The What Where, When, and Why of Orthodox Missions

11 May 2017Is missionary work an Orthodox practice? Should our Faith be earned to all peoples of the globe? Can all Orthodox Christians participate in mission work? The answer to each of these questions is a resounding, “Yes!” In this article we will explore the history, methods, and motivation behind Orthodox missions, arriving at the conclusion that not only can we participate in missionary work, but as children of God, the spreading of His love is a part of our very nature!

Is “Orthodox Missions” an Oxymoron?

Early on in my experience as a missionary to Albania, I had an encounter with a Protestant missionary which was soon to become commonplace. We had been having a pleasant conversation when the topic turned to our respective ministries. When I told him that I was an Orthodox missionary, his expression turned to one of utter astonishment. All he could manage to blurt out was, “I didn’t know the Orthodox Church did missionary work!”

Actually, I was not offended by his candor. I soon discovered that many missionaries assigned top Albania had little if any knowledge of Orthodoxy. A much more distressing reaction came from Orthodox Christians themselves.

I first encountered this reaction while a student at seminary in preparation for the priesthood. As a member of the campus missions committee, I often spoke about mission work. On more than one occasion in this capacity, I was confronted by a man or woman emphatically telling me that mission activity was unorthodox. “Foreign missions,” I was told, “is a Protestant concept!”

To be fair, it is easy to see where both these misconceptions originated. While Orthodoxy has made a powerful missionary effort through much of its history, it was as recently as 1962 that Orthodox scholar Nikita Struve observed pointedly: “Strictly speaking, the Orthodox Church has no longer any organized mission.” ‘

A Temporary Period off Decline

Without question, the Orthodox Church has been active in missions from its very beginning—from the Apostolic and Early Church period, through the Byzantine and Russian eras, and now in the present day. Any reading of the history books will clearly substantiate the fact that each century has brought forth vibrant Orthodox mission activity.

Two factors, however, greatly thwarted the Church’s missionary efforts in recent centuries: (1) the Turkish occupation of the Balkans, lasting four centuries; and (2) the communist seizure of power in many other Orthodox countries. Between these two events, the ability of the Orthodox Church to do missionary work was repressed at a time when the churches of the West were free to expand. These events “forced the Orthodox to withdraw temporarily into themselves in order to preserve their faith and to form, to a certain extent, closed groups.”2

Praise be to God, that period came to an end around the middle of the twentieth century. Following the 1958 Fourth General Assembly of Syndesmos in Thessaloniki,Greece, the newly arising Porefthentos movement brought forth an Orthodox revival in the area of external mission. If one sorts through the various documents written after that period, the growth of this revival becomes clear. The call to the Church to return to its task has appeared over and over again in conferences and articles during the last forty years.

In addition, the severe communist rule that repressed Orthodoxy in so many other countries of the world has now collapsed, and we can expect to see this same reawakening of missions in these countries as well.

A Survey off Mission Activity

In looking back, one can see that this call to return to missions has borne fruit. The Orthodox, after decades of repression, once more have begun witnessing to Christ to the “ends of the earth.” The number of Orthodox missionaries, in comparison to those of other churches, is not spectacular. Yet a survey of current Orthodox mission activity reveals that the Church is on the move once again. Let me outline some of the main regions of Orthodox mission work that I have explored.

• The Ecumenical Patriarchate of Constantinople covers a number of missionary regions. The largest is the Metropolitanate of Hong Kong and Southeast Asia, established in November, 1996. Metropolitan Nikitas, from Tarpon Springs,Florida, was enthroned to this See in 1997. The jurisdiction covers a large territory, and mission efforts include Indonesia, India, the Philippines, Hong Kong,Korea, and Singapore. The Metropolitan writes that there are also possibilities waiting to begin inChina (Beijing),Taiwan, and Thailand (Bangkok).3

• The Orthodox communities of Central and South America also carry on local missionary activities. Efforts in these areas are led by Constantinople and by other jurisdictions as well.

