God’s righteousness

24 March 2023In the Lord’s wonderful Beatitudes, recorded in the Gospel according to Saint Matthew (5, 3-11) as the introduction to the Sermon on the Mount, there are two verses which refer to righteousness as a condition of the kingdom of God. The first is verse 6: ‘Blessed are those who hunger and thirst after righteousness, for they shall be filled’; and the second is verse 10: ‘Blessed are those who are persecuted for righteousness’ sake, for of such is the kingdom of heaven’. In the first of these verses, it appears that initially Christ is referring to righteousness in society, in the way people live; while in the second the reference is to eschatological righteousness.

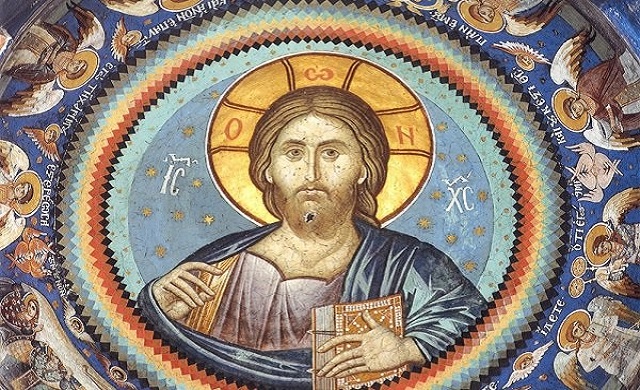

Jesus introduces the great theme of righteousness by way of an image describing the physical needs each of us experience, hunger and thirst, thereby showing that it’s as vital as the basic elements of life. What this righteousness means is set out by Matthew the Evangelist in his description of the three temptations Christ underwent and which, in essence, are endured by all people. If the necessities of human nature imprison us and trap us into dependency on the goods and forces of the created world, Jesus, as the new Adam, answers that we do not live by bread alone, that we don’t submit to magical and irrational powers, and that we aren’t interested in earthly kingdoms. What is highlighted by Christ is the harmonization of his will with that of his heavenly Father. This is the righteousness which is introduced into history, but which has as its prototype the righteousness of God.

This righteousness was revealed by the Holy Spirit to the prophets, who describe it as the name of God. When the divine law was handed down to Moses, the Lord made his name known: ‘The Lord, the Lord, the compassionate and gracious God, slow to anger, rich in mercy and true and maintaining righteousness and mercy to thousands’ (Ex. 34, 6-7). Essentially this has to do with God’s fidelity, which culminated in the incarnation of his Son.

Christ’s righteousness is referred to in the gospels as sacrificial righteousness. Moreover, for those who hunger and thirst after righteousness he offers another way of satisfying this need: partaking of his body and blood. ‘Take, eat… All of you drink of this’. Remember what he said to the Samaritan woman: ‘Whoever drinks of the water I will give them will never thirst again’ (Jn. 4, 14).

So this has nothing to do with some abstract notion of righteousness, but with that which springs from the will of God. God is called righteous and his righteousness is identified with love. The whole task of the divine dispensation, culminating in the incarnation of the Son, all his actions, were expressed as divine righteousness, as they continue to be. Can the world accept such righteousness, which is expressed as love? History tells us it can’t. As the Epistle to Diognetus puts it: Christians ‘love everyone and are persecuted by all’.

The life of Christians finds contentment in this righteousness of God. And, as we’ve already said, hagiographic sources equate it to love. Saint John the Evangelist tells us that God is love, i.e. he’s righteous. This righteousness doesn’t come to us from him as an individual accolade. It’s there in any case, and acts in the faithful if they’ve trained themselves to be able to receive and accept it. This training is called ‘cleanliness of my hands’ by the poet (Ps. 17, 21). ‘Cleanliness of my hands’ means actions. What the faithful give to God is their belief and submission to his will. What is given by God in return is his presence as righteousness, that is, as love. This sending back is summed up in the expression ‘divine grace’. Remember the prayer we send up to the Lord after the consecration of the precious gifts: ‘That our God, who loves humankind having accepted these […] may send down upon us in return his divine grace and the gift of the Holy Spirit’. This is the dynamic relationship between the created and uncreated: sending, and sending back in return.

