Saint Mary Magdalene (+ July 22): Minimizing an Apostle’s Role

22 July 2022The years 1976-1985 were named the “Decade for Women” by the UN. Within the context of the activities which were held then, the view was expressed, among other things, that religions bore the responsibility for the denigration of women’s rights. The Christian world responded to this challenge by launching its own decade (1988-98) of “Churches in Solidarity with Women”, under the auspices of the World Council of Churches. But the WCC had already become involved, in General Assemblies and individual activities, with this particular issue. Indeed, between the years 1978-81, a study programme was organized on “Community of Men and Women in the Church”. The culmination of this effort was the International Assembly in Sheffield, which produced the now famous “Sheffield Report”. During the course of all these discussions, the Christian academic community was given the opportunity to re-examine many related issues, such as, for example, the influences on the social life of the Western world from the theology formulated in the West in the 5th century A. D. by, perhaps, the greatest figure in the Western world, Saint Augustine, concerning original sin. Another very important matter which was re-examined historically and theologically in the Christian world, on the same occasion, has to do with the person of Saint Mary Magdalene.

In the artistic, philosophical and – until recently – in the Western ecclesiastical and theological world, outside that of the Orthodox Church, the name of Mary Magdalene has been identified, one way or another, with eroticism in the broader sense. Various artists or writers of fiction, such as, for example, Dan Brown, William Phipps, Chris Gollon, Martin Scorsese and many others have sought or desired to create a lover for Jesus from Nazareth and, curiously, every single one of them has lighted upon Mary Magdalene. This is not surprising since, for a long period, even within the sphere of Church literature, Mary was characterized as the most attractive and enthralling female person in the New Testament. Even today, many people think she was a former harlot, who, of course, repented after her existential encounter with Christ. One of the modern British artists mentioned above, Chris Gollon presents her in his painting “Pre-Penitent Magdalene” as a provocative femme fatale, wearing all the jewellery you’d expect and far too heavy make-up. On the same wave-length, but with serious symbolic poetic thinking, there is also the short text entitled “Magdalene” in Dinos Christianopoulos’ collection, The Time of the Lean Cattle (Thessaloniki, 1950).

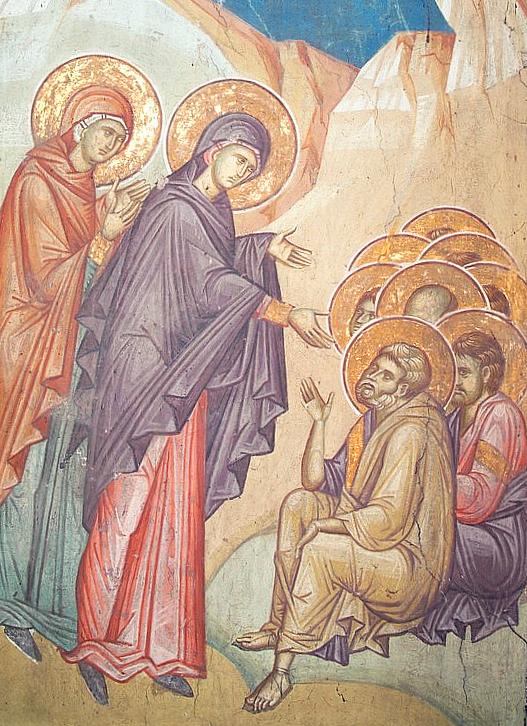

Saint Mary Magdalene teaching the Apostles about Ressurection, fresco, Decani Monastery, Serbia, 14th Century

