The meaning of pain in our life

14 October 2014 Apart from the suffering that it causes, physical, mental or spiritual pain– which entered man’s life by divine sufferance – also has positive effects for man’s earthly life and development.

Apart from the suffering that it causes, physical, mental or spiritual pain– which entered man’s life by divine sufferance – also has positive effects for man’s earthly life and development.

It is easy to philosophise or theologise about pain but it is difficult to have a proper attitude towards pain when one experiences great pain oneself. I believe it is very presumptuous to talk about pain when one has not experienced it oneself. I think of all our brothers all over the world who are suffering physical, psychological or spiritual pain.

Physical pain is experienced by people as a result of disease, hardship or hunger. Psychological pain is experienced by people who are persecuted or vilified, people who are unloved or neglected by the people they hold dear, and people who suffer from unfulfilled desires or the sickness or death of loved ones, amongst other things. Spiritual pain is experienced by all those who love God and man but see that through their sins they sadden God and offend against God’s image, man.

How did pain enter our lives?

Of course, pain did not enter our lives because God willed it so but because He permitted it when man, through his selfish disobedience, lost the Source of Life, his Creator. Leaving behind the painless state that existed in God’s Kingdom, man found himself in another state which, since the true Life no longer reigned, was dominated by a life of decay, bound up with death, the passions and sin.

The beneficial effects of pain

In this new state death and pain seemed to have a positive meaning, like the other leather garments with which God clothed Adam and Eve when they left Paradise to console them in their exile. Death puts an end to evil, which would otherwise exist for ever on earth.

Physical pain warns us of illness, so that an appropriate cure can be found. Doctors know how beneficial pain is. Likewise, all kinds of pain help us to become aware of our corruptibility and thus to know where our human limits lie, thus saving us from any form of self-deification.

Pain helps us to review where we are heading in our lives and to bring us back to their proper centre, which is the Triune God.

Pain helps us to refine our love for God, so that we might love God not for the gifts that He gives us (such as health and family happiness) but for who He is.

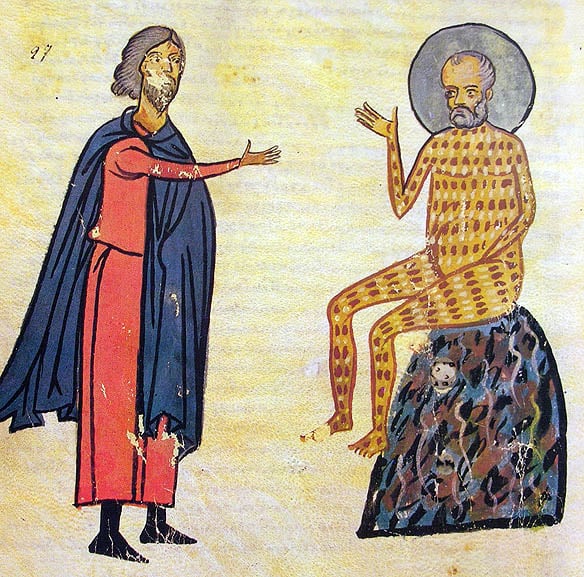

Thus the sorely tried Job, through the way that he faced illness and his other unbearable trials, showed that he loved God for who He is and not because of His gifts. When he lay in the dirt, covered with sores after losing his ten children, he loved God just as much as when he had been prosperous.

The Suffering of Job, Vatopedi Manuscript nr. 590, 12th Century

Pain also helps us to have a correct attitude towards our fellow men, whom very often, when we are not in pain ourselves, we scorn, wrong and hurt through our selfish behaviour. When the pleasure with which we exploit our fellow men turns into suffering, then we understand just how destructive our illicit pleasure is.

In many cases people who have experienced a great deal of pain have managed, through their pain, to find their true selves behind the masks and so thanked God for the gift of pain, even if it took the form of an incurable and painful illness.

In other cases pain can help spiritually mature individuals to attain higher forms of spiritual perfection, and to support and console many needy souls.

One example of this is the blessed Elder Paissios, who accepted the fact that he had the so-called ‘accursed disease’ (cancer) with joy, believing that sick people out in the world would be consoled by the fact that monks suffer as well. Thus for Father Paissios the ‘accursed disease’ became a blessing.

A theological understanding of pain

People who are in pain often utter the agonising question ‘Why God, why?’. I do not think that there is a human answer to this question. There is only one answer: God shared in our pain in the Cross of Christ. We believe in a crucified God, which means a God who has been humbled, humiliated and tortured. On the Mosque of Omar in Jerusalem there is the following inscription: ‘Let no one speak the blasphemy that God has a son’. Not so far away stands the Hill of Golgotha, where the Son of God suffered for us all. We are not ashamed to say that we believe in a God who became man, was crucified and rose again, in a God who, out of infinite love, shared in our illness and assumed our mortal and suffering flesh in order to make it immortal. An inaccessible, withdrawn and unsociable God would be impossible to believe in, impossible to feel for and impossible to accept. Once a female high school student said to me: ‘I admire Socrates for accepting his death with philosophical resignation, but I love Christ for dying a human death’. Let us not forget Christ’s cry: ‘My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?’

Job, ‘Dialogus de Laudibus’, 12th Century

The sensitivity that God has to the pain felt by any of His creatures is shared by God’s people, who themselves are pained by anything bad or distressful that happens to God’s creatures. Abba Isaac says: ‘A merciful heart is a heart burning for the sake of the whole of creation – for men, for birds, for animals, for demons, and for every created thing, and by the recollection and sight of them the eyes of the merciful man pour forth abundant tears. From the strong and vehement mercy which grips his heart and from his great compassion, his heart is humbled and he cannot bear to hear or to see any injury or slight sorrow in creation. For this reason he offers up tearful prayer continually even for irrational beasts, for the enemies of the truth and for those who harm him, that they may be protected and receive mercy, and also for reptiles, his heart being full of mercy like that which fills the heart of God’ (Homily 81). Indeed, the compassion that the saints feel for God’s creatures is not a passive sympathy such as Buddhists feel but an active sharing in the pain felt by their fellows. Abba Agathon, for example, wanted to find a leper so that he could give him his own healthy body in exchange for the leper’s sick one.

Ultimately, pain will always remain a mystery, closely connected with man’s boundless freedom. Now this mystery is being only partly revealed and ‘on our behalf’ by others. When our eyes are finally opened, we will see much more clearly.

Let us stand by each of our suffering brothers with respect and attention and brotherly love and understanding, and let us ask our Crucified Lord to give us Grace, enlightenment and strength to face whatever kind of pain His love allows us to suffer in our earthly lives, on our way to heaven.