The Unique Divine Liturgy at Easter in Dachau, in 1945

16 May 2016Every Easter Divine Liturgy is, without doubt, unique. But the one celebrated in 194, in the Nazi concentration camp at Dachau stands out as special in the history of the human race. Just a few days after their liberation by the US Army, on 29 April 1945) hundreds of Orthodox Christian prisoners in the camp gathered to celebrate a very different Easter.

The Dachau concentration camp started functioning in 1933, in a former gunpowder factory. The first prisoners were political opponents of Adolf Hitler, who had become Chancellor of Germany earlier that year. Over the course of its twelve years of existence more than 200,000 prisoners were transported to the camp. Most of them were Christians, of all denominations, both clergy and lay people.

Christ opens the gates of a Hell on earth and brings the prisoners out into freedom Icon from the Russian chapel at Dachau

Countless prisoners died in the camp, while hundreds were forced to participate in the inhuman medical experiments conducted by Dr. Sigmund Rascher. Thousands of prisoners from other camps were also piled into railway wagons and sent to Dachau. The vast majority of these died horrific deaths from starvation, dehydration or exposure to diseases.

When the prisoners reached the camp, they were beaten mercilessly, shorn and stripped of all their personal possessions by the guards. Their life was literally at the mercy of the guards, since the latter were free to kill them any time they deemed it necessary. Punishment for various transgressions awaited them every second of their time there, and these included hanging from hooks for hours on end, high enough so that their feet didn’t touch the ground, beatings, whippings and isolation for days in incredibly small rooms.

‘Works Makes (=Sets You) Free’, the macabre inscription on the camp gates

The humiliations of the prisoners came to an end in the spring of 1945, on 29 April. The testimony of the soldiers is staggering:

‘As we crossed the track and looked back into the cars the most horrible sight I have ever seen (up to that time) met my eyes. The cars were loaded with dead bodies. Most of them were naked and all of them skin and bones. Honest their legs and arms were only a couple of inches around and they had no buttocks at all. Many of the bodies had bullet holes in the back of their heads. (Letter from 1st Lieutenant William Cowling. The full text is available on the Internet).

‘Several hundred yards inside the main gate, we encountered the concentration enclosure, itself. There before us, behind an electrically charged, barbed wire fence, stood a mass of cheering, half-mad men, women and children, waving and shouting with happiness – their liberators had come! The noise was beyond comprehension! Every individual (over 32,000) who could utter a sound, was cheering. Our hearts wept as we saw the tears of happiness fall from their cheeks’. (Lt. Col. Walter Fellenz, 42nd Infantry Division of the US Seventh Army).

One inmate, Gleb Rahr, from Latvia, a member of an anti-Nazi and anti-Bolshevik organization, who had been taken to Dachau just a few days earlier and who, after the war, would teach Russian History at the University of Maryland (he died in 2006), gives another kind of testimony:

‘Naturally, I was ever cognizant of the fact that these momentous events were unfolding during Holy Week. But how could we mark it, other than through our silent, individual prayers? A fellow-prisoner and chief interpreter of the International Prisoner’s Committee, Boris F., paid a visit to my typhus-infested barrack “Block 27” to inform me that efforts were underway in conjunction with the Yugoslav and Greek National Prisoner’s Committees to arrange an Orthodox service for Easter day, May 6th.

There were Orthodox priests, deacons, and a group of monks from Mount Athos among the prisoners. But there were no vestments, no books whatsoever, no icons, no candles, no prosphoras, no wine… Efforts to acquire all these items from the Russian church in Munich failed, as the Americans just could not locate anyone from that parish in the devastated city. Nevertheless, some of the problems could be solved. The approximately four hundred Catholic priests detained in Dachau had been allowed to remain together in one barrack and recite mass every morning before going to work. They offered us Orthodox the use of their prayer room in “Block 26,” which was just across the road from my own “block.”

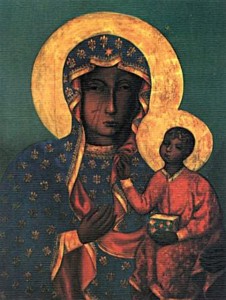

The chapel was bare, save for a wooden table and a Czestochowa icon of the Theotokos hanging on the wall above the table—an icon which had originated in Constantinople and was later brought to Belz in Galicia, where it was subsequently taken from the Orthodox by a Polish king. When the Russian Army drove Napoleon’s troops from Czenstochowa, however, the abbot of the Czenstochowa Monastery gave a copy of the icon to czar Alexander I, who placed it in the Kazan Cathedral in Saint-Petersburg where it was venerated until the Bolshevik seizure of power.

