Apostle James, the Brother of our Lord, First Bishop of Jerusalem

23 October 2016Saint James was the son of Joseph the Betrothed from his (first) marriage. He was blessed by God while he was still in his mother’s womb and was so righteous in his life that all the Jews called him the “Just”. Even from a very early age, James lived a very ascetic life. He did not partake of wine or other strong drinks. In imitation of Saint John the Baptist, he never ate anything that had had the breath of life within it. He never shaved his head, as the Law ordains for those who devote themselves to God (Num. 6, 5). He never washed his hair nor was he anointed with oil, since he cared more for the state of his soul than of his body.

Saint James, the Brother of our Lord, Venetian Icon, 1683

After the Lord’s Ascension, the Apostles unanimously elected James the Just as first bishop of Jerusalem. Perfect in all the virtues of action and contemplation, James alone entered the Holy of Holies of the New Testament- not once a year, like the High Priest of the Jews- but on a daily basis, in order to celebrate the holy sacraments. Dressed in a linen garment, he would enter the Temple and kneel for hours, praying for the people and the salvation of the world, to such an extent that his knees became hard as stone. He presided over the Apostolic Synod which discussed the question of whether Gentiles who adopted the Christian faith should be circumcised. He suggested that they should not be burdened with the ordinances of the old Law, but should be told to refrain from fornication and the consumption of food sacrificed to idols (Acts 15, 20).

In about the year 62, Judea was in turmoil and anarchy after the death of the governor, Festus. The Jews, who had been foiled in their efforts to have Paul put to death (Acts 25, 26), turned their attentions to James, whose fame as a just man had people believing in his teaching. Many people, ordinary and prominent citizens, had embraced the faith and the scribes and Pharisees were afraid that soon everyone would recognize the Messiah in the person of Christ. So they presented themselves to the Bishop of Jerusalem and entreated him to speak to the crowds at the temple. To make himself heard, he went up onto a roof, and preached that Jesus is the Messiah and the Son of God. The scribes and Pharisees were enraged and hurled him from the roof. Despite the fall, he was not killed, and, like Christ before him, prayed for his enemies, until he was stoned and a bystander hit him on the head with a large piece of wood and despatched him. He may have been buried at the site, near the Temple.

The martyrdon of Saint James, fresco, Monastery of Dionysiou, 1547, Holy Mountain Athos

Such was his standing among the people that even the most sceptical Jews considered the manner in which he was put to death to be the cause of the siege and destruction of Jerusalem in the year 70.

The above account is an abridgement of the information provided in the synaxarion. There are a number of points of interest .

The first is the obvious similarity with John the Baptist. Both were dedicated to God from an early age and may have been Nazirites. They were popular among the people for their virtuous lives and personalities. Both were outspoken in the face of official pressure and both were killed because they represented a threat to the establishment.

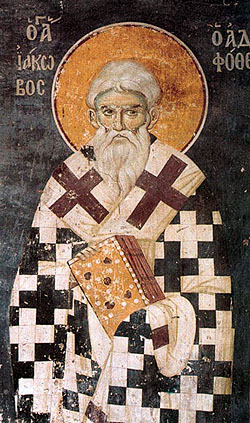

Saint James, 14th Century fresco by hand of Emmanuel Panselinos, Church of Protaton, Holy Mountain Athos

Another similarity is with Saint Paul. It is interesting that both James and Paul, who were both steeped in Jewish tradition and law, to the extent that we might expect them to have been died-in-the-wool hard-liners, should have been the so “lenient” towards Gentile converts (Acts 15, 20). This is often the way of things: those who are “pharisaical” in their approach to, say, the holy canons stick to the letter of the law, whereas those with a deeper insight look for the spirit. As Elder Païsios of the Holy Mountain used to say: “The canons (rules) shouldn’t be canons (guns) to shoot people with”. And, of course, the more flexible approach is only possible from people who have already proved, as Saints Paul and James did, that they were prepared and able to live strictly in accordance with the rules they are prepared to relax for others.

A fuller account of the life of Saint James can be found in the Δωδεκάβιβλος (Twelve Books, pp. 35-43, Rigopoulos editions) by Dositheos Notaras, Patriarch of Jerusalem. Dositheos, who had been consecrated Bishop of Caesarea in Palestine on Saint James’ day, 1666, was writing in the 17th century, but he draws upon much earlier sources, including Eusebius (born ca. 260 and author of the Ecclesiastical History) and Clement the Alexandrian (born ca. 150). His account also includes mention of the fact that James may have been buried on the Mount of Olives.

In recent years, interest has been aroused by the presentation in 2002 of the “James ossuary”, a 2,000-year old chalk box that was used for containing the bones of the dead. The ossuary came from the Silwan area in the Kidron Valley, southeast of the Temple Mount. The first-century origin of the ossuary is not in question, since the only time that Jews were buried in that fashion was from approximately 20 BC to the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 AD. The dispute centres on the date of origin of the inscription. The Aramaic inscription: Ya’akov bar-Yosef akhui diYeshua (“James, son of Joseph, brother of Jesus”) is cut into one side of the box. Scholarly opinion remains divided as to whether the inscription dates from the same time as the box or is a later addition, perhaps even a forgery.

By the same token, for a time many scholars did not consider the epistle and liturgy attributed to Saint James to be “genuine”. G.A. Wells (The Jesus of Early Christians. London: Pemberton, 1971, p. 152), for example, argues that the arrangements for the healing of the sick in James’ epistle, which form the basis of the Office of Holy Unction, indicate a departure from early practice, so the letter belongs to a later date. Similarly, the date and authorship of the Liturgy of Saint James is disputed by some. Dositheos, however, insists that James was Bishop of Rome for twenty-nine years (He specifically rejects 26, 28 or 30 years). During this time, the church must, of necessity, have become more organized. It is far from unlikely that James left behind a summary of his teaching; that he made arrangements for church ministers to perform healing services; and that he supervised the evolution of divine worship in Jerusalem, where his Liturgy is still celebrated regularly. Whether he actually put stylus to papyrus himself, or whether his efforts were later added to by others, it is probably entirely appropriate to ascribe the initial impetus to the Brother of Our Lord.

Hymn:

As the Lord’s disciple, righteous one, you received the Gospel; as martyr you have steadfastness, as the Lord’s brother, boldness of speech; as bishop, the power of prayer. Intercede with Christ our God, that our souls may be saved.