Compulsion and the Church (Luke 14, 16-24)

18 December 2017Although these days it’s claimed that rights and the opportunities for choice are being consolidated, in fact we’re being subjected to harsh coercion and manipulation. Despite the best efforts of many people, the vision of freedom really hasn’t succeeded, and the prevailing reality is one of coercion. In the name of ideas, noble aims, even religions, obligations are being imposed and various forms of violence are being exercised, either by the authorities, who fairly or unfairly invoke their responsibility to do so, or by groups who are seeking authority and invoke their rights to do so, or by those who are opposed to all authority and who invoke the need to come into conflict with it in order to justify their actions. And beyond the authorities, there’s the financial and economic sector, which is a source of coercion and servitude in itself, with its priority of making profits, the right and access to which are not open to all, on the basis or justice and morality, but instead are founded on the law of the jungle. And on the ideological plane, obsessions and stubborn insistence on theories and sets of beliefs, locking in to ill-founded or utopian ideas, the fixations of half-baked knowledge or highly-regulated education, produce and cultivate nothing other than a competitiveness which doesn’t result in dialogue but in a plethora of polarized social positions, which, in turn, bring conflicts, the main aim of which is domination and imposition, to the exclusion of any other party.

We should make special mention here of religions, since there are certain centres of power which artificially cultivate the notion that it’s religions which have played a leading role in coercion and imposition. We need to make it clear that whatever horrific crimes have been committed in the name of whatever god, it is people who are responsible, not commonly those who are real believers, but rather those who exploit religious sentiments for their own purposes, deliberately pursuing secular aims and purposes by adopting some religion or other as an ideology. We should stress that no religion has coercion as a means of dissemination, since even in Islam, jihad or holy war is not one of the five essential pillars of the Muslim faith, but is rather considered to be an exceptional option.

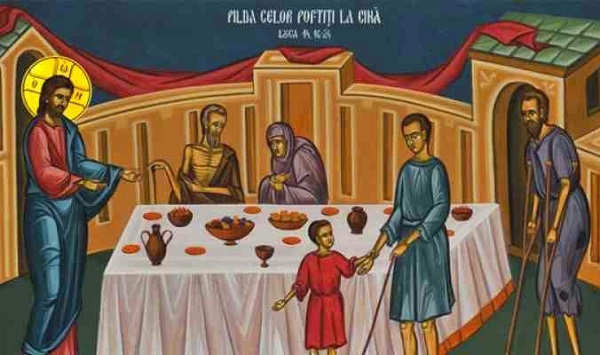

And yet, in the Gospel there’s the exhortation to ‘compel’. It’s in the parable of the great feast. At the beginning there’s a description of the insulting rejection of the householder’s invitation by those he initially considered eminently suitable and therefore more deserving of an invitation. But their involvement with the everyday cares of their life made it impossible for them to realize the honour the man was doing them and they turned their backs on him.

How did the householder react to the refusal of his invitation? According to the Gospel, he was very angry and this emphasizes the responsibility borne by those who reject the invitation extended by our Holy God, especially since they’ve already been given priority. So he tells his servants to go out into the streets and squares and to gather together all those who have been regarded with disdain: the poor, the lame, the sick, and the blind, and to have them come to this important banquet and enjoy what the others were unable to recognize as being for their good and their salvation. And when this process was complete and they could see that there was still plenty of room, the householder again gave orders to one of them to go out into the farther away alleys, to the most forgotten and abandoned people and to compel them to come to the house and enjoy the fine meal.

In connection with the Gospel reading, what does ‘compel’ mean here? Or rather how could one person ‘compel’ all those whom his master had invited? And how is the ‘compel’ linked to the ‘fine banquet’? It’s clear that it means that the lone servant was meant to persuade all those he invited to respond to his request, since it’s likely that they would have refused, either out of awareness of their situation or their natural shyness. How could a poor person, an outcast, a cripple or someone who was fearful have believed that such an invitation was for them, at a place they’ve never even dreamed of finding themselves in? So the job of the servant was to convince them, to overcome their fear, their reluctance and their wariness.

And that’s the way the Church treats us today. It doesn’t manipulate or coerce us. In any case, how could it in a secular environment where any reference to matters of the faith at best attracts ironic smiles if not insulting responses? But even in the past, when the Church was thought to be ‘established’, when did it ever force people? When did it bind them? When did it coerce them? With the weapons of preaching and prayer, the Church asks the Holy Spirit to illumine us, so that we can embrace the truth and live in accordance with it.

Yet there are features of our faith which might be thought of as pressuring us towards taking a conscious spiritual course. If you think of the redemptive sacrifice of the Lord, His voluntary death, the sublime nature of the Cross, how can you not be moved and not want to respond in kind to this benefaction? If you look at the lives of the saints, see the rivers of blood shed by the martyrs, and the struggles of our ascetics, how can you not want to be like them as far as you can? If you delve into the riches of the texts of the Fathers of the Church and the Holy Tradition which they support, how can you not want to be plunged into them and to be reborn ‘from water and the spirit’?

God’s love knows how to pursue us and imprison us, not in the snares of violence and psychological coercion, but against a background of freedom, spurring our self-esteem, strengthening the voice of our conscience and bringing us holy and unique experiences. How far we choose to respond to all this is, in the end, an indication of what sort of people we are.