Theological and Scientific Theories of Knowledge (2)

15 January 2020[Previous post: http://bit.ly/2tVErcJ]

This personal nature of the truth is of prime significance for us. The living truth cannot be objectified, because its objectification would be tantamount to its ossification and necrosis. Knowledge of this truth is an experience of life: it is the fruit of the union of two subjects into one and the same Being, God and the human person. Neither of them becomes an ‘object’ and both, God and the person, live this event as a unified life [8]. This realization is of particular importance in terms of approaching and evaluating any specific truth we might be seeking in our life.

As a means of addressing secular truth, scientific research has a positive value. The same is true for the accomplishments and applications of this research. All of this is not the work of the devil, but of human beings who were created ‘in the image’ of God. Of course, given this creation ‘in the image of God’, it is incumbent upon us to keep our vertical relationship with Him alive. Our nous, which is the highest element of our existence, should be illumined by God. In any case, it is only under these conditions that the human nous can function in a natural way. When this happens, the work we produce on the horizontal plane is positive.

As Saint Maximos the Confessor points out ‘the nous works in accordance with nature when it has subdued the passions and sees the causes of beings and lives close to God’ [9]. But even when we function independently of God, following our own will, our accomplishments and achievements are still connected in some way with what is good. Looked at from the perspective of Christian theology, good is all that exists ontologically. Evil is not a position, but a negative value. It is the denial of good, or a ‘parasite on the body of good’ [10]. And as denial of or a parasite on good, which is the only thing that really exists, evil is firmly attached to it. So in any situation whatsoever, no matter what evil manages to achieve with us, there is always some positive point. But because it is detached from its natural perspective, it takes on a negative character. So in the field of scientific research, the value of any achievement cannot be immediately questioned, but its purpose and use need to be monitored. This is for the human nous to decide.

An important element with regard to scientific research is the purpose for which it was carried out. And, naturally, the quality of the purpose invests the research with commensurate value. When the purpose is negative from the very outset, the research cannot be considered positive, nor can it be respected. Often though, particularly these days, research is respected not only as the means for some purpose, but in its own right: ‘Research for the sake of research’. Of course, it is not impossible that, even in such instances, some unexpected good might emerge, or, indeed, unintended evil. But making research autonomous in this way detaches it completely from all moral restraints.

In what we call the natural sciences, where the principle of objectivity rules, numbers and quantities predominate and, at the same time, persons and moral qualities and relationships are ignored. The same tactics are also employed frequently by the social sciences, particularly sociology, despite the fact that they focus on people and their social life. These tactics, which became prevalent in the scientific world after the triumph of the natural sciences, impair the social sciences and distance them from their real purpose. Moreover, they are an affront to the primacy of the person, which is the principle and completeness of being. If the person is marginalized, the living truth is made moribund.

The characteristic feature of the culture of our age, as of the scientific research which is being conducted within its framework is the marginalization of the person and our subjection to the impersonal whole or even to irrational nature. This neglect, which is initially presented as methodology, in the end proves to be of the essence. Modern civilization is not merely not centered on the spirit, as would be appropriate to people who stand out in the world for their spirit, but it is not even technocratic, as is often claimed. Naturally, there are always technocratic elements, just as there are other features which testify to the spiritual factor within us. But these are not merely atrophied; they are ineffective, as well.

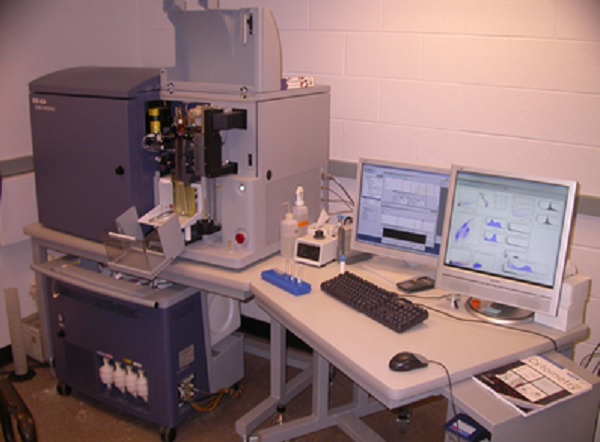

Our culture has become machine-dominated. And this domination does not lie is any increase in the power of machines, nor in the conveniences they provide us with, but in the pervasiveness of the frigid spirit they produce. It lies in the prevalence of the mechanistic logic they promote and cement. And our age is machine-centered because it shapes people ‘in the image and likeness’ of machines. It makes the heart arid, makes a machine of the mind and bulldozes our personality. All people and all their activities are reduced to numbers, described in numbers and trapped in numbers.

Yet people remain people. As long as they exist, they develop as persons. The principle of the person is the fundamental principle of the Orthodox Christian view of the human person, as, indeed, of its theology. When the person is nullified, then people no longer exist as such, nor is God worshipped as the living God. Besides, the essential feature of our creation ‘in the image of God’ is our sovereign authority. We are not subject to anything or anyone; we simply exist as a given, even for God Himself. This is why our relationship with God depends on the principle of freedom. Anything and everything which imposes on or reduces our value as persons assumes a negative value.

In this context, it is natural that we should address, as a matter of urgency, certain problems concerning the purpose and extent of the application of scientific research. But first of all, we need to pose the question asked by Socrates of the philosophers of his day who were attempting to study nature: ‘So, have these people learned what they should about human things and are now able to busy themselves with other ones, or have they abandoned human things in order to inquire into other ones, imagining that they’re doing their duty?’ [11].