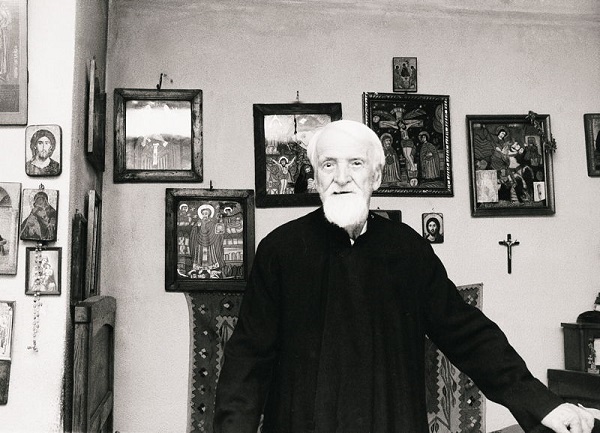

Father Dumitru Stăniloae (1903-1993)

11 February 2017Theologising in the spirit of the Fathers

‘My theology springs partly from the constant and authentic dialogue I have with the Holy Fathers of the Church and partly from my lively and regular dialogue with the triune God, through prayer and liturgical life in my traditional Church, together with my dear Romanian brothers and my Christian brothers everywhere.’

Fr. Dumitru Stăniloae

Father Dumitru Stăniloae’s life spanned almost the whole of the twentieth century. He was born on 17 November 1903 in a village near Braşov in the Transylvanian mountains, to peasant parents, simple people who were deeply rooted in the Orthodox Christian tradition. Both had Biblical names: Irimie (Jeremiah) and Rebeca. His mother was a very dynamic and religious woman, and had great love for everyone. She wanted her son Dumitru to become a priest at all costs. Dumitru’s father was the epitome of the wise peasant, a man who spoke little but always said great things.

Church life in the village and academic theology

In his village Father Dumitru discovered and experienced a typical form of church life, one that was identified with the general life of this small community. ‘The whole of our village’s life was organised around the church…social life was closely bound up with religious life. Since then I have not been able to imagine social life without the Church. The church was very close to the people and the people were completely devoted to the worship life of the church… I grew up in this environment. A church that was very important and lay at the heart of everyone’s lives. The people’s lives were moulded around the church. Even today I am inspired by the life that my family, the village and the people in general led,’ wrote Father Dumitru towards the end of his life.

An important turning-point in Father Dumitru’s life was his choice of academic discipline. He himself wanted to study philosophy so that he could go on to study scholastics. ‘I didn’t know what scholastics was,’ he would write later, ‘I thought it was a grand form of philosophy’. His mother and an uncle of his, who was a priest, persuaded him to study theology at the then famous Theological School in Cernui, which was modelled on contemporary German theological schools. The first thing that Father Dumitru discovered was that there was a huge gulf between academic theology and the kind of church life he experienced in his village. He wondered how, on returning to his village, he would be able to convey academic definitions of God and metaphysical terminology to ordinary people. A second question that arose in his mind concerned a kind of theological completeness which, while confined to the intellectual level, took the form of a full knowledge of God: ‘After studying the theological manuals and learning Bible passages and doctrinal definitions, the theology student felt that he had attained a full knowledge of God, that everything had been said and there was nothing new to add to all this knowledge’.

His first reaction was a certain feeling of disdain for popular piety. A year later, somewhat disillusioned, he left the Theological School and went to Bucharest to study philosophy and philology. A chance, or rather providential, meeting in Bucharest with Metropolitan Nicolae Balan compelled him to return to the Theological School, from which he graduated in 1927 with the sole benefit of ‘having learned how to work methodically and how to study things in depth’.