The icon known as the Czestochowa Black Mother of God. According to tradition, it was painted by the hand of Saint Luke the Evangelist. It is considered to be miracle-working and is a national treasure in Poland. The Polish king Vladislav received it from the hands of the Angevins and dedicated it to the Pauline monastery of Jasna Góra

A creative solution to the problem of the vestments was also found. New linen towels were taken from the hospital of our former SS-guards. When sewn together lengthwise, two towels formed an epitrachilion and when sewn together at the ends they became an orarion. Red crosses, originally intended to be worn by the medical personnel of the SS guards, were put on the towel-vestments.

On Easter Sunday, May 6th (April 23rd according to the Church calendar)—which ominously fell that year on Saint George the Victory-Bearer’s Day—Serbs, Greeks and Russians gathered at the Catholic priests’ barracks. Although Russians comprised about 40 percent of the Dachau inmates, only a few managed to attend the service. By that time “repatriation officers” of the special Smersh units had arrived in Dachau by American military planes, and begun the process of erecting new lines of barbed wire for the purpose of isolating Soviet citizens from the rest of the prisoners, which was the first step in preparing them for their eventual forced repatriation.

In the entire history of the Orthodox Church there has probably never been an Easter service like the one at Dachau in 1945. Greek and Serbian priests together with a Serbian deacon wore the make-shift “vestments” over their blue and gray-striped prisoner’s uniforms. Then they began to chant, changing from Greek to Slavonic, and then back again to Greek. The Easter Canon, the Easter Sticheras – everything was recited from memory. The Gospel – “In the beginning was the Word” – also from memory.

And finally, the Homily of Saint John Chrysostom – also from memory. A young Greek monk from the Holy Mountain stood up in front of us and recited it with such infectious enthusiasm that we shall never forget him as long as we live. Saint John Chrysostomos himself seemed to speak through him to us and to the rest of the world as well! Eighteen Orthodox priests and one deacon—most of whom were Serbs—participated in this unforgettable service. Like the sick man who had been lowered through the roof of a house and placed in front of the feet of Christ the Savior, the Greek Archimandrite Meletios was carried on a stretcher into the chapel, where he remained prostrate for the duration of the service.

Other prisoners at Dachau included the recently canonized Bishop Nikolai Velimirovich, who later became the first administrator of the Serbian Orthodox Church in the US and Canada; and the Very Reverend Archimandrite Dionysios, who after the war was made Metropolitan of Trikkis and Stagon in Greece.

Fr. Dionysios had been arrested in 1942 for giving asylum to an English officer fleeing the Nazis. He was tortured for not revealing the names of others involved in aiding Allied soldiers and was then imprisoned for eighteen months in Thessalonica before being transferred to Dachau. During his two years at Dachau, he witnessed Nazi atrocities and suffered greatly himself. He recorded many harrowing experiences in his book Ieroi Palmoi. Among these were regular marches to the firing squad, where he would be spared at the last moment, ridiculed, and then returned to the destitution of the prisoners’ block.

After the liberation, Fr. Dionysios helped the Allies to relocate former Dachau inmates and to bring some normalcy to their disrupted lives. Before his death, Metropolitan Dionysios returned to Dachau from Greece and celebrated the first peacetime Orthodox Liturgy there. Writing in 1949, Fr. Dionysios remembered Pascha 1945 in these words:

‘In the open air, behind the shanty, the Orthodox gather together, Greeks and Serbs. In the center, both priests, the Serb and the Greek. They aren’t wearing golden vestments. They don’t even have cassocks. No tapers, no service books in their hands. But now they don’t need external, material lights to hymn the joy. The souls of all are aflame, swimming in light.

Blessed is our God. My little paper-bound New Testament has come into its glory. We chant “Christ is Risen” many times, and its echo reverberates everywhere and sanctifies this place.

Hitler’s Germany, the tragic symbol of the world without Christ, no longer exists. And the hymn of the life of faith was going up from all the souls; the life that proceeds buoyantly toward the Crucified One of the verdant hill of Stein’.

On April 29, 1995 – the fiftieth anniversary of the liberation of Dachau – the Russian Orthodox Memorial Chapel of Dachau was consecrated. Dedicated to the Resurrection of Christ, the chapel holds an icon depicting angels opening the gates of the concentration camp and Christ Himself leading the prisoners to freedom.

On April 29, 1995 – the fiftieth anniversary of the liberation of Dachau – the Russian Orthodox Memorial Chapel of Dachau was consecrated. Dedicated to the Resurrection of Christ, the chapel holds an icon depicting angels opening the gates of the concentration camp and Christ Himself leading the prisoners to freedom.

The simple wooden block conical architecture of the chapel is representative of the traditional funeral chapels of the Russian North. The sections of the chapel were constructed by experienced craftsmen in the Vladimir region of Russia, and assembled in Dachau by veterans of the Western Group of Russian Forces just before their departure from Germany in 1994. The priests who participated in the 1945 Paschal Liturgy are commemorated at every service held in the chapel, along with all Orthodox Christians who lost their lives ‘at this place, or at another place of torture’.