The Unity which Saves (Eph. 4, 1-7)

11 December 2019In his Epistle to the Hebrews, Saint Paul says that the word of God is sharper than any double-edged sword (4, 12). Today we don’t use double-edged swords so much. Most often we come across them in museum collections or as ornaments in drawing-rooms. Woe betide us if we’ve made the ‘sword of the Spirit’ into a household ornament. A modern theologian justifiably asks, ‘What’s the point of a theology which isn’t action?. And what’s the point of a theology which is brandished as a weapon against unbelievers and isn’t ptroductive in those who profess it?’

The fruits of humility

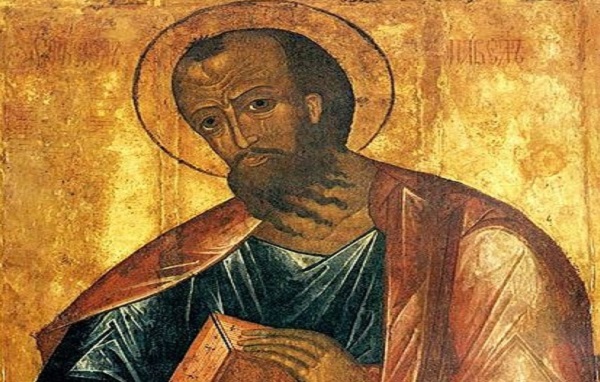

This danger is what Saint Paul wishes to prevent in the second part of his Epistle to the Ephesians, which is the reading for today [the 10th Sunday of Luke]. In the first part, he set out his teaching on the redemptive work of Christ, which embraces Jews and Gentiles alike, without distinction. Here he describes the practical consequences of this teaching. For Saint Paul, dogma and life are two sides of the same reality. This is why it’s very natural to recall, again, that he’s a prisoner in the Lord. Theodoritos says ‘The memory of the chains is enough to incite to the cultivation of the virtues even the most unfeeling. It’s astonishing that Saint Paul is prouder of his chains than a king is of his diadems’. And how can Paul not be proud when, along with Saint John Chrysostom, he recalls that ‘Our Lord, Who freed the whole word of its chains, was Himself bound’. Therefore ‘Let us also rejoice that, even if we’re not in perceptible chains, we’re bound in obedience to His commandments’. It is only in such bondage that we can follow the way of life of our high calling. Saint Theofylaktos asks if there is any calling more sublime that ‘to sit with Christ on His throne and to reign with Him?’

But unlike royal enthronements, this call to honor first requires practice in humility. Humility, which Chrysostom calls ‘a necessary condition for all the virtues’, is the first thing required by Saint Paul. When the words ‘ humble’ and ‘humility’ were transplanted from the ancient Greek world into the Christian one, they changed their meaning in a way that clearly demonstrates how Christianity transformed human society. In ancient Greek literature, the word ‘humble’ usually means ‘socially insignificant’ and was applied mostly to slaves. It first acquired a positive meaning in the New Testament, where Christ is projected as a model of humility (Phil. 2, 6). Since then, humility has been considered a fundamental feature of the ‘new’ person. The other virtues cited by Saint Paul- meekness, long-suffering, forbearance and love- can’t flourish without humility.

The ‘fire’ that unifies

The image of flowers, of course, conjures up the danger of comparison- which one is the most beautiful and fragrant- and this cancels out the sought-after ‘band of peace’. This may be why, instead of the image of a bunch of fresh flowers, Saint John Chrysostom prefers that of a bundle of dry sticks as a simile for the virtues, making them humble and free of the ‘sap’ and swelling of prideful souls. Because they’re dry, it’s easier for them to unite in the fire of the Holy Spirit: ‘the fire makes all of them one; when they’re wet, however, they neither burn nor do they come together’.

‘Ablaze’ with this fire, Saint Paul launches into a wonderful hymn on the unity of Christians, which celebrates communality: ‘One body, one Spirit, one hope, one Lord, one faith, one baptism, one God’. He would declare the same powerful message- with much pain- to the Corinthians who were threatened by factionalism: ‘All of us have been baptized in one Spirit and into one body’. Chrysostom shares this pain when he asks: ‘How is it possible for you to have divergent views when you’ve received the same Spirit, have been watered from the same spring and are supported in the same hope? God doesn’t us simply to be united among ourselves, nor simply to live in peace and love with one another; He requires that we be one soul and one body’.

United and separated

This wonderful unity among Christians is no human achievement; it’s the work of the Holy Trinity. Starting with Athanasios the Great, the holy Fathers have interpreted Paul’s words ‘one God, one Father of all, over all, through all and in all’, in the following way: ‘Over all as Father, as beginning and source, through all, through the Word, in all, in the Holy Spirit’. From these words it’s clear that within the Church we experience the mystery of unity in two dimensions: on the one hand with other people, but also with God. In neither of these unions, however, do we lose our personal integrity, our awareness of self or our freedom. In our union with other people we don’t become mindless pieces of an amorphous and faceless mass; nor are we lost in our union with God, as if we were drops in the ocean.

The most convincing proof that unity in the body of the Church is the best ‘greenhouse’ for the growth and development of the separate beauty of each human person is the last verse of today’s Epistle reading, where Saint Paul refers to the various gifts given to us by God as we’re suited to them and in our best interest and for the good of the Church.