The Hebrew text of Scripture renders righteousness as tzedakah. The translators of the Septuagint also had in mind the Wisdom literature which had emerged within the Jewish tradition and knew that God’s righteousness was equivalent to his mercy, or charity. Righteousness, in the end, is the same as God’s mercy or charity. God is righteous because he’s merciful. So in the Septuagint, the words are often interchangeable. At many points in the Old Testament, the translators of the Septuagint use the word alms-giving instead of righteousness. So the Lord’s blessing and charity are God’s gift to those who decide to ascend to his realm.

God’s righteousness is expressed through his presence and his presence means that of the divine, uncreated energies. If continuous spiritual exercise (including that of the body) allows the presence of these divine energies to act in us- ‘the kingdom of God is within you’ (see Luke 17, 21)- then the sin of this world is defeated. Christ’s declaration is clear ‘Take courage; I have defeated the world’ (Jn. 16, 23).

In other words, God’s righteousness is his loving-kindness. This is adumbrated in the pre-history of the Church, i.e. in the Old Testament, particularly in the prophets. Hosea is exceptional as regards this. This loving-kindness is identified with God’s name. As we said at the beginning, Moses learned God’s name on Mount Horeb: ‘ I am he who is’ (the Hebrew Bible has: ‘I am and will be who I was’). And this name is revealed and expanded on Mount Sinai: the Lord is plenteous in mercy, loving-kindness and truth. This is his name, but it’s one that moves through history like a shadow. It would become clear, as his righteousness, in a tangible manner, when we had his own Son with us.

Saint Paul develops this concept, stressing that, although we’ve all made mistakes and that because of these mistakes we’re lacking as regards the glory of God, we’re nevertheless vindicated, there’s righteousness which vindicates us through the grace which redeemed us, saved us, in the person of Jesus Christ, whom God gave to us as a sacrifice of atonement to remit our mistakes. With his blood, he achieved this redemption, so that his righteousness might be revealed, as a sign of his righteousness. This righteousness is revealed by the Son, Jesus Christ, ‘to demonstrate his righteousness at the present time, so as to be just and the one who justifies those who have faith in Jesus’. Righteousness isn’t a feature of God’s, it’s his name, the manner in which he exists. This righteousness of God has nothing to do with any righteousness that we humans may come to know, that we can develop and describe and, if you like, activate in our life. It’s another order of righteousness altogether, to which the prophet Isaiah calls us: ‘Learn righteousness you who dwell upon the earth’ (Is. 26, 9). It’s righteousness which justifies those who surrender themselves to Christ: ‘and justifies those who have faith in Jesus’.

The issue of righteousness played an enormous role in the history of Israel. The first person to be called righteous was Abraham. And he was deemed righteous not because he did things that we think of as righteous, but because he believed. It was his faith which made him righteous; faith in the sense of ‘trust’, of ‘surrender’. He trusted and surrendered to him who called him. In the case of Abraham there’s a call: ‘Leave here and go there’. And Abraham acceded to this call, that is, he developed a relationship of trust with him who called him. This is what we call faith. You’ll remember how Saint Paul deals with this matter of Abraham’s faith: ‘he believed in God and this was reckoned to him as righteousness’ (Rom. 4, 3; cf. Gen. 15, 6).

According to Saint Gregory of Nyssa (Against Eunomios 6, PG724D), God’s righteousness is the root cause of the salvation of the world (‘accordingly those who have been saved by the son, were saved by the power of the father’) and this righteousness is also the measure against which people are judged (‘and those who are judged by this are subjected to judgement by God’s righteousness’). In the end, God’s righteousness is Christ and he revealed this to us not only in his words but also in his actions (‘For Christ is God’s righteousness which was revealed in the Gospel’). Indeed, Saint John Chrysostom (On Romans 7, PG 60, 444), underlines the fact that, as God’s righteousness, Christ also justifies those who are in sin (‘but, also suddenly makes righteous those others who are festering in sin’).

So when we speak of God’s righteousness- ‘in your righteousness’- we refer to the presence of a real relationship. The mistake our first ancestors made was to sever this relationship. We’ve since tried to correct this initial mistake by making this relationship present. Have we succeeded? History says not. Even history since Christ says we can’t repair this relationship. What we can do, however, is accept the gift of this presence. That is very different. We accept the gift of this presence and, depending on the extent of our ascetic struggle, our willingness, we can surrender to it.