Alaska – Majesty & Hardship: the Missionaries continue long tradition of serving native Eskimos

13 December 2014 The Russians brought them both eternal life and temporal death: death in the bottle of vodka and true life in the Orthodox Christian Gospel.

The Russians brought them both eternal life and temporal death: death in the bottle of vodka and true life in the Orthodox Christian Gospel.

To this day, these two extremes continue to coexist, in a rather silent and spiritually violent way, as I witnessed during my two-week pilgrimage and missionary journey in August to the Native Alaskans on Kodiak Island.

A long flight via Dallas and through four time zones brought us to a magical place where, from our airplane windows, we could see massive peaks of snow-covered mountains. A short layover in Anchorage and an hour hop on a prop plane, and we arrived at North America’s Emerald Isle: Kodiak. After 11 p.m., it was still broad daylight. We stayed at St. Herman’s Orthodox Seminary, just next door to the beautiful log-cabin Russian-style chapel. From there, on our first day, we saw Spruce Island across the bay.

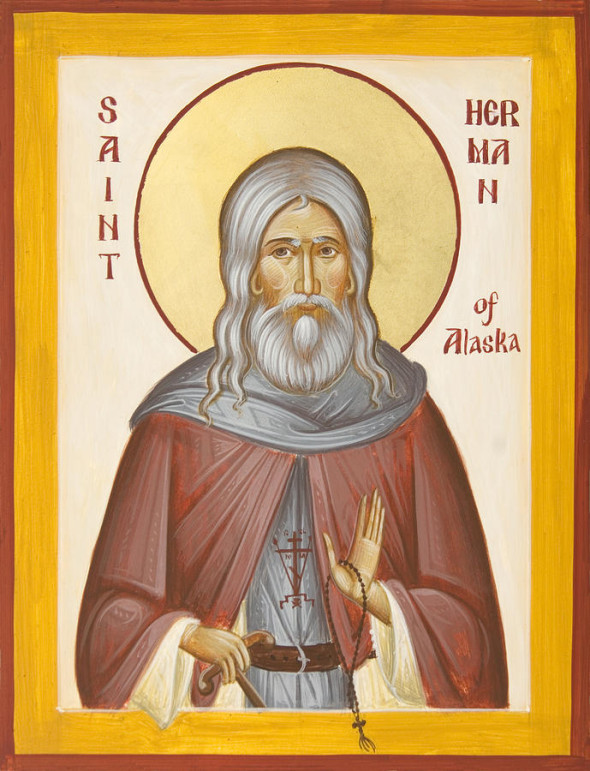

It’s the very island where St. Herman, the Elder and Wonderworker of Alaska, lived and served as the first Russian Orthodox missionary to visit the Native Alaskan Eskimos. We would later venerate his relics – his myrrh-fragrant bones – in the cathedral in Kodiak, and I would have the honor to serve Divine Liturgy (Holy Communion) over his grave on Spruce Island.

Saint Herman of Alaska. Icon by hand of Julia Bridget Hayes

We were a group of 17 who had arrived from across the U.S., and who had come together to offer a youth camp for a week in remote Old Harbor. After Sunday service in Holy Resurrection Cathedral, the first Orthodox parish founded in North America(1794), we packed our bags and headed to the airport again.

Old Harbor, the first Alaskan village to receive Orthodox Christianity, is accessible only by air or water. We traveled on a tiny two-prop plane, each of us carefully weighed to balance the aircraft. For 28 minutes, we flew just a few hundred feet above the 2,000-foot emerald mountains, which appeared as gigantic putting greens.

We descended between twin peaks to land on the gravel runway in Old Harbor, the same gravel that dusted all of the three miles of roads in this sustenance-based fishing village of 220 residents.

We threw our gear into the back of a small bus and drove a mile to the church, passing the harbor hosting a fleet of fishing vessels and guarded by two bald eagles on channel markers and a lagoon not 4 feet deep and filled with sapphire-clear water.

Beautiful & ravaged

Three Saints Church, named for three of the greatest Christian teachers, Saints Basil the Great, Gregory the Theologian and John Chrysostom, is named also for the bay in which the Russian Orthodox missionaries landed in 1794, and for their ship. The present structure, built in the 1950s, along with two houses, survived at least one massive tidal wave in the 1960s. Everything else in the village is new since then, most of the homes being temporary government housing.

For a week, we each lived with families in the village, walking daily to church for services and to the senior center for meals and camp activities. Our main efforts were to be loving friends and companions in the Way, to a few hundred people, many of whom had never been out of the village except for hospital visits, which require a flight since there is only a basic clinic in Old Harbor.

Our work with the children was splendid. A few dozen of the 30-plus children of the village came regularly for our instruction, crafts, games and hanging out. For many, their youthful innocence masked a home life wrecked daily by the ravages of alcohol and drug addiction, or physical or emotional abuse. Sadly, this is more the norm than the exception, according to Fr. Gregory Parker, the village priest and coordinator of the island’s substance abuse program.

