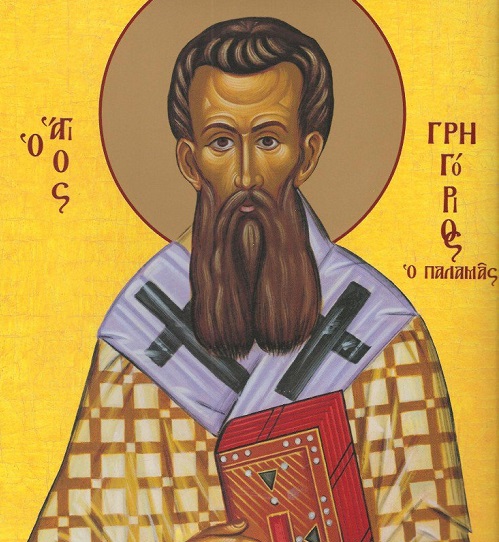

Saint Gregory Palamas, Archbishop of Thessaloniki

14 March 2020The progression from the first Sunday in Lent, which is dedicated to Orthodoxy, to the second Sunday, which is dedicated to Saint Gregory Palamas is of double significance: on the one hand it extends the feast of Orthodoxy, for which Saint Gregory Palamas struggled and suffered so greatly; and on the other, it underlines the need for the completion of Orthodoxy [right thinking] with orthopraxy [right acting], to which the saint also devoted himself with great zeal. Unless Orthodoxy is aligned and connected with orthopraxy, there can be no true Christian life.

Saint Gregory Palamas (1269-1359) is one of the greatest Fathers of the Church. Indeed, on occasion he has been mentioned as the fourth hierarch, together with Basil the Great, Gregory the Theologian and John Chrysostom. Or has been called the new Chrysostom.

After Saint John the Damascan, who lived in the 8th century and summarized the dogmatic teachings and Christ-centered content of the Christian life, a new period began. This was characterized, on the one hand, by the further cultivation of empirical theology and, on the other, the growth of sterile conservatism and Christian humanism.

The spirit of sterile conservatism and humanism in the 14th century was promoted in Byzantium by Barlaam, from Calabria in Italy, as well as other theologians such as Grigorios Akindynos and Nikiforos Grigoras. Although these latter did condemn some of Barlaam’s positions, they still approached theology as an intellectual exercise. Saint Gregory Palamas’ rejection of their theology was based on the living tradition of the Church. So in that new period, with its own problems, the voice of the Church had itself to be new, and was heard from a theologian who experienced and ‘suffered the things divine’, as was true in any case with all the Fathers of the Church.

At the basis of Patristic theology and of the theology of Saint Gregory Palamas there is the experience of the presence of God in history. This experience cannot be approached through logical questioning but only through the experience of the acceptance of and familiarization with divine dispensation. Elder [Saint] Sophrony Sakharof said that without Saint Gregory Palamas we would not have been able to come to terms with our own present age.

The theology of Saint Gregory offers the key to the development of Orthodox, theological self-awareness and its expression. This is why the revival of Orthodox theology, which became noticeable in the middle of the 20th century, was directly linked to the deployment of the theology of Saint Gregory Palamas.

The central position in the saint’s theology is occupied by the distinction between essence and energy in God. This distinction, which has its roots in Holy Scripture, was developed theologically by the Cappadocian Fathers. Saint Gregory Palamas used this distinction, emphasizing the uncreated nature of divine energy.

This emphasis was not a theological innovation, but had theological gravity. Every nature has its own concomitant energy. Created nature has created energy; uncreated has uncreated.

God does not dwell far away from us, nor is He linked to us through created means. He comes into immediate and personal communion with us through uncreated energy or His uncreated energies. In this way, we can engage personally in the divine life and become gods by Grace. In the final analysis, the whole of Palamite theology comes down to the defense of the truth of our renewal and deification in Christ, in other words our promotion to the state of a person made in ‘the likeness of God’.

We people, having been created ‘in the image and likeness of God’ are superior to the angels. This is why we praise the Mother of God as being ‘more honorable than the cherubim and beyond compare more glorious than the seraphim’. It was the pre-eternal will of God which placed us at this height. As Saint Gregory Palamas says, among the whole of creation it is only we humans who have the capacity in our nature to invent and produce the multitude of arts and sciences. We are therefore able to till the land, to build and create non-existent things, although we do so out of pre-existent matter rather than from nothing, which God alone is able to do [1].

In other words, among all God’s creations, we alone have the privilege of creating what we call civilization. Through civilization, we externalize our internal world. In this way, each civilization reflects the preferred choices, the expectations and the achievements of human society. And our civilization is first and foremost the product of our intellect and manifests its quality.

The human mind, which is the main seat of the ‘image of God’, functions best when it is in communion with its archetype, God. According to Saint Gregory Palamas, when the human mind distances itself from God, ‘what is brutish becomes demonic’. It oversteps its natural limits and is alienated, carried away with love of money, ambition and sensuality [2].

This phenomenon is world-wide and enduring, but is especially so today when the brutalization and demonization of people is on display in all its dreadful magnitude. Love of money, as a second form of idolatry, is the bane of our whole planet. People, as well as the whole earth, the sea and the air, are choking in the toxic fumes of those in pursuit of money. One bait which these people use, today as always, is lending money at interest. Saint Gregory refers to this issue at length, pointing out its disastrous social dimensions. Money-lenders pollute not only their own soul, but the whole of society, attaching to it [their soul] the crime of misanthropy. They destroy the life of the borrower, as well as their soul. Interest is the ‘spawn of vipers’ nestling in the bosom of the avaricious. But even if you say that, rather than charge interest you’ll just keep your extra money to yourself instead of lending it to those in need, you are in the same position, according to Saint Gregory [3].

Where there are usury and avarice, there you will find exploitation, oppression and sensuality. People ignore or neglect their surpassing majesty, their very humanity, and become brutish. In this way, the civilization they create proves to be toxic and inhuman. Such is the, otherwise brilliant, civilization created by people today. Our majestic but malicious mind is reflected in our culture. Unless we cleanse our mind from spite and restore its link to its archetype, to the God in whose image we’re made, we shall end up becoming ‘brutish or demonic’.