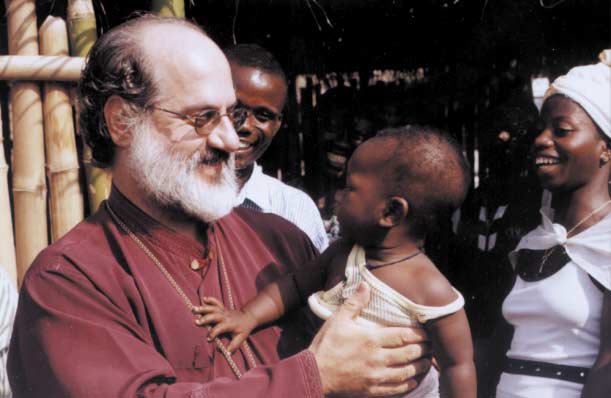

• The Patriarchate of Alexandria and All Africa is responsible for the mission efforts in Africa. The Orthodox churches of Africa are growing daily. The main missionary efforts are in Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, Madagascar, Zaire, Cameroon, Ghana, and Nigeria. In all of these churches there are indigenous clergy. Some have seminaries, and many have schools and clinics as well.

• The Autocephalous Church of Albania. A new situation in Orthodox missions arose in this decade. With the collapse of the communist regimes in countries that had previously been predominantly Orthodox , the Church often found itself with the task of rebuilding its foundations from the ground up. This is especially true in the Church of Albania, where religion was constitutionally illegal and the infrastructure of the Church had been totally destroyed. In this situation, the only way the Church could be resurrected was through outside assistance, reaching across cultural and geographical boundaries.

At the head of the effort in Albania is Archbishop Anastasios Yannoulatos, the Orthodox Church’s foremost living missionary and missiologist. Archbishop Anastasios was elected to lead this Church and has done an outstanding job in applying the best of Orthodox mission strategy over the past eight years. It is one of the few countries where Orthodox can freely witness to a Muslim majority, and many are turning to the Faith.

• Mission Centers: Another development in Orthodox mission work of the past decades has been the revival of the idea of mission centers to support external mission. We have seen the first of these (Porefthentos) in Greece, beginning in the 1960s. Since this time other movements also have begun in Greece. The Orthodox Christian Mission Center represents all the canonical Orthodox jurisdictions in the United States. A third movement came into existence in Finland in 1981 (Mission Office of the Finnish Orthodox Church, Ortodoksinen Lahertysry). The Moscow Patriarchate has also recently revived its Office of Missions.

If we look back through the history of Orthodoxy until today, we can see that the Orthodox Church has been involved in mission work from its very beginning. Though there was a time of inactivity due to external political persecution, when freedom was restored the Orthodox Church again applied itself to the Great Commission to go to all nations.

The Principles of Orthodox Mission Work

What are the principles of Orthodox mission work? Can a common thread be found in the many efforts throughout the centuries? If so, how does this compare to contemporary Protestant mission strategies?

While attending Fuller School of World Missions, I was given a wonderful opportunity to sift through different Protestant strategies of missions. These strategies are in a constant state of development. As I applied them to my own context, I soon realized that the best of many of these theories in modern missiology could be found already existing in my own Orthodox tradition. Additionally I realized that some of the great mistakes of missionary history were absent in the Orthodox approach. Let me illustrate what I mean by briefly outlining just a few of the more popular contemporary mission theories, and then contrasting them to the Orthodox approach.

• The Three-Self Church. The first theory is called the “Three-Self Strategy ” It represents the realization that missionary work should ultimately lead to the development of an indigenous church. According to this theory, an indigenous church is described as one that is self-governing, self-supporting, and self-propagating. Henry Venn and Rufas Anderson developed this emphasis to correct the negative results of nineteenth century mission work, which had resulted in paternalism by the missionaries and the establishment of churches that were totally dependent on the foreign missionary bodies. As one missionary put it, a scaffolding was being built around the churches, but it remained as a permanent fixture, rather than being a temporary aid towards creating a self-standing structure. In the Three- Self model , an emphasis was placed on the indigenization of the local church: it must incorporate and fully function within the local, indigenous culture to be authentic.

• Contextualization. As the Three-Self model was applied, however, certain weaknesses surfaced. It was found to be too simplistic to consider a church mature when it contained the three “selves” and functioned within the local culture. The contextualization model accepts the Three-Self presuppositions, but also points out that in certain situations a church could be indigenous without one of these aspects. It also reveals that a church could contain the Three-Self dimensions but still be a totally foreign entity in its culture, even though it is run by the indigenous people.

