Building bridges: Interfaith Dialogue, Ecological Awareness, and Culture of Solidarity

12 February 2015ADDRESS

By His All-Holiness Ecumenical Patriarch Bartholomew

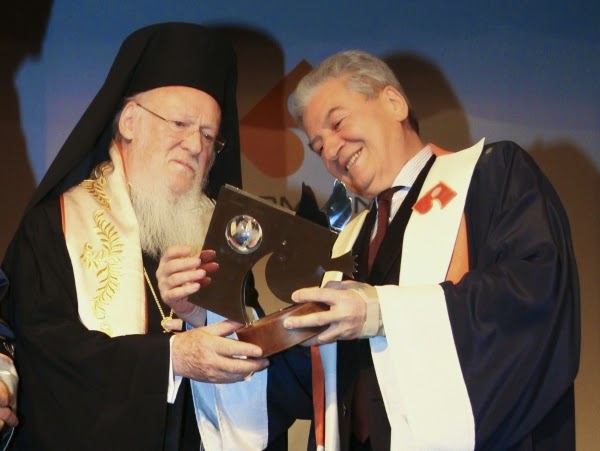

At the Conferral of an Honorary Doctorate in Sociology

From the Izmir University of Economics

(February 9, 2015)

BUILDING BRIDGES

Interfaith Dialogue, Ecological Awareness, and Culture of Solidarity

Eminent Rector, Professor Oğuz Esen,

Esteemed Faculty of Izmir University of Economics,

Distinguished clergy, honorable diplomats and precious audience,

Beloved students, ladies and gentlemen,

Introduction

It is a unique pleasure and a great privilege to receive an honorary doctorate from the Izmir University of Economics. You are an institution that is both young and vibrant, with creativity and productivity, committed to making a difference in our country and in the world, but also dedicated to preserving and promoting the legacy of the foremost statesman and first president of the Republic of Turkey, Kemal Atatürk. We therefore express our wholehearted gratitude to the administration of this university, and in particular to its Rector, Dr. Oğuz Esen, and also to the school’s administration, faculty and students, but above all to Mr. Ekrem Demirtaş, our dearest friend.

We accept this generous distinction in the name of the Ecumenical Patriarchate, which is devoted to the areas of interfaith dialogue, ecological awareness and the culture of solidarity. Our Church has traditionally sought to build bridges between diverse faiths, cultures and peoples, between humanity and the natural environment, as well as to promote peace and solidarity in the name of God and for the sake of the human person.

2. The four functions of religion

A sign of the times at the beginning of this new millennium is “the return of God”, the reevaluation of the role and function of religion. The modernistic expectation of a “post-religious secular age” is replaced by talk of a “post-secular period” or even of a “religious explosion”.

Religion appears as a central dimension of human life, both at the personal and the social levels. It claims a public role and it participates in all central contemporary discourses. Without reference to religion, it is impossible to understand the past, to analyze the present, or to imagine the future of humanity.

The crucial functions of religion are evident at the following four areas of the human existence and co-existence:

- Religion is connected with the deep concerns of the human being. It provides answers to crucial existential questions, which permanently affect the human soul. It gives orientation and meaning of life. This is why negligence or oppression of religiousness results in various alienations in human life.

- Religion is related to the identity of peoples and civilizations, a fact which has definitely been obvious after the fall of the “iron curtain” in 1989. Systematic atheistic ideology and indoctrination failed to uproot religious identity, which constitutes the core of cultural identity. This is why, knowledge of the belief and the religion of the other is an indispensable precondition of understanding otherness and of the establishment of communication and dialogue.

- Religions have created and preserved the greatest cultural achievements of mankind, essential moral values, and respect of human dignity and of the whole creation. The sacred texts of the religions include precious anthropological knowledge. Religion is the arc of wisdom and of the spiritual inheritance of humanity. Culture has in general the stamp of religion. Even modern humanistic secular movements, for example the human rights-movement, cannot be understood and evaluated independently of their religious roots.

- The fourth essential function of religion is peacemaking. Religions constitute central factors in peace processes. Hans Kűng puts forward that peace between religions is the main precondition for peace between peoples and civilizations, for universal peace. Religions can, of course, divide; they can cause intolerance and violence. But this is their failure, not their essence, which is the protection of human dignity. The revival of religions -if that were a regeneration and expression of their genuine elements- was always related to a contribution to reconciliation and peace. In our times, the credibility of religions depends largely on their commitment to peace. The way to peace and reconciliation is interreligious dialogue and cooperation in view of the main contemporary challenges, like the destruction of the natural environment and the growing economic and social crisis.

