The Theology of Touch: Symbols in the Works of Van Gogh and God’s Revelation

28 January 2019‘A week later his disciples were in the house again, and Thomas was with them. Though the doors were locked, Jesus came and stood among them and said, “Peace be with you!” Then he said to Thomas, “Put your finger here; see my hands. Reach out your hand and put it into my side. Stop doubting and believe”. Thomas said to him, “My Lord and my God!” Then Jesus told him, “Because you have seen me, you have believed; blessed are those who have not seen and yet have believed”’ [1].

This passage from the New Testament is very well known to Christians everywhere, referring, as it does to Doubting Thomas, Christ’s disciple. He believed in Christ, but, in order to be convinced of His resurrection, wanted tangible proof, so that he could confirm the wounds in the body of the risen Lord through his own sense of touch. Christ also used this same sense of touch in performing His miracles, even though His word alone would have been enough to work them. He did so to highlight, apart from words and sight, ‘the life-giving and enlightening power of His body, His own body, sanctified with the hypostatic union of the body of Life and Light’ [2]. We can therefore talk about revelation of the Divine Word which is not restricted to senses of sight and words [hearing and speaking], but extends also to the sense of touch. In His miracles, Christ used the sense of touch: He touched the eyes of the blind and they regained their sight; He touched the dead and they arose. Another example of miraculous proof through touch is the Divine Eucharist, the partaking of the Body and Blood of Christ, which is celebrated in remembrance of Christ, His Passion and His resurrection, and which heralds eternal life.

Rembrandt,“The Raising of Lazarus”, 1632, Etching and engraving, New York. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

The Dutch post-Impressionist artist Vincent Willem van Gogh (1853-1890) attempted to become a preacher. He tried to gain entry into three theological institutions before turning to art when he was 28. The rejection of the painter by the theological institutions hurt him greatly and frustrated him to such an extent that he turned away from religious systems and began seeking a different approach to the divine. This was the way of aesthetics, and, in particular, the path of painting. In Orthodox theology, aesthetics is part of Dogmatics, regarded as a bridge conducting people towards the divine, as a unifying reality we experience when we attempt to describe the divine through our senses. There is, however, no definition of aesthetics, strictly speaking.

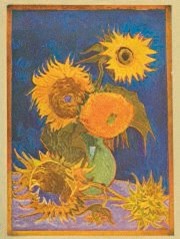

Through his 902 letters, mostly addressed to his brother Theo (Theodore), he kept him informed on the latest news regarding his works, his concerns, his dreams and his relationship with God, a relationship which comes across in almost all his letters as being fluid and active. Van Gogh also refers in his letters to the symbols he uses in his works. He often uses the sun to express the presence of God, for example. Typical of this is his reprise of Rembrandt’s engraving The Raising of Lazarus (1632), which he executed while he was at Saint-Rémy, in 1890. The figure of Christ in Rembrandt’s work is absent in that of van Gogh and in His place is a bright yellow sun. Another symbol of the sun are sunflowers and their various reproductions. The words used by van Gogh to describe his sunflowers are religious. It was with sunflowers that the artist wanted to decorate his new studio in his house in Arles, where he lived with his friend, the primitivist artist Gaugin. He imagined their colours and described them to his friend, the artist and author Bernard. In some way, they were ‘Sorts of effects of stained-glass windows of a Gothic church’ (Arles, LT665). Elsewhere, he talks of ‘halos’ on a royal blue background, ‘that’s to say, each object is surrounded by a line of the colour complementary to the background against which it stands out’ (Arles, LT668). In this letter, he also calls these particular flowers ‘suns’.

Vincent van Gogh, “The Raising of Lazarus (after Rmbrandt), 1890, Washington, National Gallery of Art.

Sunflowers, 1889, Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam.

The colours van Gogh chose to use in his works were intense and had their own function. What was impressive in the mostly self-taught Dutch artist was the thick layers of colour he employed. According to him, he did so because in this way the colours were more durable and also more vivid. From a modern point of view and with progress in technology, in conjunction with the demands we have today, this perspective on works of art, with viscous layers of colour, provides an answer to approaching art through touch. It is now common practice in large modern museums to use 3D prints of great works of art so that people whose sight is impaired can touch the works and understand what they represent. Van Gogh may not have had any such intention or prospect for his works, but this technique can certainly be applied in order to reproduce the paintings. People with limited sight have the chance to touch the work, understand the subject matter and- even more important- have the opportunity to move on to another level of understanding the painting, that of the symbolism.

Still Life: Vase with Five Sunflowers, 1888. Destroyed by fire in World War II.

Saint Thomas the Apostle felt Christ’s wounds in order to reach Him; visitors with impaired sight can, in the Van Gogh Museum, for example, reach out and touch most of the artist’s paintings of sunflowers, which are housed there. We, too, in a similar manner, can reach out and seek Christ through the sense of touch [3]. This modern method might not have been something van Gogh consciously sought, but he was one of the first to make it available to us through his art. Indeed, it was one of the artistic aims of van Gogh that his works should bring consolation. What he himself sought through his art was light and, by extension, God, beyond the patterns and limitations he attempted to express, describing in a unique artistic manner the experience of his relationship with Him and also describing the world of created things.