His encounter with the Greek language

Following Father Dumitru’s persistent requests, the same Metropolitan sent him to Athens for a year on a scholarship. ‘I wanted to find the authentic source and expression of Orthodox theology and felt that I would find it in the Greek Fathers’, he wrote later. Although he stayed in Athens for less than a year, Father Dumitru managed to learn Greek and prepare his doctoral thesis on ‘The Life and Work of Patriarch Dositheos of Jerusalem and his Relations with the Romanian Lands’, which he submitted at Cernui in the autumn of 1928. His brief stay in Athens was to prove an important landmark in his theological career. His greatest gain was learning the Greek language, which had enabled and motivated him to become acquainted with the Church Fathers. In the foreword to the Greek translation of the Introduction to Dogmatic Theology he wrote: ‘I thank God that he has enabled me, in this way, to discharge at least a small part of my sacred debt to the Greek language, to which I owe a great deal. The Greek language, which I learned in Athens sixty years ago and which I have constantly improved, enabled me from the beginning of my theological ministry to maintain a lively and constant dialogue with the Greek Church Fathers’. At the Theological School in Athens, as at Cernui, he found the same kind of theology – one that was influenced by German systematic theology.

His encounter with the Church Fathers through the personality and work of St. Gregory Palamas

In November 1928 he left for Germany, where, again with a scholarship from Metropolitan Nicolae, he continued his studies, first in Munich and then later in Berlin, where he became interested in general church history and particularly in Byzantine studies. While he was in the West he discovered the great Father and Teacher of Orthodoxy, who was to give him the key to understanding and exploring the field of living theology, a development that was to mark all of his theological thinking and his output as a writer. His name was Gregory Palamas. Father Dumitru came to make this discovery through his study of Byzantine history, which inevitably brought the great Church Father to his attention. He searched for manuscripts of Palamas’s works and found them in the National Library in Paris, where he spent his vacations. Every day, for two whole months, he read and copied Palamite texts.

He completed his postgraduate studies in just two years. On 1 September 1929 Metropolitan Nicolae appointed him Associate Professor of Dogmatics at the Theological Academy in Sibiu. He was twenty-six years old. He taught dogmatics for seventeen years (1929-1936) and the following subjects at various other times: apologetics (1929-1932, 1936-1937), pastoral studies (1932-1936) and Greek language (1929-1934). In 1935 he was elected a full professor and in 1936 dean of the Theological Academy in Sibiu, a post he held until 1946, when he was forced for political reasons to move to Bucharest.

For the first year at Sibiu and for his classes in dogmatic theology he translated the well-known manual of dogmatic theology by the Greek theologian Christos Androutsos, which did not entirely satisfy him, as he declared later: ‘I read in Androutsos that there could be no more progress in acquiring knowledge of God, that everything had been said and expressed in the doctrinal definitions and formulas’.

It was then that he decided to translate the Palamite texts that he had brought with him from Paris. Thus began the extremely fruitful endeavour of translating original Greek works into the Romanian language, an endeavour that lasted for the rest of his life and took in the most important works of the Greek Fathers. These translation endeavours were accompanied by constant commentaries and studies on patristic thought and theology, driven by a need to reveal their relevance to the problems faced by modern man. While translating Palamas’s works, he produced his first study on Palamite theology, On the Way of Attaining Divine Light According to St. Gregory Palamas, which was published in the Theological Academy’s yearbook in 1930 (p. 572). It should be remembered that this happened at a time when even in Orthodox circles there were grave reservations about the hesychasm and teachings of Gregory Palamas. As a first-year student, he had read in a book on Byzantine history by a Romanian professor ‘about the strange notion held by Gregory Palamas that certain monks could see the divine light’.

Next followed the translation and publication of two Palamite treatises in the same yearbook: In Defence of the Holy Hesychasts, accompanied by a copious commentary (1931/1932, pp. 5-70). His research on the personality and work of St. Gregory Palamas continued for a long time afterwards and culminated in a scientific monograph dedicated to the great champion and exegete of Orthodoxy and his first patristic teacher. In 1938 The Life and Teaching of St. Gregory Palamas (250 pp.) was published in Sibiu, together with the translations of three new Palamite treatises (160 pp.). If we exclude the book on Gregory Palamas by Gregory Papamichael that was published in Alexandria in 1911, the book by Father Dumitru is, as a contemporary researcher on his life and work writes, ‘the first systematic theological analysis of Palamite thought and theology’. The well-known study by Father John Meyendorff, Introduction à l’étude de Gregoire Palamas, was to appear twenty years later. Unfortunately, due to the political situation and the limited use of Romanian outside Romania, Father Dumitru’s studies have not reached such a wide audience.