Thus the contextualization model looks to deeper issues to determine that a church is firmly rooted in the culture and life of a people and has become contextualized, in addition to being indigenous.

• Translation of the Bible and use of local language. Another related emphasis of Protestant mission strategy involves the issues of Bible translation and the use of the local languages. A people must be able to read and worship in the “language of their heart.” The Bible must be made available to form a mature church. These are commonly accepted principles today that are found across the spectrum of almost all Protestant missionary efforts.

An Orthodox Perspective

It is interesting to note that most of these models were formulated in response to weaknesses in historical Protestant missionary efforts. Too many missionary efforts denied or repressed the culture of the people being reached. Others neglected to translate the Bible, or use the local language or music in worship. How then does the Orthodox Church relate to these principles in its missionary work, and what has its practice been throughout the ages?

In an article published in 1989, Archbishop Anastasios outlines the key emphasis in the Byzantine and Russian Orthodox missions. The Byzantine missions, he states, were based on clear-cut essential principles:

At the forefront was a desire to create an authentic local eucharistic community. Thus precedence was given to translating the Holy Scriptures, [and] liturgical texts … as well as to the building of beautiful churches which would proclaim—with the eloquent silence of beauty—that God had come to live amongst humanity— [There was also an] interest in the social and cultural dimensions of life At the same time, the development of the vernacular and of a national temperament . . . helped preserve the personality of the converted peoples. Far from indulging in an administrative centralization . . . the Byzantine missionaries saw the unity of the extended church in its joint thanksgiving, with many voices but in one spirit.4

He goes on to outline the Russian missions:

The Russian missionaries were inspired by the principles of Byzantine Orthodoxy and developed them with originality . . . the creation of an alphabet for unwritten languages; the translation of biblical and liturgical texts into new tongues, the celebration of the liturgy in local dialects, . . . the preparation of a native clergy as quickly as possible; the joint participation of clergy and laity, with an emphasis on the mobilization of the faithful; care for the educational, agricultural, and artistic or technical development of the tribes and peoples drawn to Orthodoxy.

In summing up the many principles of Orthodox mission strategy, Archbishop Anastasios states, “Certain fundamental principles, only now being put into use by western missions, were always the undoubted base of the Orthodox missionary efforts.” 6

This is a key point in understanding historical missionary activity. Many of the current missiological principles just now being discovered by Protestant missionary studies can actually be found in practice throughout centuries of Orthodox missions!

Even more encouraging, however, is the fact that the strategies adopted by historical Orthodox figures—from Ss. Cyril and Methodios to St. Nicholas of Japan and St. Innocent of Alaska—are also practiced in the present day.

Having served under Archbishop Anastasios for the past ten years, I have personally witnessed the same spirit, direction, and integrity in the mission work he has led in East Africa and now inAlbania. Each of these traditional Orthodox emphases has been present: translation, worship in the local language of the people, indigenous leadership, participation of laity, incorporation of cultural elements into the life of the Church, building of churches that witness to the glory of God, and an emphasis on the whole person by addressing the needs of society both through education and charitable institutions.

These are the threads of Orthodox mission practice that are woven throughout its history. These are the ideals that the Orthodox strive for when carrying the gospel to new lands and peoples. While they have not always been present in each and every movement, they are an undeniable part of Orthodox history stretching from the first centuries until today.

Why Should We Do Mission Work?

I would like to address one final question before concluding this article: Why should we do mission work?

I will never forget my first flight to Africa. Newly married and ordained, I had become a missionary overnight. One moment I was a priest in California. It only took a split second, though, for my foot to step through the threshold of the 747 that was to carry us to Kenya. With that magic step our family became missionaries.

Now, as we were flying over the Atlantic, a flight attendant saw my collar and asked where I was going. I proudly explained that our family was traveling to East Africa to be missionaries. “Oh,” she replied. “I don’t believe in that. We should not interfere in people’s lives. We should just leave them alone to continue on their own happy way.”

How do you answer a statement like that? Where do you begin? In fact, this challenge is one that came up time and again and gradually forced me to think, analyze, and study the very bedrock motivations for doing missionary work. Why don’t we just leave the world alone? Why do we try to spread our Faith to people who have their own beliefs?

