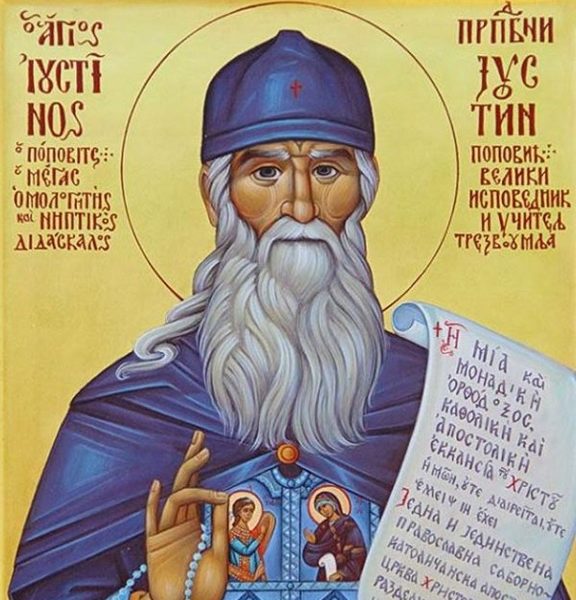

St Justin the New (Popović) on Papacy

11 January 2021St Justin Popović’s critique of papacy is one of the most recurrent themes in his entire opus. One may detect in Justin’s view of papacy several elements, some that remain permanent in his works and some that depend on the historical context and circumstances. For example, Justin’s criticism of papal infallibility and of the papal claim to universal jurisdiction are recurrent. However, his views on the Vatican’s ecclesial policy, expressed as a critique of union, concordat or joint ecumenical activities are not a constant element in Justin’s approach to papacy. In the following lines I intend to focus on the early, middle and late period in Justin’s life and to explore the similarities and differences in his approach to papacy in these three periods. I will first examine St Justin’s early critique of Papacy from his Oxford BLitt thesis on Dostoyevsky and the articles published in the journal Christian Life. The focus will then move to the period of 1930s and 1940s. Finally I will scrutinize Justin’s late ecumenical works, as well as his letters to the Holy Synod from the 1970s.

In his work ‘Philosophy and Religion of F. M. Dostoevsky’, an Oxford dissertation written in 1919 for the degree BLitt,[1] and later published in Serbian in the journal Christian Life,[2] the young Justin exposes his ecumenical, or rather anti-ecumenical position. By following Dostoevsky, the Serbian monk primarily criticizes the Roman Catholicism, and with it the entire European and Western civilization. According to Justin, all difficulties that confront the European people are caused by denying Christ his divine attributes, and by reducing him to a man, the European man:

“The European man did not want to adjust himself to the God-man out of pride, but he adapted the God-man according to himself – a man. For a long period the European man has been overestimating himself at the expense of the God-man, until he reached the climax of his insanity: a vain dogma of the infallibility of man, which in itself synthesizes the spirit of Europe”.[3]

According to Justin, by promoting the papal dogma of infallibility, Roman Catholicism has become the cause and the origin of atheism, socialism, anarchism, science, culture and civilization according to man.[4] Similarly to Dostoevsky, Justin sees the main reason for issuing the papal dogma of infallibility in the Pope’s intention to unite lands and peoples under his spiritual and earthly rule.[5] According to Justin, all social processes, which took place in the last centuries in Europe in the form of protests and the Reformation, were just a response to this papal claim.[6] In an attempt to respond to all these processes, the Roman Catholicism transformed itself, for Justin, into the idolatry of the infallible man in Rome, while the Protestantism, as a reaction to papal claim, transforms itself slowly either into atheism, or into “flexible, floating, variable (but not eternal) morality”.[7] However, the main problem of the papacy lies, according to St Justin, not in an unsatisfied desire for power, but in its attempt to mechanize the person almost to destruction.[8] The self-preservation of one’s own ‘I’, which was inaugurated by the papal dogma of infallibility, became the principle of Western science and civilization. For Justin, this desire for self-preservation is the denial of the notion of personhood, which is based on sacrifice or on giving oneself to others. The European science is powerless to solve the problem of personhood, because it atomizes the person, reducing it to impersonality. By declaring ‘self-preservation’ as its basic principle such science leads to nihilism, which on a personal level, in the last instance, ends in suicide.[9] Similarly to the European science, the European civilization has rejected, according to Justin, the God-Man Christ. Therefore, as a small part of humankind, the European civilization cannot rule over the rest of the world, because the ultimate consequence of these contradictions will be a final and devastating political war.[10]

