Evangelical Monasticism – Part 4

2 August 2014 Blessed Seraphim of Sarov, the great Russian hesychast of the last [19th] century, said that if you made your peace with God, many people would come to find peace with you. Saint Seraphim was speaking from his personal experience and also from the experience of the long hesychast tradition of the Church. It’s been well observed that the more those Fathers who were at peace in God withdrew into the desert, the more the crowds of people who flocked to them to seek benefit.

Blessed Seraphim of Sarov, the great Russian hesychast of the last [19th] century, said that if you made your peace with God, many people would come to find peace with you. Saint Seraphim was speaking from his personal experience and also from the experience of the long hesychast tradition of the Church. It’s been well observed that the more those Fathers who were at peace in God withdrew into the desert, the more the crowds of people who flocked to them to seek benefit.

In specific instances, monastics are called by the Lord Himself, as was the case with Kosmas Aitolos, to undertake a broader task of preaching and awakening. But it’s always a call from God, never from the self. Could Saint Kosmas really have saved and enlightened the enslaved Greek people if he hadn’t first been enlightened and burnished by twenty years of monastic ascesis, silence, purification and prayer?

Monastics don’t seek to save the world with pastoral or missionary activity, because ‘being poor in spirit’, they take the view that they’re hardly able to save others before they’re saved themselves. They surrender themselves to God without any plans or conditions. They’re always at the Lord’s beck and call, ready to hear His command. The Lord of the Church calls upon the workers in His vineyard to labour in whatever way He thinks will save and benefit them. He called upon Saint Gregory Palamas to undertake the pastoral protection of the people of Thessaloniki and to put into Orthodox terminology the faith of our fathers. He called upon Saint Kosmas to go out and preach and undertake missionary journeys, while He enlightened Saint Nikodimos the Athonite to preach, without ever going out into the world, through his most theological and spiritual writings, which to this day bring so many souls to God. Other monastics have been called to bring benefit to the world through silence and perseverance, through their prayers and tears, as was the case with the Athonite Saint Leontios (Dionysiatis), who, for sixty years, never left his monastery, but remained enclosed in a dark cell. The Lord showed that He had accepted his sacrifice by giving him the gift of prophecy. After his demise, myrrh flowed from his body.

But what mostly makes the blessed monastics the joy and light of the world is that they preserve the ‘the image of God’. In the unnatural situation of sin in which we live, we forget and lose the measure of what it means to be real people. Blessed monastics show us what we were like before the Fall and what deified people are like, that is the image of God. And so monastics are the hope of humankind, at least for those who are able to discern our real and more profound nature without the prejudices of transient ideologies. If people can’t be glorified, and if we haven’t personally met glorified people, it’s difficult to hope in the possibility of overcoming our fallen state and attaining the state for which the good Lord created us, which is joyful glorification. As Saint John of the Ladder says, ‘The angels are the light for monastics; the monastic state is the light for all humankind’ (Discourse XXVI).

Since monastics have the grace of glorification even in this present life, they’re a marker and witness to the world of the Kingdom of God. According to the holy Fathers, the Kingdom of God is the gift of the Holy Spirit dwelling within us. Through glorified monks and nuns, the world knows ‘unwittingly’ and sees ‘invisibly’ the character and glory of the deified human person and of the coming Kingdom of God, which is not of this world.

So, through monasticism, the Church retains the eschatological conscience of the Apostolic Church, keeps alive the expectation of the coming Lord and also His mystical presence among us, the fact that the Kingdom of God is within us.

Remembrance of death and fertile virginity take monastics forward into the future age. As Saint Gregory the Theologian teaches, ‘[Christ] was born from a virgin and made provision for virginity as leading us elsewhere and shortening our worldly existence or, rather, directing us from this world to the next, that is from the present to the future… and he [Basil] convinced people concerning true virginity, turning them from [an appreciation] of external beauty to internal, from actions to that which cannot be seen’. Monastics who are virgins in Christ transcend not only what’s unnatural but even what’s natural and, having reached the supra-natural, they share in the sexless condition of the angels, concerning which the Lord said, ‘For in the resurrection there will be no marrying nor giving in marriage, but they will be like the angels in heaven’ (Matth. 22, 30). Like the angels, monks and nuns remain virgins not in order to obtain practical benefits for the Church (missionary activity) but in order to worship God ‘in their body and spirit’ (I Cor. 6, 20).

According to Saint Gregory of Nyssa’s theology, virginity puts a limit on death, as was the case with Mary, the Mother of God. Death reigned from the time of Adam until her because what happened with her was like a stone dropping on the fruit of virginity and shattering. It is shattered in every soul, in this transient life, through virginity, and its dominion is overthrown, since it has no-one then to sting (On Virginity, xiv, 1, 25, in S.C. vol. 119, p. 426).

The evangelical, eschatological spirit which monasticism preserves also protects the Church in the world from becoming secular and from engaging in sinful situations, which are in opposition to the spirit of the Gospels.

Although silent and isolated in terms of locus, monastics are spiritually and mystically in the midst of the Church and, from a high pulpit, preach the claims of the Lord of All and the need for a completely Christian life. They orientate the world towards Jerusalem above and the glory of the Holy Trinity, as the universal aim of creation.

This is the Apostolic teaching preached authentically, in every era, by monasticism and it requires an apostolic renunciation of everything and a life of the Cross. Like the Holy Apostles, so monastics ‘leave everything behind’, follow Christ and fulfill His word: ‘everyone who has left houses or brothers or sisters or father or mother or children or lands, for my name’s sake, will receive a hundredfold and will inherit eternal life’. ‘Having nothing and owning everything’ they share in the sufferings, deprivations, tribulations, vigils and earthly insecurity of the Holy Apostles.

But, like the Holy Apostles, they are made worthy of becoming ‘eyewitnesses of his majesty’ (2 Peter 1, 16) and of having personal experience of the grace of the Holy Spirit, so that they can say, in apostolic fashion, that ‘Jesus Christ came into the world to save sinners, of whom I am first’ (1 Tim. 1, 15) ,but also ‘what we have heard, what we have seen with our eyes, what we have looked at and touched with our hands, concerning the word of life- this life was revealed and we have seen it and testify to it, and declare to you the eternal life that was with the Father and was manifested to us’ ( 1 John, 1, 1-2).

This vision of God’s glory and Christ’s sweet visitation to monastics justify all their apostolic struggles and make the monastic life ‘real life’ and ‘blessed life’ which they wouldn’t exchange for anything, if any of them have come to know it even for a short time.

Monastics radiate this grace mystically to their brothers and sisters in the world, too, so that everyone can see, can repent, can believe, can be comforted, can rejoice in the Lord and glorify the merciful God ‘who has given such authority to people’ (Matth. 9, 8).

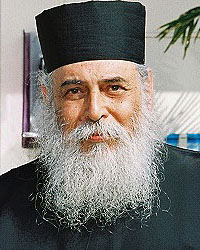

Source: The late Archimandrite George, Abbot of the Holy Monastery of the Blessed Grigoriou, Ευαγγελικός Μοναχισμός, no. 1, pp. 64-80. Published by the Holy Monastery of Blessed Grigoriou, Holy Mountain, 1976.