Other youths also joined us regularly, also all smiles, but it seemed they were carefully and barely covering deep inner sadness. Some young teens already are acquainted with rehab, miscarriage and addiction, the priest said.

The stable life of the most ancient and unchanged Christianity, transmitted through Russian Orthodox missionaries, meets daily the depressing inter- and transgenerational effects of sin and the bottle brought by Russian fur traders. Life is complicated.

The village is a paradox, depressing and spectacular. Being only three miles long and with residents whose relatives span the generations, no one asks directions, for everyone knows the way. Few use the store. It is for tourists. Mail comes if the fog permits. And to live requires a fishing boat. Breakfast, lunch and dinner often include salmon, cod or halibut. To the south of the church is the bay. Conditions can change from glassy to a raging sea in a few minutes. To the north of the church is a lush green mountain (with a Hollywood-inspired “Old Harbor” sign) covered with amazing wildflowers, salmon-berries and both newly blazed and time-worn Kodiak bear trails.

One cannot easily imagine the harsh winter — five hours of daylight, plus fog and snow — while standing on the dock on a clear, sunny day (light from 6 a.m. until 1 a.m.).

Sweating it out

Save for a handful of folks, mostly non-natives, the village has been Orthodox Christian since 1794. There is one church: Three Saints. There is one priest, with his family: Fr. Gregory Parker, his wife, Marlene, and their three kids.

There is one Protestant missionary family — nice people, whose generosity is matched only by their conviction that this 200-year-old Christian village is not (acceptably?) Christian. This causes tension — some visible, some unseen.

The villagers are incredibly sweet-natured folk, and as we warmed to one another, they began to bring to us offerings of fresh and smoked salmon and halibut. This means we are friends. We cooked with and for them, and served them meals. They shared with us their stories, their native crafts (like stunningly intricate beading), and their banya.

The banya is perhaps the most native — literally and figuratively — experience. The banya is a steam-bath house, small, like a shed. A front room serves as the “cold room,” where one fully disrobes. The back room boasts a stove made from an oil drum, topped by rocks, onto which one splashes water to make the steam. The meat thermometer poking through the wall regularly registered — no exaggeration — between 350 and 400 degrees. Seated on the floor, same-gender groups take steam and sweat as much as each one can take, then one by one, each removes to the cold room to recover for a few minutes, and then back to the steam. After a third time, the stove cooling, one washes with a small tub of tepid water. Although initially quite self-conscious with uncustomary nudity, one quickly realizes that inAlaska, this is totally normal and routine — plus, one forgets almost everything when in an oven hot enough to bake bread!

In the banya one sweats oneself clean, spiritually and physically. It is also the place of reconciliation, problem-solving, brainstorming and local news, like a 350-degree old barbershop. To be invited on the first night is both an honor and a test: Will you meet us where we are with our customs, and can you handle it? Some locals referred to the high temperatures as a game: “smoke the gussok (the white guy).”

To end this first week of our journey, we had to leave our new friends by way of the same small airstrip and same small plane with the same pilot as the previous Sunday. The difference on departure was the weather: heavy fog and light rain. Much prayer and a very talented pilot brought us safely to Kodiak — the journey this time about 200 feet off the Pacific Ocean the whole way, as we skirted the land to avoid flying in unpredictable mountains with zero visibility.

Live and learn

Before leaving Alaska, we visited Spruce Island, a remarkably silent and holy place and the former home of St. Herman, among the first canonized saints of North America. Monk Herman left Valaam Monastery near St. Petersburg, Russia, in January 1794. Feet, dogsled and a boat got him to Alaska by September that year. It is the longest missionary journey in the history of all Christianity.

Fr. Herman and his companions had the odds against them from the start. Their own countrymen – the fur traders – had lied about what they would provide to the missionaries. There was no promised church, no promised supplies and the traders severely mistreated and abused the native Alaskans in a now-sounds-familiar economic plan.

Herman and his monastic brethren did not come, however, to bring Russia to the natives. Nor did they come for financial gain. Nor to spur the economy. They came to learn the local languages, to serve the people and to bring them the Gospel, and in the context of frozen tundra, frigid weather, and with the use of only hand-made kayaks and other vessels.

Their nurture and protection of and love for the native people often caused friction with the Russian fur traders, which led these single-minded entrepreneurs to level all sorts of false accusations against the monks, according to church literature. Through it all, Herman continued to serve the Native Alaskans with love and devotion, including through devastating plagues in which hundreds died at once. Herman devoutly buried the dead and then cared for the orphans with a school and home-grown orphanage.

Our small work in Alaska was a humble contribution to a work of love that has been going on for over 200 years. Technology has changed, to be sure. High-tech fishing fleets have replaced skin-covered kayaks.

But the intersection of faith, government, economy and the routine drudgery of daily life continues to manifest itself there in Alaska, sometimes for better, sometimes for worse.

BY FR. JOHN PARKER This article was published as a special to The Post and Courier in Charleston, SC on Sunday October 9, 2011 and is posted here with permission.