For Justin, only the connection between the human person and the person of the God-man Christ reveals the mystery of the human personhood. The basic characteristic of the human personhood is the connection to the person of Christ, by which human being discovers in himself something immortal and eternal, Christ-striving and God-likening.[11] Justin’s basic concern is to preserve the idea the personhood established on sacrifice for others and not on the principle of self-preservation. Therefore, he is critical of the papal claim to infallibility as an epitome of this tendency in the European culture.

One may arguehat due to his criticism of the papacy in his Oxford dissertation Justin adopts an anti-ecumenical stance. However, such a conclusion may be drawn only from a perspective, which does not take into account the historical context of distrust between the different Christian denominations that prevailed in the second decade of the twentieth century in Europe. This distrust began to weaken with the first ecumenical gatherings, such as the conference of Protestant Churches summoned in Edinburgh in 1910. In any case, Justin’s earliest published work should not be taken in isolation from other works published in the same period, mainly in the journal Christian Life.

A quick glance at Justin’s authorial and editorial work in the Christian Life, reveals several tendencies in ecumenical affairs, such as a strong critical attitude toward Roman Catholicism and Vatican’s Ostpolitik and benevolence toward the Anglican Church. Justin’s critique of Roman Catholicism exposed in his dissertation on Dostoevsky was complemented by a series of critical remarks on the policy of the Roman Catholic Church in Europe at that time. Justin comments upon the encyclical of Pope Pius ХI from 12 November 1923 issued to mark the tercentenary of the repose of St Josaphat, the Uniate Archbishop of Polotsk, in which the Pope urged the ‘Orientals’ to ‘get rid of their prejudices’ and return to the Roman Church.[12] Justin argued that the office of the Uniate Archbishop Josaphat resulted in great persecution and forced conversion of Orthodox Christians in Poland and the capture of more than 300 temples that belonged to the Orthodox.[13] Justin reacts also to Jeraj’s article ‘The Crisis of Slavahood’ published in 1927 in Ljubljana, in which the author prescribes the papal universalism of the Catholic movement as a therapy that heals the western Slavs from the alleged sickness of German rationalism and subjectivism, and the eastern Slavs from the alleged sickness of Orthodox ascetical mysticism.[14]

Several points need be mentioned here. First, in his Oxford dissertation the young Justin largely identified his views on the western churches with the views of Dostoevsky, as it was indicated by his examiners, who called for a critical reflection. While the views of Dostoevsky might be an intellectual construct, based more on abstract speculation about Western churches than on the living experience, the young Justin had a chance in Oxford and London to get acquainted with the living Christian tradition of the West. On the basis of this experience, Justin sharpened his critical views of papal claims to universal jurisdiction, which were also targeted by Anglican theologians. Therefore, Justin’s views on the issue of papal infallibility and papal universal jurisdiction did not alter, but they gained a new critical strength as reactions to Vatican’s policy in Yugoslavia. Justin argued against Protestantism, by considering it as an expression of Roman Catholicism, and as a kind of humanist Christianity, but he never rejected its Christian character nor dismissed the need to enter in a dialogue with Protestantism. His criticism of the Serbian Church for failing to respond to the invitation for the Stockholm ecumenical conference in 1925 is a valuable proof of his openness. Justin’s ecumenical openness is most visible in relation to the Anglican Church, with which the Orthodox Church aimed to establish not only close ties, but also a prospective unification.

