Energy and personality in the theology of John Meyendorf and in contemporary philosophy

15 October 2018Contemporary man… should be more receptive to the basic positions of Byzantine thought, which may then acquire an astonishingly contemporary relevance.

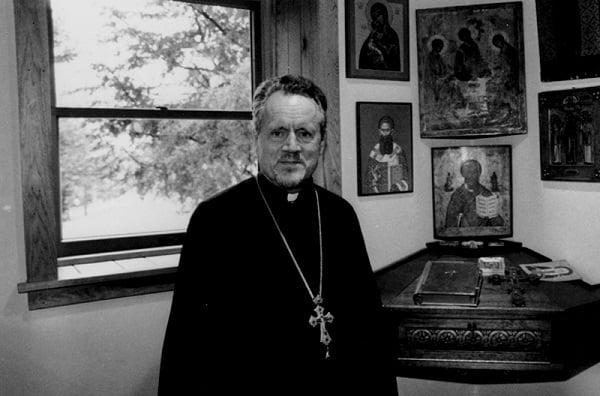

Fr. John Meyendorff

Many ideas and positions propounded and maintained in the works of Father John Meyendorff are taken now by us as evident and well-known, as commonplaces. We must, however, make an effort to see them in the right way: before Meyendorff, they did not belong to commonplaces, and they have become universally recognized due to him. In cultural process the fate of commonplaces is unenviable. Although they are exploited permanently, they are never appreciated and are treated with no respect; and when one looks for something new and original, one chooses often the easy way of denying and rejecting of commonplaces (or things that seem to be only commonplaces).

Such cases can be found nowadays in Orthodox theology too, including the reception of Meyendorff’s work. Most often, looking for a new vision of the theological process, one uses standard paradigms of cultural and intellectual development, in which the basic mechanism of development is identified with the generation of new phenomena and trends that are characterized as “neo-” or “post-“forms of the old trends. In this line, voices are heard today, which qualify the work of Lossky, Florovsky, Meyendorff as obsolete, and claim the necessity to overcome this stage, to go to “post-patristics” and so on. Such tendencies give rise to doubts, however: they do not take into account the specific nature of spiritual tradition, which is different from the nature of cultural or scientific traditions. Spiritual tradition is rooted in spiritual practice and long since conceived in Orthodoxy as the “Living Tradition”; and it has its own paradigms of growth and creative continuation, which are different from producing “neo-“ or “post-“ formations. Christian martyrs were not “post-apostles” and st. Gregory Palamas was not a “neo-Cappadocian”! Cultural and scientific paradigms describe a discrete series of successive modernizations or revolutions, while for spiritual tradition the aim and norm of its existence is the continuity of the transmission of the authentic Christian experience, which always remains the same, identical to itself as the experience of communion with Christ, although it may take various changing forms and empiric existence of the tradition may have interruptions and periods of decline. Thus Meyendorff wrote as follows: “In no way facts of our contemporary situation mean that we need what is called usually “new theology” that breaks off with the Tradition and continuous succession”[1].

Thus the custody and identical transmission of the originative generating experience of Christianity is the unchangeable main task of Orthodox consciousness and Orthodox spiritual tradition. It is in the light of this task that we should appraise the current situation of the Orthodox thought and determine its strategies. The universalized interpretation of Greek patristics presented by Florovsky (the core of which is nothing but the ancient idea of the Living Tradition) tells us that Orthodox patristics should be conceived as a phenomenon that is not restricted to the limits of a certain period, but represents a definite type of consciousness and mode of thought: namely, the consciousness that accepts the above-mentioned task and gives it the central place. Clearly, for this interpretation even neo-patristics is a rather questionable and not quite adequate term, while post-patristics is simply synonymous to post-Orthodoxy. And similarly the work of Meyendorff in its basic ideas and results, as I shall try to show, not so much belongs to some or other transitory and changing theological or philosophical trends as reveals anew some important aspects of the unchanging foundations of Orthodoxy for modern consciousness and in its language.

