‘I must feel her pain’

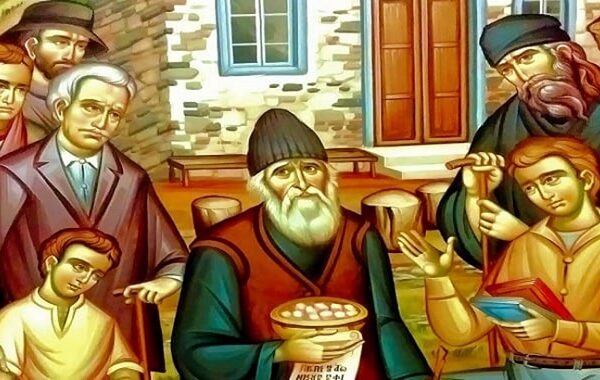

26 June 2023An acquaintance of Saint Païsios once asked him to pray for a girl who’d become involved with the occult. The saint said: ‘I have to feel her pain’. The man didn’t understand and thought the saint meant that he’d cause her pain, but was told: ‘Tell me something about her so that I can feel her pain and pray for her with pain in my soul’.

All believing Christians know the value of prayer and its power in the life of those who are praying and those who are being prayed for. Prayer’s a matter of life and death; without it Christians literally can’t live and breathe. The saints of our Church point this out: ‘We must pray more than we breathe’ (Saint Gregory the Theologian). And it’s obvious. How can we live naturally and joyfully without constant reference to God our Father, Creator, Provider and Ruler? Those who’ve expunged God from their lives have found out, even if they’re often not fully aware of it, that their lives have become hellish. Spiritual asphyxiation makes them experience death before their death.

And if prayer has absolute value and tremendous power for every Christian how much more is this true of the saints, that is for people whose faith in Christ is the absolute hallmark of their existence, whose body and soul are embraced by the sense of his presence? Of course, as evidenced by a very great many Christians, the prayer of Saint Païsios had awesome power. Thousands of people had recourse to his prayers every day, to be comforted, fortified and healed. And he exhausted himself for them. United in prayer with his Lord and God, he became Christ’s instrument, so that the latter’s almighty power could work on everyone in need and difficulty.

In the above instance, the saint reveals the secret of his own prayer, which is the essence of every prayer, if it’s to be heard by God. The prayer has to be said with pain for the person who’s being prayed for, be that oneself or someone else. And here’s something strange: the saint had rare power of prayer; he loved all of God’s creatures so much that his heart burned for them. But he still sought extra information, so that he could pray in an even more heartfelt way. ‘Tell me something about her so that I can feel her pain and pray for her with pain in my soul’. What do we understand by this? That prayers for people and their dire circumstances are certainly an obligation which expresses the love of the saint, but also that knowledge of their life is required, of the difficulties they’re likely to be facing, the weaknesses they might have. This is because the sensitive heart of the saint is particularly moved when he or she is able to put themselves in the position of the person who’s suffering spiritually or bodily. When we learn of the trials besetting another person, especially if it’s a friend or acquaintance, then, even if we have a heart of stone, we’re moved. This is infinitely more so in the case of saints. This means that a saint, even if he or she has the gift of foresight or insight, is not always in a supra-natural state. The opposite, in fact: the normal thing is that their lives continue naturally, like that of everyone else, and it’s unusual for them to be illumined in a fuller manner by the Lord. When this happens, they have the knowledge and information, everything human, at their disposal to pray, to express their heart filled with God’s grace.

We remember a similar case from the life of Saint Silouan. When he was the steward at a dependency of the Monastery of Saint Panteleimon he prayed with tears in his eyes for the laborers who worked at the monastery. And what kindled his prayer to such an extent that the men were able to feel its action? His knowledge of the life of each of them: one of them was living abroad to earn money to meet the needs of his family. ‘How does he feel, all alone, without his wife and child?’; or another one whose fiancée was waiting for them to get married, but they couldn’t afford it; or someone else whose child was ill and who was working abroad in order to cover the medical expenses; and so on. This knowledge of the circumstances and problems of each of them meant that he felt their pain and this pain took the form of prayer with tears.

There are an infinite number of examples from our saints. And they show us how we, too, can pray with greater fervor, that is with a greater sense of Christ’s presence and with greater trust in him and his willingness to do what’s best in our own life and in that of others. We’ll feel the pain of other people. When we hear of something troubling in their life, we’ll be moved to prayer, not to gossip or to the satisfaction of our curiosity. In other words, our imagination and knowledge will be weighed on the scales of love, not on those of delusion and demonic wickedness.