Our world is in crisis, indeed. Yet, never before in history have human beings had the opportunity to bring so many positive changes to so many people and to the global community simply through encounter and dialogue. While it may be true that this is a time of crisis, it must equally be underlined that there has also never been greater chances for communication, cooperation and dialogue.

Let us explore three distinct areas of this task:

- Building Bridges with other Faiths

- Building Bridges with Nature

- Building Bridges of Solidarity

- Building Bridges with other Faiths

There is a symbolical mosaic that adorns the foyer at the entrance to the headquarters of our Patriarchate in Istanbul. It silently represents a decisive moment in the rich and complex story of a city and a state where Christians and Muslims have coexisted over the centuries. This magnificent image depicts Gennadios Scholarios (1405-1472), first Rum Patriarch of the Ottoman period, with hand outstretched, receiving from the Sultan Mehmet II the “firman” or legal document guaranteeing the continuation and protection of the Orthodox Church. It is a symbol of the beginnings of a long coexistence and interfaith commitment.

The Ecumenical Patriarchate has always been convinced of its responsibility for rapprochement and dialogue. This inspires its tireless efforts for unity among Orthodox Churches throughout the world as well as its pioneering efforts for ecumenical dialogue. All of you will be aware of our meetings during this past year with Pope Francis: In May, we met in Jerusalem to commemorate the historical meeting there of Patriarch Athenagoras and Pope Paul VI in 1964; in June, we accepted the invitation of the Pope to join him in a prayer for peace at the Vatican in the presence of President Peres of Israel and President Abbas of Palestine; and in November, His Holiness accepted our invitation to attend the patronal feast of our Church in Phanar, Istanbul.

However, even at the cost of defamation for “ecumenistic” or “syncretistic” choices, we have never restricted such engagements. The Ecumenical Patriarchate has always labored to serve as a bridge between Christians, Muslims, and Jews. Since 1977, it has pioneered bilateral inter-religious dialogue with the Jewish community (on such topics as law and social justice); since 1986, it has initiated bilateral interfaith dialogue with Islam (on such matters as peace and pluralism); and since 1994, it has organized international multi-faith gatherings for deeper conversations between Christians, Jews and Muslims (on such issues as respect and tolerance). We continue these efforts with sincerity and confidence.

As a young boy, we remember seeing the then Ecumenical Patriarch Athenagoras, an extraordinary leader of profound vision and ecumenical sensitivity. He was a tall man, with piercing eyes and a very long, white beard. Patriarch Athenagoras was known to resolve conflict by inviting the embattled parties to meet, saying to them: “Come, let us look one another in the eyes.” This notion of “looking at each other in the eyes” honestly, in order to understand and cooperate with one another, is both inspiring and critical for contemporary concepts of intercultural and interfaith dialogue.

Of course, some people have strong convictions that they would rather sacrifice their lives than change their views. Others -we might say fundamentalists- are unfortunately even willing to take the lives of innocent victims to defend these views. This is why we are obliged to listen more carefully, “look at one another” more deeply “in the eyes.” For, in the final analysis, we are always closer to one another in more ways than we are distant from or different to one another. We share far more with each other and resemble one another far more as human beings than we differ in terms of culture and religion. A human being, which grounds its identity exclusively on belonging to a nation and not on being a member of humanity (namely, on the fact that it is human), this creature “has not been really born as a human being”, according to Eric Fromm.

As communities, we are called to face the problems of our world with new eyes. We must constantly pursue alternative ways to order human affairs. We must persistently proclaim ways that reject war and violence, and instead strive for tolerance and peace. Conflict may be inevitable in our world; but war and violence are certainly not. Human perfection may be unattainable in this life, but peace is definitely not impossible. If this century will be remembered, it may be for those who sincerely dedicated themselves to the cause of peace.

The pursuit, however, of peace calls for a radical reversal of what has become the normative and defensive way of survival in our world. Peace does not result from economic and cultural development, from the progress of science and technology, from high living standards. Peace is always a duty; it requires vision, commitment, struggle, sacrifice and patience.