Justin’s views on Roman-Catholicism and papacy are deeply connected with the new reality of Yugoslavia, a state created with the strong feeling of pan-Slavic unity. There were political forces in Yugoslavia that propagated the cultural values dominant in the political systems of Western Europe. In Justin’s views, in spite of the evident progress in securing the well-being for its people, Western Europe underwent drastic changes of secularization that already had some bleak consequences like the WWI. In light of the increasing popularity of communist and revolutionary ideas that gained great political support among the people of Yugoslavia, another possible direction of the newly created country was to follow the revolutionary road of Russia. None of these possibilities were acceptable for Justin, because both proclaim as the highest value not the incarnate God or the God-man but the human being. For Justin, the only difference between European and Soviet humanism is that the former identifies itself with Christianity, while the latter is atheistic in nature.

Justin relies in his criticism of European humanism on some Slavophile ideas, but he does not propose a solution that is not intrinsic to his own culture. By projecting the dilemma between East and West back to the Serbian Middle Ages, Justin proposed a solution apparently offered by the founder of the Serbian Church and its first archbishop St Sava Nemanjić. St Sava’s independent position from the dominant political and ecclesial paradigms of Rome and Constantinople enabled Justin to develop Svetosavlje (Saint-Savahood)[15] as a tertium quid metaphor meant to transcend East and West narratives. In his works written during the 1930s, in the context of the Yugoslav Concordat crisis,[16] Justin argued that the papacy was the father of fascism and communism, because it employed violence in the name of God, while communism and fascism used violence in the name of class and nation. For Justin, the Serbs could resist these challenges, only by relying on Svetosavlje.[17]

Although this might sound odd, especially in the light of his criticism of papacy, for Justin Svetosavlje provided the foundation for the Yugoslav national and ecumenical project. Like his mentor Bishop Nikolaj Velimirović, Justin opposed the Pope’s power over Catholics in Yugoslavia, because he perceived it, similarly to the ecclesial rule of the Constantinopolitan Patriarchate over the Orthodox Serbs in the Balkans, as an expression of ecclesial imperialism. Svetosavlje is presented in the works of Justin as both the national and ecclesial principle realized within the limits of time and space and the idealized model of the Christian past presented as the future and universally desired image of a Yugoslav society. Thus, Svetosavlje became the eschatological goal to which the Yugoslav state and society, as well as the Yugoslav Church liberated from the ecclesial rule of Rome and Constantinople, should strive. Although St Sava is a historical figure and a national leader, Justin’s doctrine of Svetosavlje has been deprived of any national element that is different from or contrary to evangelical principles. By placing St Sava and Svetosavlje not in the national history, but in the eschatological realm that transcends history, Justin intended to establish an ecumenical platform that is also acceptable for Roman-Catholic Croats and Slovenes. With the crisis of Yugoslav national idea and the turmoil that preceded the WWII, Svetosavlje ceased to be the basis for national and ecclesial unity and it became a more intrinsic ecclesial principle.

