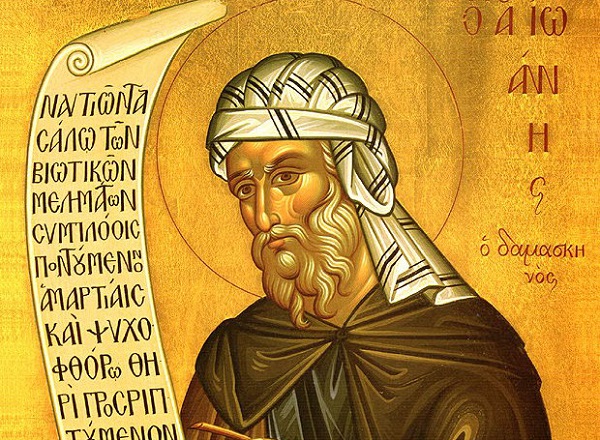

Saint John the Damascan: the hymnographer of popular theology

1 September 2021Saint John the Damascan lived between the 7th and 8th centuries and was one of the most well-read and ascetic Fathers of our Church. Verifiable information on the life of this Syrian monk from Damascus is limited and, essentially, is to be found in the older synaxaria. He was a prolific writer, and his contribution at the time of the dispute over icons made him one of the most outstanding historical figures of the period. His anti-heretical teaching, his immersion in philosophy as well as his exact exposition of the theological teaching of seven centuries in clear, succinct sentences, contribute to his standing as one of the leading personalities in Byzantine intellectual life in general.

Saint John is well known also for the book of the Octoechos, which is ascribed to his name. This is the book which contains all the resurrection hymns for the whole of the liturgical year. The Octoechos is also the core of the Paraclitic which is in use today and which, besides the hymns of Saint John, contains poems by other hymnographers, such as Emperors Leo VI, the Wise, Constantine VII Porfyroyenitos et al.

But the Church hymns which came from the hand of Saint John, and, in general, those we find in all the liturgical books of our Church (Minaia [services of the month], Triodio or Pentikostario) aren’t merely compositions created in accordance with certain metrical or poetic rules and laws. They are also the condensed, personal expression of Orthodox theology and the experience of the Church, throughout all the centuries of its existence. In other words, the various hymnographers, who were, necessarily, saints steeped in the learning of the Church, undertook the task of rewriting the teachings of theology, of the great ecclesiastical events, of the synods and of the Fathers, in a language which was simpler and poetic. Indeed, it has been remarked that at the time of the great hymnographers, unlike today, there was no separate class of ‘composers’ who would have set the poetic hymns to music. Rather the hymnographers both wrote the poems and then set them to music themselves, so their skill and contribution is doubly impressive.

Saint John, then, was not only a hymnographer but also a leading figure in the theological and academic affairs of the period, since he also summarized the theological teaching of the Church as it had developed until his own times and wrote analytical philosophical works similar in form to those of Aristotle. He was important in hymnography, too, for reasons similar to those which made him outstanding in theology. Just as this exceptionally gifted Syrian monk recapitulated and summarized the whole theology of the Church in his works, so, in his hymns, he wrote compositions which make up the core of the yearly liturgical cycle of its worship. Indeed, he’s among the most prolific hymnographers of compositions still in use today. To put it another way, he was the voice of the people. He transformed the elevated theological texts into encapsulated and metrical hymns, which he put into the mouths of the people. Because the Church’s hymns certainly belong to the people, since they’re sung by the lower order of clergy, the choirs, in order to be heard by the congregation. In fact, in earlier years, the very few hymns that were used in the first services were actually sung by the people and there were no special choirs. The priestly prayers and exclamations aren’t always directed to the congregation, but may be between the clergy themselves (‘Bless, Lord’, as the deacon says to the bishop) or directly between the clergy and God, in a low voice or as an exclamation.

But let’s look at some typical examples of the hymnographical skills of Saint John the Damascan. One resurrection stikhiro for Saturday, in tone 1, says:

‘By your Passion, Christ, we have been set free of the passions and by your Resurrection have been redeemed from corruption. Lord, glory to you’.

In a well-summarized and simple manner, this one, brief sentence contains the whole of the earthly mission of Christ as God and human person: his Passion and Resurrection, through which humanity was loosed from the bonds of the devil and is raised with Christ.

A dogmatic stikhiro in tone 3 on Saturday says:

‘A most mighty wonder. A virgin gives birth and her offspring is God before the ages. An unheard of birth and a feat beyond nature. A dread mystery: what is apprehended remains inexpressible; what is contemplated is not comprehended. Blessed are you, spotless Maiden, daughter of earth-born Adam, who have proved to be mother of God the most high. Implore him that our souls may be saved’.

This tropario obviously theologizes on the nature of the Mother of God. Again within a brief passage, it mentions most of the important things concerning her: the birth beyond nature, her contribution to the great mystery of our salvation, the blessed state of which she was deemed worthy and her powers of intercessional prayer.

Finally, a tropario from the Sunday resurrection canon in plagal tone 4 says:

‘How can we not wonder at Christ’s all-powerful divinity? From the Passion, it bestows on all the faithful freedom from the passions and from corruption; from the holy side it flows as a spring of immortality and everlasting life from the grave’.

In this exemplary tropario, also, there is the unmistakable presence of sublime theology for the use of the people in church. The Lord is presented as the all-powerful Savior of humankind, risen from the dead, the Father of immortality and of eternal truth.

Of great interest to modern hymnological and musical research is the remarkable phenomenon of how the difficult, densely-packed and precise theological texts of the Church, which often extend to several pages of Patristic writings or the proceedings of synods, were able to be transposed into metrical, melodic compositions, easily comprehensible to ordinary people. This research poses clear questions on the matter. What exactly happens to the content of these theological texts in the course of this transposition? Why were hymns chosen to express theology to people in church? Is the hymn the prime expression, the language par excellence, of theology? And, as regards their practical, melodic, musical aspect: are there any particularly appropriate meters and metrical motifs; how does the music to which the hymn is set affect people and what emotions does it stir in the soul in connection with the divine concepts which the hymns contain?

Saint John the Damascan lived roughly in the middle of the greatest flowering of the Christian Roman Empire. This particular circumstance contributed to the nature of the work he accomplished. In modern terms, he was a kind of encyclopedist of theology and philosophy. He was also, however, the most outstanding figure in the hymnographical production of the Church. As if he were another David, his poems have been used by the Church to express the beliefs of Christ’s flock. He is the hymnographer of popular theology.