We believe that in the great religious traditions there are potentials and inexhaustible reserves of peacemaking. Yet, being able is not enough. We have to work and cooperate for peace; we have to become effective factors of human progress.

3. Building Bridges with Nature

One of our most passionate concerns during our ministry as Patriarch has been protecting the natural environment, raising ecological awareness across academic disciplines, ecological movements and political governments, as well as advocating for a change in established lifestyles in order that people might become more sensitive to the irreversible destruction that threatens the natural environment today.

Orthodoxy is committed to ecology; it is the “green” Church par excellence. Our faith and our worship strengthen our commitment for the protection of creation and promote the “eucharistic use” of the world, the solidarity with creation. The Orthodox Christian attitude is the opposite of the instrumentalisation and exploitation of the world.

We believe that the roots of the environmental crisis are not primarily economic or political, nor technological, but profoundly and essentially religious, spiritual and moral. This is because it is a crisis about and within the human heart. The ecological crisis reflects an anthropological impasse, the spiritual crisis of contemporary man and contradictions of his rationalism, the titanism of his self-deification, the arrogance of his science and technology, the greed of his possessiveness (“the priority of having”), his individual and social eudaemonism.

For Orthodoxy, sin has a cosmological dimension and impact. The theology of the Orthodox Church recognizes the natural creation as inseparable from the identity and destiny of humanity, inasmuch as every human action leaves a lasting imprint on the body of the earth. Moreover, human attitudes and behavior towards creation directly impact on and reflect human attitudes and behavior toward other people, especially the poor. Ecology is inevitably related to sociology and economy, and so all ecological activity is ultimately measured and judged by its effect upon the underprivileged and suffering of our world. The ecological problem is essentially a sociological one.

We are convinced that the theological perspective cannot only discover hidden dimensions of the ecological crisis, but can also reveal possibilities to face and overcome it. What is required of us, at the threshold of the third millennium, is that we overcome the ways in which we looked upon creation in the past, which implied an abusive, domineering attitude toward the natural world. The solution of the ecological problem is not only a matter of science, technology and politics but also, and perhaps primarily, a matter of radical change of mind, of new values, of a new ethos. In Christian theology we use the term metanoia, which means a shift of the mind, a total change of mentality. This is very important, because of the fact that during the last century, a century of immense scientific progress, we experienced the biggest destruction of the natural environment. It seems that scientific knowledge does not reach the depth of our soul and mind. Man knows; and he still continues to act against his knowledge. Knowledge did not cause repentance, but it brought up cynicism and other obsessions.

Our way to the establishment of an ecological culture has to be an ecological one. It is not proper to intend an ecological culture and to make decisions without taking into account their impact on the environment. Religions can contribute essentially to this aim. In the last three decades, the Ecumenical Patriarchate was the protagonist in ecological sensibilisation and action. If there is one thing that we have learned over the last years, it is the way that all of us are intimately and inseparably interconnected with the natural environment. We know now that even the slightest aspect of pollution and climate change on our planet has transparent and tangible implications for the last speck of dust in every corner of our planet.

We are all called to common responsibility for the common good. We must work towards solutions for the challenges that we jointly face.

4. Building Bridges of Solidarity

We are nowadays facing a worldwide economic crisis and its social outcomes on a global scale. We regard this crisis as a “crisis of solidarity”, as an ongoing process of “desolidarization”. Solidarity is the term, which contains the very essence of social ethos, referring to the pillars of freedom, love and justice. It means steadiness in the struggle for a just society, the respect of human dignity beyond any division of social classes. We are convinced that the future of humanity is related to the establishment of the culture of solidarity.

Religions cannot ignore this immense crisis of solidarity. Economic and social problems affect human beings at the center of their life, their freedom and dignity. Religions developed an impressive tradition of philanthropy and solidarity. Even modern adversaries of religion are astonished at the social power and impact of faith.

The famous biblical parable of the Good Samaritan (Luke 10.25-37), describes the spontaneous compassion and support for the suffering person, despite the fact that this person was a foreigner, or even an “enemy”. Christian love is always concrete and personal. Another truth in this parable is expressed in the answer of Jesus to the initial question: “Who is my neighbor?” For Jesus, the truth of love is to become a “neighbor” for everybody who needs our support. In modern terms: if our help can reach people far from us, it is the sense of the commandment of love to support them, to be their brother and sister. In the same parable, we can also detect the call to work for the improvement of the social conditions, which produce need, injustice, poverty and violence. Indeed, religion is not only a matter of personal life and of privacy, but it plays a pivotal role at the level of society.

