The Icon as a unique and inimitable fact in the Church

24 August 2014

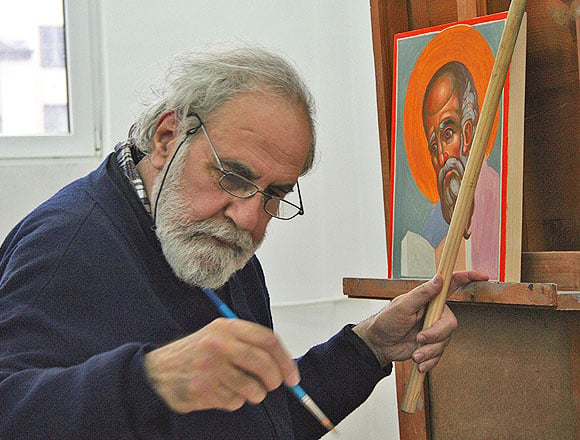

Temple painted by Father Stamatis Skliris

An icon expresses the relationship of history towards the Kingdom of God. Although much of the emphasis focuses upon the Last Times, a necessary feature of the person in the icon is their particular way of life and the relationships in their lives within historical time. This is why the icon reflects the eschatological relationship and the salvation resulting from this in the form of certain specific events which stamped the existence of the persons depicted while they lived in historical time and which lent their mortal existence certain characteristics which remain into eternity. We, see, for example the stigmata of the Lord in the icon of the Resurrection, and the Cross in His halo. Similarly, the saints are depicted ‘bearing the stigmata of their Lord’.

This means that the saving events which took place within history and were elevated by their relationship to the Lord, also acquire the character of something unique and inimitable. For instance, the specific ascetic effort of a saint, which took place at a particular time and place, played a unique role in his or her salvation and, through this, in the life of the Church, in worship, in the icon and in the salvation of each of us as members of the Church. And the demise of the saint, either in peace, through martyrdom or in any other way (in other words their exit from this life and their entry into the Kingdom of Heaven) is a new and unique event for the Church, one through which the whole Church enjoys a foretaste of the last things. By having the icon painted and by reverencing it, the Church creates another event. The wood or wall on which the icon is painted, were formerly neutral in Christological, soteriological and eschatological terms, but now assume the dimensions of a new and unique event, because through them, in a special manner, the Church is linked to the eschatological existence and personality of the saint. In this way we understand what the Fathers wrote in texts and in hymns and what was expressed as a Term [Definition] at the 7th Ecumenical Synod: that through the icon of Christ and those of the saints, creation is sanctified.

Father Stamatis Skliris at work

So we understand why an icon isn’t a symbol or simply a type for the Church, through which the saint is merely symbolized. Rather it’s the unique achievement of ecclesiastical communion, as expressed by the painter, who, in this case, occupies the position of an Evangelist, manifesting in colors and patterns the particular ecclesiastical relationship between saint/Christ/the Father. The fact that this must be made clear in practice lends its execution and construction the sense of a personal ascetic effort and spiritual achievement on the part of the painter. The painter must make every new icon of the saint a way for the Church to enter into a relationship with the saint. So, whereas it would be easy for this relationship to be lost and forgotten (which is typical in human affairs and is, according to the Fathers, a very great failing) the painter ‘creates a memory’ of the saint being celebrated, resisting the pull towards forgetfulness which is a concomitant of created time. This ‘memory’ isn’t simply a sentimental reminder, but participation in the Eucharistic community, in the ‘eternal memory’, that is in the memory of our eternal God and Father, which maintains the saint- and, by extension, every believer- in eternal existence and communion. The Eucharistic community, with its feasts which require their relevant iconography, causes the painter to create an event, the new icon of the saint, through which the community returns once more into a relationship with the eschatological person, the saint.

This is consistent with the tradition of the Greek people [and others] of giving different names to the various icons of the Mother of God; of paying particular honour to each of them in the place with which they are especially associated; of attributing specific miracles- which are new unique events- to each of the; of writing special services related to the particular set of historical circumstances in which the icon was found, painted or worked its miracles; of conducting processions and liturgies for special memories, as is the case in many of the monasteries on the Holy Mountain and many pilgrimage sites outside it.

This explains the true Byzantine iconographical ethos, according to which an iconographer didn’t simply refrain from copying an older icon, but didn’t even copy the ideas of one of his own, if he was painting the same subject for the second, third or umpteenth time. Because clearly he would have believed that every new icon was a new and unique event of communion between the Church and the saint depicted.

This is the more profound reason why we shouldn’t have in our churches, nor venerate, icons that are merely mechanical copies of older ones, whether they’re produced by a printing-shop, or, more recently, from a computer. And, by the same token, it’s not right to paint icons in mechanical imitation of an older model, that is without the iconographer having taken the trouble to participate in the ecclesiastical event through his or her own unique ascetic effort.

Unfortunately, in recent years this sensibility has been lost and the Orthodox ethos has degenerated towards a view that exactly the same pattern must be reproduced, with exactly the same colours, without any personal involvement on the part of the painter. Even if these changes are due to external historical and socio-economic reasons, there’s also an unquestionable theological explanation for them. There’s been a change in Orthodox theology, according to which, in former times, the important thing was the relationship of the community to Christ and therefore that of each individual member to the community. This was a relationship that was expressed primarily in the Divine Eucharist. For this reason, the great Fathers described the veneration of icons as an expression of relative worship, that is worship which, through the icon, put the believer and the community into a relationship with the saint or Christ and, in the end, with God the Father. More recently, however, because of a weakening of the Eucharistic experience, of Eucharistic theology and of the sense of the uniqueness of the events and relationships which were connected within the Eucharistic context, other elements in the icon have been given prominence, such as its symbolism, its moral teaching, its psychological expression and so on.

We need to digress a little here, to emphasize that the freedom of the Byzantines as opposed to the post-Byzantines is not being underlined here in terms of any artistic merit or ability, but as Orthodoxy, in the sense of proper thinking as regards the saints and their icons and of the proper glorification of them through their icons. In other words, what we’re concerned with is identifying the Orthodox theological criterion and not any aesthetic evaluation and comparison of different periods of icon-painting. The Orthodox criterion prevents us from slipping into heretical deviations from Orthodox dogma concerning God’s incarnation, salvation in Christ and the depiction of all of them in our Orthodox icons.

But with the conclusion of this theological interpretation, certain elements have already become apparent for a re-examination of the icon today and for a proposal for a teaching method of iconography which would restore the genuine Orthodox tradition, from which we’ve deviated too often in recent years.

(Fr. Stamatis Skliris, Ενεσόπτρω -εικονολογικά μελετήμαστα, M. P. Grigoris, pp. 98-102).