Somewhere along my journey toward the missionary vocation, I came across an Orthodox perspective presented by Archbishop Anastasios in a paper called, The Purpose and Motive of Mission. This paper became a watershed for me, since it seemed to encompass everything I had been learning and experiencing as a student and missionary. With this in mind. I can think of no better way to conclude this article than with a brief summation of the excellent points made by Archbishop Anastasios in his paper.

Without question, the foundation for mission is the glory of God and the redemption of all creation. The Scriptures emphasize this theme over and over again, beginning with Creation itself, and leading us through the rejection of that glory and the subsequent entrance of death into the world. Jesus’ life, from this perspective, is a manifestation of the glory of God. In Christ, human nature is redeemed and the universal order restored. Finally, the Church becomes a participant in proclaiming this redemption until the Parousia, when the glory of God is fully revealed.

Participation in spreading the glory of God is so basic to the Christian spirit that it may be called an inner necessity. Archbishop Anastasios explains:

The question of the motive of mission can be studied from sev- eral angles: love of God and men, obedience to the Great Command of the Lord (Matthew 28:19), desire for the salvation of souls, longing for God’s glory. All these surely, are serious motives. . . . However, we think that the real motive of mission, for both the individual and the Church, is something deeper. It is not simply obedience, duty or altruism. It is an inner necessity. “Necessity is laid upon me,” said St. Paul, “Woe to me if I do not preach the gospel” (1 Corinthians 9:16). All other motives are aspects of this need, derivative motives. Mission is an inner necessity (i) for the faithful and (ii) for the Church. If they refuse it, they do not merely omit a duty, they deny themselves.7

This inner necessity is an outgrowth of our being made in God’s image. Throughout history, we can clearly see God’s purpose in the revelation of His glory, the drawing of all things to Himself, and the establishment of His Kingdom. In addition, we can see that God has shared this mission with humanity, from Abraham to Jesus’ disciples and on to the Church today.

Thus mission work is not a task which is simply imposed upon us; nor is it rooted solely in our obedience, respect, or even love of God. Rather it is the actualization of our inherent nature to participate in the fulfillment, destiny, and direction of humanity and all creation as it is drawn back to God and towards the coming of His Kingdom.

Conclusion

In this article, we have considered the longstanding and sometimes forgotten tradition of Orthodox missionary work. Space has not allowed us to explore in depth the loving characters, the powerful visions, the solid strategies, and the intensely sacrificial lives of so many Orthodox missionaries.

But in this broad overview of Orthodox mission history, strategy, and motives, I have attempted to give a taste—if ever so faint—of the rich flavor of a vibrant history that continues in the present and which is at the very heart of our being. As Orthodox, we have been, and must be, involved in missionary work. We have a firm historical tradition and developed principles which tell us this.

Most importantly, we have an understanding that bringing God’s love, compassion, and message to the world, drawing people to Him and establishing worshipping communities among all nations and in all cultures is not merely an imposed command or a religious principle—it is a part of our own nature as we are created in the image and likeness of God.

Participation in missions, both as individuals and as a Church, is an action necessary to our fully being who we are. Without it something will be lacking. With two-thirds of our world still missing the love and joy of being in Jesus Christ, we have much to do. May the Lord guide us to actualize this dimension of ourselves so that His saving power may be known among all nations.

1 Nikita Struve, “Orthodox Missions: Past and Present,” St. Vladimir’s Theological Quarterly 6:1, pp. 40, 41.

2 Yannoulatos, Anastasios, “Orthodoxy and Mission,” St. Vladimir’s Theological Quarterly 8:3. p. 139.

3 The Censer, Jan. 99, Vol. 3, Issue 1.

4 Yannoulatos, Anastasios, “Orthodox Mission—Past, Present, and Future,” Your Will Be

Done, Orthodoxy in Mission, George Lempoulos ed.,Geneva: WCC. 1989, pp. 65,66.

5 Ibid., p. 68

6 Ibid., p. 68

7 Yannoulatos, Anastasios, The Purpose and Motive of Mission: from an Orthodox Theological Point of View. Athens: Typo-Tcchniki-Offset, Ltd.. 1968, (3rd edition) p. 32.

By Fr. Martin Ritsi This article originally appeared in Conciliar Media Ministries’ Again Magazine, Vol. 22.1, and is posted here with permission. Be sure to visit Conciliar Media at either Conciliar Press or Ancient Faith Radio.