The Theologian of Love

27 September 2021a) Theology, as discourse concerning some god, can be found in a variety of religions, even primitive ones. In ancient Greek thought, a theology developed which was founded on human discourse. But Christian theology, as the experience and record of personal communion with the God of Christian revelation, who ‘appeared in the flesh,was vindicated by the Spirit, was seen by angels, was preached among the nations, was believed on in the world, was taken up in glory’ (1 Tim. 3, 16), is entirely different. This is a spiritual event of a different order.

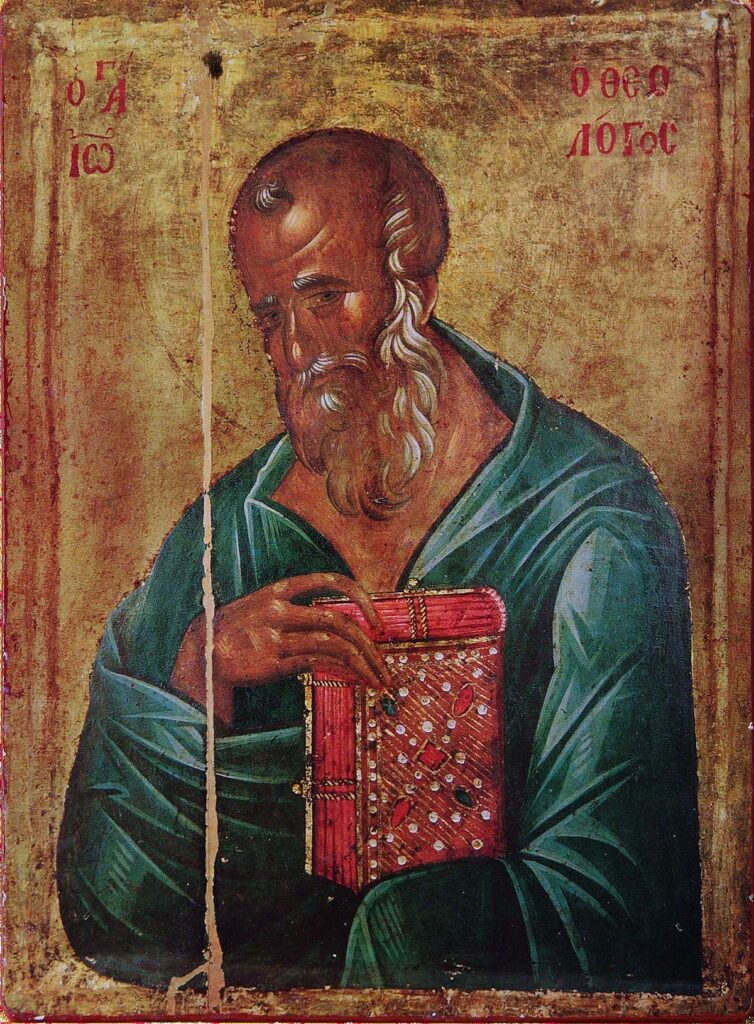

b) Although many holy Fathers and ecclesiastical writers have written important tracts, only three have had the designation ‘Theologian’ attributed to them: Saint John the Theologian, bosom friend of the Lord, whose memory we celebrate today; Gregory the Theologian (4th century; and Symeon the New Theologian (10th century). Although they lived in different eras, all three tasted the presence of God through uncreated grace and had commensurate spiritual experiences. Thereafter, inspired by God, they recorded these experiences without error in their writings, often in a poetic and symbolic manner.

c) As the beloved disciple of Christ, John the Theologian lived through many wondrous events at the Lord’s side. He preserved many of them in his Gospel and his Epistles, though he omitted many others. In the Revelation, he also describes the end times as the present, the ascending progress of the Church, the ongoing struggle of Christians with the wicked serpent of old, the devil, and the triumph of the Second Coming of the Lord. What he wrote is sufficient for us to believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God and that ‘believing we may have life in his name’ (cf. Jn. 21, 31).

d) In today’s Gospel reading, it says: ‘And there are also many other things that Jesus did, which if they were written one by one, I suppose that even the world itself could not contain the books that would be written’. Clearly there’s some exaggeration here, which serves to emphasize the amount of works performed by the Lord, as the commentator Zigavinos* notes. On the other hand, he also remarks: ‘the world itself could not contain them… not for the number of books, but because of the magnitude of the actions’.

e) And, indeed, how can we understand the spiritual power of Christian love, as described by John in his Gospel and Epistles, when, on a daily basis, we poison our lives with envy, injustice and hatred? How can we grasp the meaning of the dread, beguiling and topical Revelation, when we look at life through the prism of secular and economic affairs? But readers steeped in the Philokalic tradition, as disciples of the saints, patiently engaging in the struggle, understand that the Church, as a milieu of grace and sanctification, makes its way in history, through a host of temptations, dangers, hindrances and hardships. They also understand that, in the Revelation, glorification of any authority whatsoever- be it political, economic or ideological – is condemned very forcefully indeed.

f) Finally, the message of Christian love from God is certain, though from the side of humans it is something to be sought over a dramatic progression of misunderstanding, alienation, repentance and sanctification. Clement the Alexandrian relates how, in a certain town, John had baptized a young man and had entrusted the oversight of the community to him. On his next visit to the town, John was informed that the young man had become the leader of a band of robbers. In order to make contact with him, John put himself in the hands of the robbers. As soon as he saw him, the young man took to his heels in shame. John followed him and called: ‘Why are you fleeing, son? You still have hope of life. If necessary, I’ll die for you. The Lord sent me, believe me’. The man was completely overcome. He threw away his weapons and fell at John’s feet, asking forgiveness. At the same time, he concealed his right hand, with which he’d committed a great many sins. Saint John took the hand which had been cleansed through repentance and covered it in kisses. He took him back into the Church and presented him as an example of practical repentance.

g) Saint John the Evangelist had been transformed by divine love and, into the depths of old age, continued to teach: ‘My children, love one another’. Saint Païsios used to say: ‘Did Christ perhaps love John more than the other disciples? No, but John loved Christ more than the other disciples did, and this is why he understood Christ’s love better. He had great capacity and could hold more of the love of Christ. And the more Christ gave him, the more his heart melted’. If you open the eyes of your soul and dispel the dark cloud of the passions, you understand the love of God and valiantly observe his commandments. You don’t slavishly fear the signs of the times, but longingly await the rising of ‘the bright morning star’ (cf. Rev. 22, 16).