Our anthropology, our image of the human being and the purpose of its life, defines our attitude toward humanity and social action. If we see the human being as homme machine, we can easily transform the human person into an object. If we regard the human being as a person (prosopon) created “in the image” of God, then our attitude changes. This person-centered anthropology resists the contemporary objectivization of humanity in the name of scientific progress, the modern glorification of the individual as homo clausus; it resists the oppression of human rights in the name of communitarian structures or by totalitarian regimes, as well as the elimination of the dignity and uniqueness of man within the impersonal process of globalization.

The most serious contemporary threat of the culture of solidarity is economism, the fundamentalism of market and profit. We are not qualified economists, but we are convinced that the purpose of economy should be for the service of humankind. The terms economy and ecology have the same etymological root. They contain the Greek word oikos (household). Oikonomia means care or management of our household; oikologia,-ecology- means study, appreciation of our home, keeping our world as oikoumene, as a place where we live and we can live.

We reject “economic reductionism”, the reduction of the human being to homo oeconomicus. We resist the transformation of society in a gigantic market, the subordination of the human person to the tyranny of the needs, of consumerism, the identification of “being” with “having”, of dignity with property. We demand the respect of social parameters in economy, which are the basis for a life in freedom and dignity; we work for the protection of fundamental human rights and for the establishment of justice and peace.

True faith does not release us from our responsibility to the world. On the contrary: it strengthens us to give witness of reconciliation and peace. The tension between our being “in the world” but, at the same time, “not of the world”, provides for our action orientation, sensibility and effectiveness.

Conclusion: The Future as Openness

Interfaith dialogue, environmental awareness and the culture of solidarity are responsibilities that we owe not only to the present generation. Future generations are entitled to a world free from fanaticism and violence, unspoiled by pollution and natural devastation, a society as a place of solidarity.

We hear it often stated that the last two centuries were times of struggle for freedom and equality. This must become an era of fraternity and solidarity. However, this cannot be achieved without the contribution of religion. Thus, we can realize the gravity of the error of those modern thinkers, who underestimated or rejected the religious phenomenon, the fault of those who were blind in front of the dynamism of religion, of the culture it created, of its contribution to peace and its enormous social impact. They have easily but wrongly identified the negative aspects of religion, such as violence in the name of God, with its very essence.

Progressive intellectuals are in a way accused of having indirectly strengthened fundamentalistic excesses in religion, since they downgraded religious faith and practices. Fundamentalistic explosion is often a reaction against an offense of faith.

Dialogue or openness is the antidote to fundamentalism. It is a gesture and source of greater solidarity. Openness to the “other” does not threaten our particular identity. On the contrary, it deepens and enriches it. Openness resists both fanaticism and acceptance of everything, the nihilism of “anything goes”. It affirms plurality and intercultural exchange. Obviously, everything depends on our attitude toward pluralism and otherness. Pluralism is a hopeful chance and a positive challenge. Fear of difference and otherness leads to the enclosure within the boundaries of our particular culture and consequently to fundamentalism.

Another major challenge for religions in our days is the human rights movement. Modern human rights claim to function as fundamental common values, as universal humanistic criterion. If religions approach human rights in a spirit of openness, they will discover part of their own basic principles and core values. In this way, religions can contribute to a deeper understanding of human rights, of their normative elements and of their limits. This attitude gives religions the chance to promote their own traditional ethos in its proper content and to point out the religious dimension of freedom. After all, the history of freedom does not begin with the history of modern human rights.

Dear students of the Izmir University of Economics: Looking into your eyes means drawing encouragement, inspiration and hope for a bright future.

Distinguished Professors: Your sacred task is to transmit to your students the spirit of openness. It is they who shall carry the responsibility for social values, for religion and culture, for freedom and justice, for the respect of otherness, for solidarity with creation and with humanity. Education has to offer the vision of a culture of participation and sharing, of existence as coexistence, of life as communion.

Weremain thankful for this encounter and express once again our gratitude to your University for the exceptional award and the invitation to address you today.

Thank you very much. And God bless you!