And yet, nowhere in the reliable historical sources, particularly the oldest, i.e. the New Testament, is there any mention of this at all. On the contrary, in three of the four canonical Gospels, Mary Magdalene is mentioned by name only in the narratives of the passion and resurrection of Jesus Christ. In Mark, Matthew and John she’s mentioned as a witness of the crucifixion (“There were also women looking on from afar, among whom was Mary Magdalene…” (Mk. 15, 40). In John she’s placed last (standing at the cross of Jesus were his mother, and the sister of his mother, Mary, the wife of Clopas, and Mary Magdalene…) and was present at His burial (Mary Magdalene and Mary the mother of Joses saw where he was laid”, Mk. 15, 47; Matth. 27, 61). For the most part, however, Mary Magdalene is one of the first witnesses of Christ’s resurrection, that is of the empty tomb. Indeed, in John she’s the first such witness (Mk. 16, 1-8; Matth. 28, 9; Lk. 24, 1-12; Jn. 20, 14-18).

It’s only in Luke that Mary Magdalene is mentioned in testimony regarding the public ministry of Jesus before the story of the passion and resurrection, which is common to all four Gospels. At the beginning of chapter 8, Luke relates that Christ “ went on through towns and villages, preaching and bringing the good news of the kingdom of God. And the twelve were with him, and also some women who had been healed of sicknesses and scourges, of evil spirits and infirmities; Mary called Magdalene from whom seven demons had departed… who provided for him out of their means” (Lk. 8, 1-3).

The epithet “Magdalene”, which always accompanies her name, at least in the Gospels, implies that she wasn’t married, since, in that case, she’d have had her husband’s name. “Magdalene” indicates that this particular Mary came from the commercial city of Migdal (Taricheae) on the west bank of Lake Galilee, or the Sea of Tiberias. She must have been a wealthy woman, provided, of course, we believe Luke’s information, because she gave generous material assistance to the work of Jesus and his twelve disciples, which was revolutionary for the time. According to the same source, she had personal experience of the healing power of Jesus, probably through some kind of exorcism.

On the basic of a strictly historico-critical approach to Luke’s evidence, however, modern scholarship has some reservations, because in this particular Gospel there’s a clear tendency towards minimizing the role of Magdalene, in sharp contrast to the other three canonical Gospels. It should be noted that Luke is the only one of the Evangelists who maintains that the risen Christ appeared exclusively to Peter (Lk. 24, 34; see also I Cor. 15, 5. According to Ann Graham Βrock (Mary Magdalene, the First Apostle: The Struggle for Authority, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2003, pp. 19–40), there is no mention of any appearance of Jesus to Mary Magdalene in the Gospel according to Saint Luke. It follows , then, that the reference to seven demons, may well come from this prejudice, unless it has symbolic significance.

If this is the picture presented by the most primitive sources of Christian tradition, one might very reasonably inquire how it is that, with the passage of time, Mary Magdalene was transformed into a penitent harlot and, later, with a large dose of creative inventiveness, into something more than this.

Modern critical research has tended towards the conclusion that this resulted from a deliberate effort on the part of later interpreters of the history of the Christian message to gradually play down her role, at least as this is presented in the most ancient sources of the Gospel tradition. How this happened has to do, initially, with the gradual, and obviously unsubstantiated, identification of Mary from Magdala with other women who are referred to in the Gospels. First of all, with the anonymous woman from Bethany who poured myrrh onto the head of Jesus, a purely symbolic action which recognized Jesus as the Messiah, and which occurred shortly before His betrayal and crucifixion (Mk. 14, 3-9 and Matth. 26, 6-13) We should note that this action is to be interpreted as a “practical” confession of Jesus as Messiah, in much the same way as Peter’s verbal acknowledgement in Caesarea Philippi: “You are the Christ, the Son of the living God” (Mk. 8, 28).

In the later Gospels, the scene of this anointing of Jesus is transposed to the beginning of Christ’s public ministry (by Luke to 7, 36-50) and, significantly, the myrrh is not poured onto His head, but His feet, in both Luke and John, though the latter does retain the chronological moment of the event as being within the history of the passion, while identifying the anonymous woman with another Mary, the sister of Lazarus). Luke adds the motif of repentance and the subsequent forgiveness of the woman’s sins by Jesus.