This ‘Palamite period’ in Father Dumitru’s career as an academic theologian was to prove of immense importance to his theology. St. Gregory Palamas, with his fully formed system of patristic theological belief, provided the means whereby Father Dumitru was able to enter the inner sanctum of patristic Orthodox theology and experience, and through this he discovered the way to true theology, which springs from a personal relationship, ontological dialogue and union with God, from experiencing God’s presence in the world and in history. In the Palamite distinction between God’s essence and His divine uncreated energies Father Dumitru found a way of bridging the gulf that a theological system alien to Orthodoxy had created between a ‘transcendent’ God and the world, and therefore a way of reconciling academic theology with the Christian lives of ordinary people, with the life of the Church. Commenting later on Karl Barth’s theology, he said, ‘I realised that this was not exactly a Christian conception. It overemphasised the gulf, the distance between God and man. It was the well-known theory of man’s separation from God but I overcame the emphasis on the transcendent nature of God in relation to man and the world. I linked this with the concept that I found in St. Gregory Palamas, that God is in direct contact with us through His uncreated energies.’

‘Jesus Christ or the renewal of man’

A few years later, in 1943, Father Dumitru wrote his first Christological monograph, which was characteristically entitled ‘Jesus Christ or the Renewal of Man’ (‘Iisus Hristos sau restaurarea omului’, Sibiu, 1943, 404 pp.). The title itself shows that we are dealing here not merely with a Christological theology but also a Christian anthropology, which can be none other than a Christocentric anthropology. Many things drove Father Dumitru to write this book. His encounter with the Fathers proved decisive since through them he understood that Christianity means above all Christ. A part was also played by the return to a Christocentric approach both in sermon-writing and in the Church’s pastoral life in general, changes that Metropolitan Nicolae had persistently urged his clergy to make. Then there was the theological stand that the serious challenges of Father Dumitru’s time demanded. The book was written at a time when mankind was embroiled in a world war, a time when an anthropocentric civilisation, paradoxically yet also quite naturally, was pushing mankind to the brink of self-destruction, and in so doing manifested an unspeakable disdain for the unique value of the human person. For the first time in the history of mankind millions of people were being killed with no respect for human identity.

The main square at Braşov, near Father Dumitru Stăniloae’s birthplace

The true image of man is Christ. In His person human nature attains its true stature. In this most important work for the first time in contemporary Orthodox theology Father Dumitru developed the ontological dimension of Christology and soteriology, stressing the organic relationship between the person and Christ’s work of salvation. ‘By becoming a man,’ wrote Father Dumitru, ‘Christ will always remain with us as a unique source of salvation. Salvation means having a relationship, close contact, with Jesus Christ and not individually striving to abide by a certain set of teachings. Salvation is not, to begin with, a form of knowledge or morality. It cannot be attained by knowing or doing something, but through living a relationship with Christ… Therefore, seeking salvation means seeking Jesus Christ, seeking a relationship with Him.’

Christ is the full and perfect expression of human nature for in the person of Christ human nature achieves full union with God.

The Romanian Philokalia

The next question was: how can one realise this union with God? This question led Father Dumitru to a new chapter in his theological work, which was no less important. This was the translation and publication of the Philokalia in Romanian. It was not the first time that Philokalic texts had been translated into Romanian. Father Dumitru himself testified to the existence of numerous manuscripts of earlier Romanian translations, which he studied and used.

Within the space of three years (1946-1948) the first four volumes were issued, which cover the first volume of the Greek edition.

