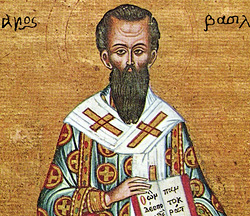

The Theology of Gender – 10. St Basil’s contribution to the canonical tradition

18 April 2017The whole series can be read here: The Theology of Gender

In order to evaluate Saint Basil’s contribution to the canonical tradition and spiritual conscience of the Orthodox Church, we have to consider the following presuppositions: First, the canonical writings of Saint Basil are pastoral works that deal primarily with transgressions and aim at restoring the fallen Christian into communion with the body of the Church. The ultimate goal of the legislator is the salvation of the persons committing the transgression and their discipline in such a way as to lead them to repentance while preventing others from entering similar situations. The penances were warning lessons for the whole Christian community and for society in general. The way that we ought to view these rules should be in the spirit of the soteriological work of the Church and not as mere criminal laws.

In order to evaluate Saint Basil’s contribution to the canonical tradition and spiritual conscience of the Orthodox Church, we have to consider the following presuppositions: First, the canonical writings of Saint Basil are pastoral works that deal primarily with transgressions and aim at restoring the fallen Christian into communion with the body of the Church. The ultimate goal of the legislator is the salvation of the persons committing the transgression and their discipline in such a way as to lead them to repentance while preventing others from entering similar situations. The penances were warning lessons for the whole Christian community and for society in general. The way that we ought to view these rules should be in the spirit of the soteriological work of the Church and not as mere criminal laws.

Second, most of the moral transgressions concerning marriage were also offences in the eyes of civil law, and as such they were treated respectively. The Church distanced herself from the severe regulations of the civil law but in a way that was not contrary to the social ethos, respecting the given cultural establishment. Christianity appeared not as a revolutionary movement that came to overthrow the social order, but as a new way of life with higher moral standards. The respect of Saint Basil for the social establishment is evident in many of his canons, as for example in his eighteenth canon[1] which deals with transgression of a virgin: “it is a great sin for even a slave woman who has given herself up to a clandestine marriage to imbue the house with corruption and roundly insult the owner by her wicked mode of life.”[2]

Finally, the canonical regulations of the Church also served the purpose of preserving the integrity of the Christian communities from the squall of many heresies and deviations from the pure faith. The sixth canon of Saint Basil states: “For this is also advantageous to the Church for safety, and affords heretics no occasion to complain against us on the ground that we are attracting to ourselves on account of our permitting them to sin.” [3]

Having all these in mind we must appreciate the truly orthodox attitude of St. Basil, who balanced faithfulness to the religious and social traditions with grace, forgiveness, and openness of mind. The common theme in his canonical regulations is the persistence on the outcome of the penance, which is the true repentance of the sinner and the restoration of his relationship with God, and not just keeping the letter of the law. For example, he repeats the need for: “adjusting the cure to the manner of repentance”[4], by explaining that “we do not judge these matters in every case with reference to time, but are inclined to pay more attention to the manner of repentance.”[5]

Despite the oppression of women by the social establishment and the respect the Fathers showed towards its practices, St. Basil expresses a genuine respect towards women and their rights as human beings. Thus, in canon 42 he acknowledges the social premise that a woman must be under the authority of her father (or other male guardian from the family), and states: “Marriages entered into without the consent of those in authority are fornications.” [6] Nevertheless, in canon 18 he refuses to accept young women into the order of virgins without taking in consideration their own will, disregarding the will of their father or brothers, who sometimes committed them out of self-interest: “for parents and brothers tender many maidens, and even before they have attained the proper age, not because they have spontaneously striven after a life of celibacy, but because their parents or brothers have been governed by considerations of convenience to themselves, which maidens must not be readily accepted, until we investigate their own mind openly.”[7]

In other instances St. Basil is deeply sensitive and kind towards sinful women: “As for women who have committed adultery and have confessed it out of reverence or because they have been more or less conscience-stricken, our Fathers have forbidden us to publish the fact…but they ordered that such women are to stand without communion until they have completed the term of their penitence.”[8] The adulteress who confesses her sin is to be treated with respect, and the penance is different than the case of an unrepentant adulteress. Though not allowed to receive Holy Communion, she should stand with the faithful in the Liturgy, and not with the other sinners outside, so as not to give rise to suspicions about the nature of her sin.

[1] Canon 18 of St. Basil «Μέγα μέν ἁμάρτημα καί δούλην λαθραίοις γάμοις ἑαυτήν ἐπιδοῦσαν, φθορᾶς άναπλῆσαι τόν οἷκον καί καθυβρίσαι διά τοῦ πονηροῦ βίου τόν κεκτημένον». All canonical texts in Greek are taken from St. Nikodemos the Hagiorite, Πηδάλιον, Ἀκριβής ἀνατύπωσις τῆς γ΄ ἐκδόσεως τοῦ 1864, (Θεσσαλονίκη, 2003) , (hereafter, Πηδάλιον).

[2] All canonical texts in English are taken from The Rudder, Ed. and Trans. By Ralph J. Masterjohn (West Brookfield, MA: Ralph J. Masterjohn and the Orthodox Christian Society, 2005) CD-ROM, (hereafter, The Rudder).

[3]Canon 6 of St. Basil «…τοῖς αἱρετικοῖς οὐ δώσει καθ΄ἡμῶν λαβήν, ὡς διά τήν τοῦ ἁμαρτάνειν ἂδειαν ἐπισπωμένων πρός ἑαυτούς».

[4] Canon 2 of St. Basil «…ὁρίζειν δέ μή χρόνῳ, ἀλλά τρόπῳ τῆς μετανοίας τήν θεραπείαν».

[5] Canon 84 of St. Basil «Οὐ γάρ πάντως τῷ χρόνῳ κρίνομεν τά τοιαῦτα, ἀλλά τῷ τρόπῳ τῆς μετανοίας προσέχομεν».

[6]Canon 42 of St. Basil «Οἱ ἂνευ τῶν κρατούντων γάμοι, πορνεῖαί εἰσιν».

[7] Canon 18 of St. Basil «Πολλάς γάρ γονεῖς προσάγουσι καί ἀδελφοί, καί τῶν προσηκόντων τινές πρό τῆς ἠλικίας, οὐκ οἲκοθεν ὁρμηθείσας πρός ἀγαμίαν, ἀλλά τι βιωτικόν ἑαυτοῖς διοικούμενοι, ἃς οὐ ῥαδίως προσδέχεσθαι δεῖ, ἓως ἂν φανερῶς τήν ἰδίαν αὐτῶν ἐρευνήσωμεν γνώμην».

[8] Canon 34 of St. Basil «τάς μοιχευθείσας γυναῖκας καί ἐξαγορευούσας δι’ εὐλάβειαν, ἢ ὁπωσοῦν ἐλεγχομένας, δημοσιεύειν μέν ἐκώλυσαν οἱ Πατέρες…ἳστασθαι δέ αὐτάς ἂνευ κοινωνίας».

The whole series can be read here: The Theology of Gender