, who reject the metaphysical version of the continuation of our lives in a state of Paradise (perfect bliss) or of Hell (the agony of permanent and total loneliness). They therefore laugh at the folk-art engravings which depict Hell as a ‘pit’ of fire and bodily tortures and Paradise as a ‘garden’ with a freshly-mown lawn, full of beautiful flowers, where idle simpletons, replete with virtues, stroll around at their leisure. They claim that such notions are groundless and that therefore ‘Here is Paradise and Hell’s here, too’.

But let’s look at this in more detail

In chapter 25 of the Gospel according to Saint Matthew, Christ describes our relationship with God in three images.

In the first, introductory one (25, 1-13) He tells the well-known parable of the Ten Virgins, which addresses not only the subject of our theoretical longing for the encounter with the Bridegroom/Creator (they went out to meet Him) but also that of the actual preparation for this meeting (oil in the vessels). It’s not enough to wait; you have to have what’s necessary for this meeting so that you don’t prove to be half-witted (the foolish virgins). So the initial condition is that you should be in a state of readiness for any unexpected invitation or meeting.

The second image (25, 14-30) describes the mystery of God’s genome, since He gives to one person ‘five talents’, to a second ‘two talents’, and to a third ‘one talent’. Nobody knows where the talents come from and why we have them. For Christ, the important thing isn’t so much how many talents you have, but more what you do with them. Here were have two attitudes, two ways of dealing with the issue. There are those who work hard to increase the talents they been given (two-four, five-ten); and there are others who keep the gift to themselves and lock it away in the box of their egotism. The former enter into the joy of their Lord, while the latter are banished to the outer darkness.

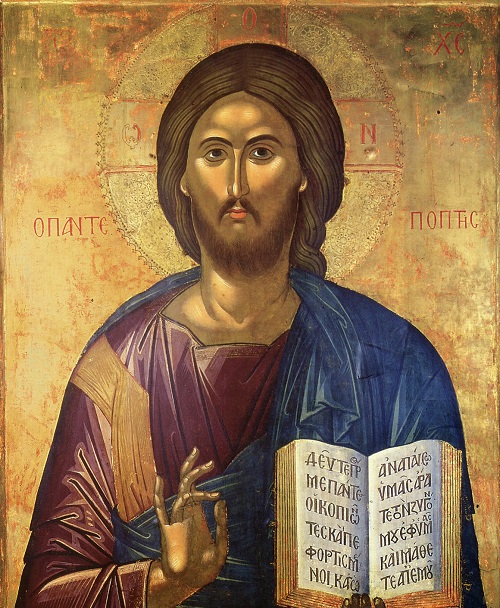

And so we come to the the third and final image (25, 31-46) in which the framework of the relationship is posed dynamically and one-sidedly, ‘in his glory’ and ‘on the throne of his glory’. Christ comes as the rising Sun. A motion of life-giving power which is independent of the choices and wishes of people and of the creation at large. ‘All the nations will be gathered’ under the eyes and the light of Christ, the true Sun of Righteousness.

With its presence and light, the natural sun reveals to our mind and eye what is in the darkness. With His glorious presence, Christ separates people, in the same way as a shepherd separates the sheep from the goats. He doesn’t make the ‘sheep’ and the ‘goats’. He finds them. His presence merely reveals the difference between them and what, before He came, was confused, unclear and intermingled (good with bad, pain and kindness, tears and callousness, death and well-being in general, the stumbling-block which is our world). Now, everything is settled in its true, permanent and clear position.

Eternity isn’t something, it’s someone. It’s Christ. Life is Christ. And life after death is our relationship with Him. But there’s a relationship of similarity and a relationship of revulsion caused by our love of self. He loves everyone, ever and always, with the same intensity: the Mother of God, the devil and all of us people to exactly the same extent.

The quality of our relationship with Him depends on us. It depends on our willingness to sacrifice in order to acquire ‘oil’ for the vessel of our existence. It depends on how hard we work to double the ‘talent’ that He gave us. It depends on the love we’ve won by cultivating the virtues His will has indicated to us, so that we can learn to love. He Himself is love. If we imitate His manner and keep His commandments, we gain love and so we become like Him. We become His children. Our encounter with Him is inconceivable joy. It’s the relationship of Paradise. But all this effort starts from here: ‘Here is Paradise…’.

Christ puts the same ‘questionnaire’ to both sets of people: Did you care about the hungry and thirsty? The stranger? The immigrant? The naked? The sick? The prisoner? Christ identified Himself with all these people. Those who work at the observation of the commandments (fasting and restraint- not as justifying achievements, but as a way of gaining freedom from selfishness and of establishing prayer as a relationship of participation in the love of Christ) enter the generosity of God’s love and acquire selfless love themselves. They respond to Christ’s ‘questionnaire’ with the joy and happiness of meeting a familiar acquaintance. Christ’s presence has become eternal, a permanent source of ever-increasing happiness for them. They can’t get enough of the light.

Those who retreat into the deception of egotistical, selfish love in order to avoid losing, sacrificing and labouring are unable to respond to the sacrificial love of Christ on the Cross, because of their love of self. In fact, His presence annoys them, because they imagine Him as someone who steals the ashes of their extinguished and cold love of themselves. So Christ becomes ‘inexpressible agony’ for them. This is a Hell infinitely worse than that naively presented in folk-art lithographs as fire and brimstone. The ‘outer fire’ of which the Gospel speaks is the ‘fire’ of the existential, eternal torment of being shut into total, permanent loneliness. As we’ve said, it’s not a furnace. When other people are merely exploitable opportunities (in professional, erotic or social terms), then we’re already on the road to Hell. Like Paradise, Hell is here, too.

Every day, the sun rises for the whole world. But if I pluck my own eyes out and then can’t see it and am left in the dark, that’s not something that God’s arranged; it’s my own doing.

Sin destroys the opportunity to share in God’s love, because through sin (spiritual or bodily) we become enclosed within ourselves. Sin isn’t fear among the old over the unknown quantity of their death, but an existential incapacity that deprives each person of the chance to taste the Lord’s goodness.

So we should now correct the old folk song to: ‘Here Paradise begins and Hell does, too’. Christ doesn’t send anyone to Hell. We choose to live far away from Him of our own accord.

My friends,

Let’s make Christ and His will the centre of our life and way of living.

Let’s strive to emerge from the shell of our egotism and learn to love.

Let’s rejoice at the majestic prospect of meeting Him: in the short term, at the coming Easter; permanently, in the embrace of Him Who is ‘the land of the living’.