From the mid 1960s onward the question of ecumenism and the relationship of the Orthodox Church to it, was in Justin’s focus. Although his book The Orthodox Church and Ecumenism is mainly a compilation of his interwar writings on western Christianity, the chapter ‘Man and the God-man’ reveals his mature views on papacy previously exposed in the article ‘About the ‘Infallibility’ of the European Man’ from 1969. Justin recapitulates his stance on man and the God-man, Europe, humanism, papacy and the dogma of papal infallibility. By the end of this chapter, Justin reflects on the contribution of the Second Vatican Council. He argues that by reaffirming the inviolability of the papal dogma of infallibility adopted at the First Vatican Council, the Second Vatican Council is “the renaissance of European humanism, and therefore Renaissance of corpses”.[18] Besides such a bleak diagnosis Justin offers a solution, which consists in the wholehearted and transfiguring repentance before the God-man.[19] For Justin, the repentance leads to the knowledge that: a) the true ecumenism is a catholicity of people gathered in the name of Christ (Matt. 18:20) and Christ in their midst; b) the Holy Spirit dwells in God-human and not in humanistic categories; c) one needs to ‘preach not ourselves’ (2 Cor. 4.5), but the Lord; d) humanism and humanist Christianity derived from papism is a heresy.[20] Thus, not only the rejection of papal dogma of infallibility by the Pope, but also the rejection of the infallibility in matters of faith by every man and woman in Europe and their repentance before the God-man creates for Justin a possibility for true union and true catholicity and ecumenism in the true Church. However, the harsh criticism of papacy should not be read at face value, but rather as a critique of the ecumenical policy of the Orthodox Church. In his letters to the Synod of the Serbian Orthodox Church, Justin criticizes the Ecumenical, Russian and Serbian Patriarchates for the same sins as those attributed to the papacy. For Justin, the bishops of the Orthodox Church preach “ecumenism of Protestant syncretism and eclecticism based on a fruitless European humanism and frantic European anthropocentrism”.[21] Moreover, Justin considers that the alleged ‘neo-papist’ tendencies of the Ecumenical Patriarch and the papal claims to universal jurisdiction and infallibility have the same humanist roots.[22] In Justin’s view in both cases a man, the Pope in Rome and the Patriarch of Constantinople replaces the God-Man. For Justin, the attempts of both the Constantinopolitan and the Moscow Patriarchates to create a ‘super-Church’ by imposing juridical authority on the new churches in the Orthodox Diaspora may be compared with the papal claim to universal jurisdiction. This does not mean that Justin a priori rejects any kind of ecumenism. Justin distinguishes between the humanist ecumenism, which the unity of the Church secures by mutual concessions and compromises, and the God-human or Orthodox ecumenism, which is, for him, a testimony of the God-human Truth spotlessly preserved in the Orthodox Church.[23] He does not deny the need for theological dialogue with the Western churches, but he rather points out that those who adhere to the patristic Orthodoxy are obliged to pursue such a dialogue. Justin strongly disapproved the participation of local Orthodox churches, and particularly the participation of the Church hierarchy, in building a super-ecclesial ‘body’ under the patronage of the WCC or of the Roman Church, as well as joint prayers and worships.

In conclusion, one may distinguish in Justin’s critique of papacy dogmatic elements on the one hand and political and cultural elements on the other hand. In his dogmatic approach to papacy, by focusing on the issues of papal infallibility and the claim to universal jurisdiction Justin is quite traditional from the Orthodox point of view. In his views, bby insisting on these two elements in their papacy, the modern popes differ themselves from the first millennium God-bearing bishops of Rome. However, in his cultural and political critique of papacy, Justin blames the papacy for some modern social phenomena. Thus, in Justin’s early works, the modern papacy is the epitome of humanistic tendency in the European culture to deprive human personhood of the deepest connection with the God-man, and for Justin the papal claim to infallibility substantiates this tendency. By relying on Nikolaj Velimirović, Justin criticized the papacy as an expression of ecclesial imperialism in the interwar period. The papal interference in Yugoslav political affairs through the concordat and the Pope’s dominion over Catholics in Yugoslavia were for Justin expressions of papal imperialism, which were in stark contrast to the anti-imperial direction of the Yugoslav society. Finally, in his latest works and letters, Justin’s critique of papacy reflects his critical attitude towards the ecumenical policy of the Orthodox Church. The modern ecumenical dialogue for Justin is not inspired by humility and repentance before the God-man, but on the contrary by the humanist will to power, equally expressed in the policies of the Roman Pope and of the Constantinopolitan, Russian and Serbian Patriarch. In all of the aforementioned cases, the papacy for Justin remains incompatible with the God-human Christianity.