Father Dumitru Stăniloae was not simply a translator of the Philokalia but the creator of the Romanian Philokalia in the sense that he enriched the Greek Philokalia in three basic ways: a) by adding new texts of his own choice to the classic Philokalia collection; b) by producing extensive introductions on each text and author; c) by wroting copious commentaries for the whole translation.

Father Dumitru’s now well-known commentaries on the Philokalia could form an original and monumental work in their own right. These commentaries represent attempts on Father Dumitru’s part both to explain and interpret the Phikokalic texts for modern man and also to continue to analyse and enrich their meanings, on the basis of the contemporary experience of the Church. A regular feature of his commentaries is his emphasis on the inner relationship between teaching and life, showing that teaching is an expression of life and is justified only when it is embodied in practice, while life is guided and its authenticity preserved by the teaching of the Church.

Father Dumitru believed that a translation of the Philokalia was even more necessary at a time when the Orthodox world was being beset by pressing religious trends and experiences that were alien to Orthodox spirituality. On this point, he writes in the first volume of the Philokalia: ‘Recently more and more has been said about living out one’s religion, but this kind of living does not lead towards a final goal; it does not guide the human soul in accordance with a set of laws to greater purification and love, but is regarded as a merit in itself, even if it leads nowhere. According to the Fathers, religious life only has value when it makes constant progress towards a final goal, which is its own perfection. The Fathers have given us a lifelong programme to achieve this progress’.

The Romanian Philokalia was finally completed in 1991, on the production of the twelfth and final volume by the same tireless translator. Of the works that Father Dumitru has added to the standard collection of Philokalic texts, the most important are: the whole of Maximos the Confessor’s work Questions to Thalassios, published in Vol. 3; St. John Klimax’s work The Ladder in Vol. 9; Isaac the Syrian’s Ascetic Discourses in Vol. 10; The Spiritual Letters of Sts. Barsanouphios and John in Vol. 11, and The Twenty-Nine Discourses of St. Isaiah the Solitary in Vol. 12.

The Romanian Philokalia, that monumental work in twelve volumes containing some 6,000 pages, played a great, if not decisive, role in the survival of the Christian Church and faith during the recent atheist Communist phase of Romania’s history. During this period the reproduction of texts in printed form was forbidden and the Philokalia circulated in the form of typed copies and photocopies. It is doubtful whether a developed form of academic theology could have played such a role. ‘Together with many other Romanian scholars, Father Dumitru Stăniloae played a vital part in a saving phase of the history of Romanian spirituality, a phase which began in the post-war period and has continued up to the present day and which I would call a Philokalic renaissance,’ wrote the academic Virgil Cândea. Even Emil Cioran, the well-known Romanian nihilist philosopher, wrote to Father Dumitru on his translation of the Philokalia: ‘The Philokalia is one of the greatest monuments in the history of the Romanian language and Romanian civilisation. At the same time what a lesson in spiritual depth for an unfortunate and superficial nation! In all respects, such a work stands to play a very important role…’.

For the doctrinal thinker Dumitru Stăniloae contact with the Philokalia proved decisive. Father Dumitru discovered, and he stressed this point, that the Philokalia had a profound theological basis and, what is more, a Christological one. ‘The way of life that is described in the Philokalic texts is a fundamentally Christological and Christocentric one,’ wrote Father Dumitru. ‘It is the only one that promotes a relationship and union with Christ and between men themselves. This conclusion is based on the fundamental discovery that what man does is not separate from what Christ does. Whatever man does he does not do alone but with the aid of Christ and the Holy Spirit’.

This synergetic view of man’s life and activities is possible only in Orthodox theology as the Western Christian tradition does not speak of Christ’s uncreated energies, which work in man and strengthen man’s own energies. Thus Father Dumitru shows that Philokalic spirituality is a fruit of the Church’s dogmatic theology, while at the same time it also underpins the theology of the Church.

The Christological basis and structure of the Philokalia convinced Father Dumitru that he should give a Philokalic basis to his dogmatic theology, a feature that perhaps represents his most important contribution to contemporary Orthodox theology.