From Babel to Pentecost

12 June 2023Many scholars and historians consider ethnophyletism to be a phenomenon dating from the 18th and 19th centuries, a product of the Enlightenment, the French Revolution and the political theory of the self-determination of peoples. It was in this spirit that many nation states were created throughout Europe and the Balkans, based on ethnophyletic criteria without any refence to the religious factor. At the same time, these nation states proceeded with the nationalization of their Churches, with the same criteria. The Ecumenical Patriarchate considered ethnophyletism to be an obstacle to cooperation between local churches and condemned it as a heresy at a synod convened in 1872.

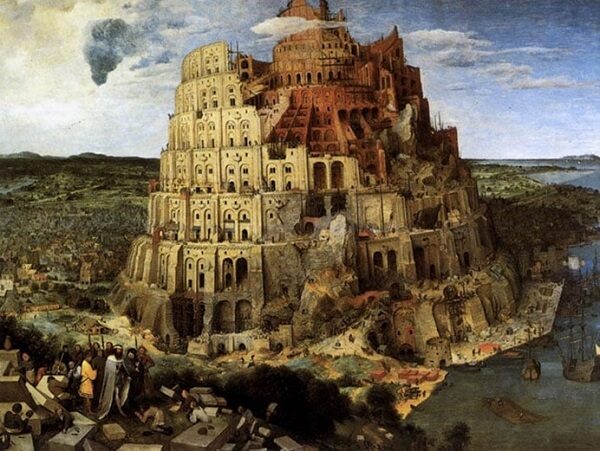

Pieter Brueghel the Elder, The Tower of Babel, Kunsthistorisches Museum, Vienna

In reality, however, ethnophyletism is a well-known and much-implemented phenomenon, the roots of which go back to the Old Testament. It’s no accident that on the cover of Nations and Nationalism, a book by the Marxist historian Eric Hobsbawm, there’s a picture of the Tower of Babel, which shows that the variety of peoples and ethnicities has Biblical roots. According to the Old Testament text, the Triune God caused confusion in the languages of humankind so that people couldn’t understand each other. ‘So the Lord scattered them from there over the face of the earth’ (Gen. 11, 8), as punishment for having dared build the Tower which was a sign of their arrogance. The peoples of the Tower of Babel were infected with the virus of phyletism, they sinned and gave in to temptation. The division of the nations was the result of sin and of the choice of a world without God, because ‘from one man he made all the nations, that they should inhabit the face of the earth; and he marked out their appointed times in history and the boundaries of their lands’ (Acts 17, 26).

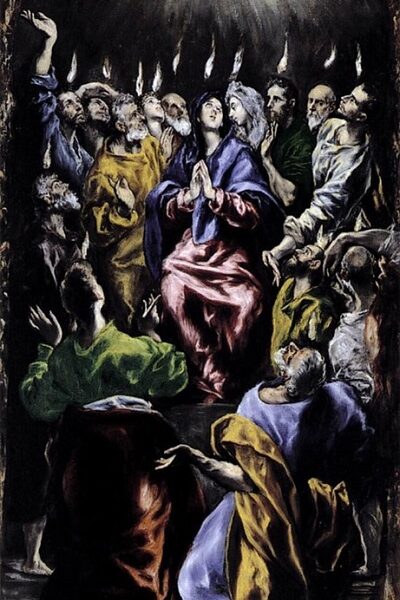

El Greco ‘Pentecost’ Museo del Prado, Madrid

However, in the New Testament, with Pentecost, the problem of communication between peoples no longer applies, since, by the grace of the Holy Spirit, the apostles ‘were filled with the Holy Spirit, and they began to speak in other languages’ (Acts 2, 4). Consequently, there followed a consensus among the nations, confusion was transformed into unity and relations between peoples were based on the Trinitarian model of mutual inherence.

Nationalism, by definition, excludes those who don’t belong to the nation. The Church, however, espouses criteria superior to those of race or culture, such as ecumenicity, and therefore has the capability of welcoming everyone into its bosom, without exception, and of treating them all as persons: ‘There is neither Jew nor Gentile, neither slave nor free, nor is there male and female, for you are all one in Christ Jesus’ (Gal. 3, 28).

On the basis of the Lord’s command to ‘go into all the world and preach the gospel to all creation’ (Mark 16,15), distinctions no longer apply and the theory of Jewish exceptionalism collapses: ‘Or is God the God of Jews only? Is he not the God of Gentiles too? Yes, of Gentiles too.’ (Rom. 3, 29). This was the temptation which kept them from joining the Church, even though they have never ceased to regard themselves as members of a chosen people.