Here I shall discuss this work in its philosophical aspects only. For Fr. John these aspects were not the principal ones, but in this field his works have also opened new perspectives, which were then developed in contemporary philosophy. The subject matter of these works is connected, in the first place, with the study of Byzantine theology and st. Gregory Palamas’ thought. One can say without any exaggeration that Meyendorff has presented a new reception of this thought, thorough and well-founded. From the philosophical viewpoint, the essence and principal significance of this reception can be seen as follows: together with the preceding works of Fr. Basil (Krivoshein) and Vladimir Lossky, it paved the way for the renaissance and new development of what is called often Orthodox energetism. It is preferable to understand this popular formula not in the narrow sense of some concrete theological or philosophical teaching, but in the large sense of a certain type of mentality, which makes the cornerstone of the living experience of the connection with God and perceives reality as the arena of action of God’s grace and man’s response to the grace. It is the ancient Orthodox-ascetic way of the vision and perception of reality, but there were long historical periods when it was overshadowed and pushed aside, and did not find any explicit and articulated expression. In the middle of the last century Orthodox consciousness has successfully overcome one of such periods, long and difficult, and Fr. John Meyendorff has contributed greatly to this success.

Now, it must be said that what Meyendorff points out as the main general characteristics of Orthodox mentality and theology is usually not energetism, but personalism (“Christian personalism, “theological personalism” etc.). It is also conceived not as some concrete doctrine or theory, but in the large sense of a certain general approach to problems of the conceptualization of the God – man relation and all the divine-human economy. The distinction of this approach is that the first and immediate subject of discussion in the teaching on God is Divine Hypostases, Father, Son and Holy Spirit, from which one proceeds then to the consideration of Divine Essence. (One adds usually that in the Western theology, whose approach is called “essentialist” by Meyendorff, the consideration proceeds in the inverse order.) For our theme two features of this personalist perspective as it is presented by Meyendorff are particularly important.

[1] John Meyendorff. Orthodox theology in modern world // Id. Orthodoxy in modern world. N.-Y., 1981. P.167. (In Russian.)

The first feature concerns the relation of this perspective to philosophy. It is well-known that the conceptions of the hypostasis and the personality conceived as the hypostasis are absent in ancient metaphysics and are alien to its discourse: they have been created by the Cappadocian Fathers and have become the origin and foundation of a cardinally different discourse, that of Christian dogmatic theology. Because of this, the popular thesis repeated often, among others, by Fr. Georges Florovsky: “The idea of personality was the greatest contribution of Christianity to philosophy”[2], – should be made more precise. Meyendorff points out justly that the Orthodox personalism, the primacy of the idea of personality in Orthodox thought, was the factor, which made this thought not closer to, but more distant from philosophy and also, to some extent, from Western theology. Classical metaphysics, both in antiquity and modernity, was in no way metaphysics of personality. Its notions of the subject and the individual are deeply different from the Orthodox theological notion of the personality-hypostasis and all its discourse called also essentialist by Meyendorff is inadequate for rendering the personalist character of Orthodox experience[3]. Thus Orthodox spirituality in all its history found some philosophical expression only rarely and partially.

A more systematic attempt for such expression is found in the thought of the Religious-philosophical renaissance in Russia in the beginning of the 20th c.; but, in the whole, this thought still belonged to classical metaphysics and, as a result, the attempt had rather limited success (although many prominent and bright thinkers took part in it). Fr. John was reserved and a bit skeptical about this thought and in some of his texts he criticized one of its main trends, sophiology. In the light of this long negative prehistory, it is not unimportant that in the last decades of the 20th c. some preconditions have arisen for positive changes in the relations of Orthodox thought to both philosophy and Western theology. In theology, Meyendorff himself noticed it when he wrote: “There is a return to an existential and experiential approach to the doctrine of God”[4]. As for philosophy, it has “overcome” classical metaphysics and this overcoming has considerably changed its positions in the problem of personality. After the big epistemological event of the “death of the subject” European thought has entered the phase of the intense search, the main theme of which is expressed by the title of the important collection of essays published by a large group of influential Western thinkers (Derrida, Deleuze, Nancy, Marion e.a.): “Who comes after the Subject?” (1991). The search develops over all the vast conceptual space from the Cartesian subject of knowledge to the Christian man forming up his identity in the openness to God and communion with Him, and below we shall discuss its results and prospects.

