Cyprus: from internecine tension to the coup of 1974

13 August 2014The imposition of the dictatorship in Greece on 21 April 1967 brought destabilization and defensive disorganization to Cyprus, while, at the same time, representing a blow to the unity of the [Greek] population. The result was to embolden the Turks in Cyprus and in Turkey.

The arrest of Rauf Denktaş

On 31 October, 1967, one event sparked new tensions: in the Agios Theodoros area of Karpasia, the Turkish Cypriot leader, Rauf Denktaş, was arrested. He had occupied a leading post as prosecutor during the period of British rule, and already represented the hardline section of the Turkish Cypriot population. From 1964, when he fled from Kokkina, Denktaş had been outside Cyprus, since the Cypriot authorities had denied him entry to the island, because of his rebellious actions.

In the cross-examination which followed, Denktaş confessed that he’d come to Cyprus to carry out a mission assigned to him by the Turkish government. He did not expand on the nature of this mission.

In a note, the Turkish government expressed ‘its sadness’ at Denktaş’ illegal entry to the island and submitted a request that he be allowed to stay in the Turkish part or to return to Turkey. Once arrested, he himself also addressed a plea to the government of the Republic that he should not be brought to trial, but instead be sent back to Turkey. In his plea, he appealed to the generous nature of the Cypriot authorities and assured them that he would never again attempt to enter the island illegally. In the end, Denktaş was sent back to Turkey on 12 November, 1967. Naturally his promise wasn’t kept.

The events of Kofinou-Agios Theodoros

In November 1967, the bloody events of Kofinou-Agios Theodoros in the Larnaka region took place. Turkish rebels refused to allow a police patrol from the Cypriot government to enter Agios Theodoros. So, on 14 November 1967, the police took over the village. The next day, when police, accompanied by a section of the National Guard, attempted to remove road-blocks they were subjected to fire from the high ground in the region, which was occupied by Turkish Cypriots. The clashes soon spread and the National Guard occupied Kofinou, using armoured forces and heavy weapons.

In the evening of the same day, the dictatorship in Athens issued an order for Greek forces to withdraw from the occupied area, and this withdrawal took place in the early morning hours of 16 November 1967. It also ordered the immediate recall of the chief of the Cypriot Armed Forces, General George Grivas-Digenis, and this occurred the very same day.

The episode became the occasion for the expression of hostile sentiments in Turkey and the same followed among the Turks in Cyprus. The latter began to fire indiscriminately, improving their positions along the length of the demarcation lines. There were reports of an impending Turkish invasion, and these came from the Cypriot representative at the U.N. Unease deepened when American diplomats and citizens in Cyprus were transferred to Beirut.

The withdrawal of the division

Intense diplomatic activity then took place off-stage and in public, accompanied by significant military movements. The military government in Athens acceded to the demands of the Turkish government and recalled the Greek forces which had been sent to the island in 1964. The reinforced Greek Division began its withdrawal from Cyprus in December 1967, taking its heavy equipment (armoured vehicles, artillery etc.) as well as its special forces charged with repulsing any threat (parachutists and so on). The weakening of the defences of the island had dismal repercussions on the morale of the [Greek] population and, at the same time, gave the Turkish Cypriots the opportunity to regain lost ground and present themselves as a self-reliant entity. Simultaneously, the withdrawal of Greek forces opened the way for the Turkish invasion. The Turkish Foreign Minister, İhsan Çağlayangi, announced in Parliament on 27 December 1967, that ‘the departure of the Greek military from Cyprus has altered the balance of forces’. The immediate consequence of the withdrawal of the Division was the decision by the Turks, on 29 December 1967, to set up the ‘Turkish Administration’, which would later evolve into the pseudo-state.

Internecine tension

In the years which followed, tension and distrust were created among the Greek Cypriots, which were fanned by the Athens dictatorship. Leading the anti-government forces, acting under the name of EOKA B, was General George Grivas, who died suddenly on 27 January 1974. The next day, the President of the Cypriot Republic, Archbishop Makarios, made the following announcement: ‘The death of General George Grivas-Diyenis has moved the Greeks in Cyprus deeply. The general offered valuable services to Cyprus and to the whole of the nation. I often disagreed with General Grivas as regards the method of handling the Cypriot national problem. I am saddened that for two years I have been in continuous disagreement with the general over actions and initiatives in which he was involved. I have never doubted, however, his enormous contribution to the struggle of the Greek Cypriot people, who have given him an outstanding position in history. Greek Cypriots will always honour the memory of General George Grivas-Digenis.’

Internecine tension continued with attacks by groups in towns and the countryside and with the theft of arms from National Guard barracks. From documents and other information which came into the hands of the Cypriot authorities, it can be shown that the dictatorship in Athens was behind the creation of this tension.

The coup

On the morning of 15 July 1974, the Presidential Palace in Lefkosia [Nikosia] was suddenly subjected to a hail of fire from armoured vehicles, which had left the National Guard barracks at Kokkinotrimithia at 8:15 and deployed around the Palace. The President, Archbishop Makarios, was there, receiving the visit of a group of children from Cairo.

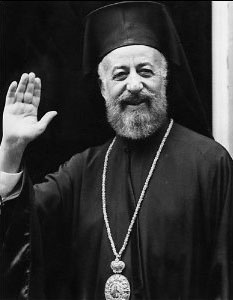

The President of Cyprus, Archbishop Makarios

The Presidential Palace went up in flames. Makarios escaped with three bodyguards, along the bed of a river which had not yet been cut off, and reached the Monastery of Kykkou, where he had begun his career in the Church. From there he went to Paphos where, on a makeshift radio transmitter, he sent out an address which began: ‘Greek Cypriot people. The voice you’re listening to is familiar to you. You know who’s talking to you. It’s me, Makarios. It’s me, who you elected to be your leader. I’m not dead, as the junta in Athens and its representatives here would have liked’**.

A few hours earlier, the rebels, who had taken over the official radio station, had announced that ‘Makarios is dead’.

The coup was met by heroic resistance and self-sacrifice from the Army Reserve, the Presidential Guard, the Security Forces and a host of citizens, who ran to take their place at the side of the legitimate forces of the state. The rebels kept making fierce surprise attacks on pockets of resistance in Lefkosia [Nikosia], Lemesos, Paphos and other places where the democratic reflexes of the Cypriot people were in evidence.

The clashes were bloody and the insurgents, who had mechanised forces and tanks at their disposal, managed in the end to prevail and attain their objectives.

The dictatorship in Athens, in collaboration with its agents in Lefkosia, dubbed the journalist Nikos Sampson ‘President’ of the Cypriot Republic. Curfews were imposed in towns and villages and mass arrests of citizens took place.

The internal front had completely collapsed and the count-down to the invasion had already begun.

*I am aware, as of course you are, that ‘internecine’ means destructive, but since Samuel Johnson got the etymology wrong all those years ago it has come to mean ‘occurring between members of the same country, group, or organization’ (Merriam-Webster), In any case, it seemed preferable to ‘intra-communal’.

** It is certainly true that Britain made serious mistakes in Cyprus and that relations between the country and Makarios were strained, to put it mildly, but, in the interests of fairness, it should be mentioned that it was the British who air-lifted His Beatitude from Paphos to their base in Akrotiri. He remained safe in Britain for five months, meeting the Prime Minister, Harold Wilson, to discuss developments, before returning to Cyprus.