The second feature of the personalist perspective is its closest connection with the conception of Divine energies. According to Meyendorff, it is only in the “energetism” of the Orthodox teaching on God and man that the “personalism” of this teaching is implemented concretely. The divine personal (hypostatic) being, both ad intra, in its Trinitarian life, and ad extra, in its actions in the world, is realized by means of divine energies. In their turn, these energies as they are described in Orthodox theology are closely connected with the economy of the Hypostases so that all the conception of divine energies can be formulated only in the framework of the “personalist” vision of divine reality. Thus Meyendorff writes: “Le personnalisme théologique est le trait fondamental de la tradition à laquelle se réfère Palamas: nous y trouvons la clef pour comprendre sa doctrine des énergies divines”[5]. Orthodox teaching, as he sees it, is characterized by the permanent intertwining of these two basic principles and approaches. The personalism of Orthodox thinking is combined everywhere with the energetism: the first principle describes the general character of things and processes, while the second one discloses, as far as it is possible, the inner life, dynamical relations and mechanisms of these things and processes.

On the theological side, such permanent intertwining of personalism and energetism has generated a big circle of problems concerning the vast and complicated theme of interrelations between the Hypostases of the Holy Trinity and divine energies. Many of these problems were not discussed in Palamas’ works; Meyendorff draws attention repeatedly to “le caractère manifestement inachevé de la pensée du docteur hésychaste” and the commentator of the Russian translation of his “Introduction” (V.M.Lurie) adds here that “the impression of the incompleteness of the teaching of st. Gregory Palamas was created mainly by the absence of clarity in the relationship of the energy of God to His Hypostases”[6]. But our theme prompts us to consider this intertwining from another side, philosophical. Leaving aside theological controversies, we notice first of all that from the purely philosophical viewpoint, the union of personalism and energetism is an original configuration of principles unusual for philosophical tradition. Energy and Personality are two fundamental subjects of philosophizing, which both have their long history and their discourse in European philosophy, but these histories and discourses were almost completely separate from each other. There is one important common moment between them, but of negative character: both Energy and Personality found extremely little attention and understanding in classical European metaphysics. If we define, following Heidegger, the principal feature of this metaphysics as the “forgetting of being”, one can continue that the main components in this forgetting were exactly the forgetting of energy and the forgetting of personality. In both cases the forgetting took the form of the substitute. As Heidegger argued in great detail, the substitute of energy in the Western thought was the “act” (because the Greek energeia was translated in Latin as actus), and the meaning of the two terms is so radically different that the substitute caused the catastrophic loss of all the profound originality of the ancient Greek thinking. The “subject” (the Cartesian subject of knowledge with all its correlates and derivatives) can be considered as a similar substitute for personality, and one can say perhaps that mutatis mutandis the consequences of this substitute were also similar as they led to the loss of the profound originality of Christian vision.

Nowadays classical metaphysics has already gone, however. The “overcoming of metaphysics” is essentially completed and European philosophy proceeds in post-classical space, trying to find there its new principles and paradigms. In the époque of post-classical thinking history of energy and history of personality both enter a new stage. Both fundamental principles did not belong to the old classical foundations of philosophical discourse and now they are seen as underestimated and misunderstood formerly and hence demanding a new interpretation. They attract increasing attention, and who knows? perhaps they might become basic principles of post-classical philosophy.

In this situation, the Orthodox teaching as presented by Meyendorff opens one of possible ways to a new modern treatment of both energy and personality. The main distinction of this way is the closest inner connection of the two principles, which was in no way inherent in their former philosophical treatment. Of course, there are no prepared philosophical notions and conceptions here, but a certain kind of experience is opened here to philosophical mind, the experience, for which energy and personality are the key generating and organizing principles. Reflection of this experiential base can provide ideas and reference points for philosophical interpretation of these principles. Now we are going to discuss briefly the arising interpretation of energy and personality in comparison with the treatment of these principles in contemporary philosophy.