On Tradition

26 February 2020It is the case that many people have expressed their own understanding and convictions regarding tradition in a variety of ways. The worst of it is that many have trampled upon it in order to promote and build upon it their own careers and selfish ambitions. It’s a subject which has been bothering me for many years now, and I confess that I’m troubled over the truth behind the precise definition and expression of the notion of ‘tradition’, both in the artistic and ecclesiastical spheres.

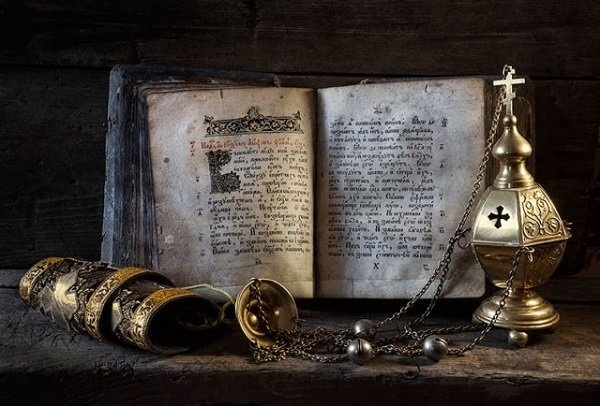

Usually, the most innocent and widespread view regarding it is that tradition is understood as an unaltered reproduction of features from the past, such as customs, arts and habits, with no correlation or reference to the present, as if they were museum objects, entirely divorced from the modern era and showcased as a valuable legacy to be preserved.

Yet it’s true that whenever something has no place in the present, it’s condemned either to be lost or to be transformed into an inanimate feature of everyday routine, devoid of any meaning for our life. A connection with the past isn’t achieved by the reproduction of certain features, but through the transferal of their ethos and deeper meaning. In brief, the ethos is more valuable than the custom because the ethos produces meaning in our everyday life and our relations with other people and the world, whereas custom simply reproduces something from the past as a performance, a spectacle, an exhibit.

Even those things we call traditions are the products and results of their contiguity in time and place. They arose from a melding of even older features in the place and time when they made their appearance and became established. So they’re products of relativism rather than absolutism. The fact that they have actually come down to us is also the result of older investment, through the lens and filter of the time when they were formed.

We ought, therefore, to define tradition not as an object, or immaterial legacy, but through our own time and place. We should attempt to seize and grasp the ethos, the experience, the values and principles of its features and imbue the elements of our everyday life with them. The vessel will change, but the contents will remain the same. As one academic put it once, there’s no point bringing a sickle into the present as a museum piece, or the place where it was used, unless you allude to the value of the fatigue, the labor and the pain of a hard life; there’s no point restoring an old couch without feeling the value of hospitality and respect and the delicacy of everything made, even a piece of furniture in everyday use.

The same is true in the sphere of the Church. It can be seen that we try to preserve the ecclesiastical arts through the mystique and veneer of the necessity to maintain tradition. But in this way we separate and elevate ecclesiastical art, be it iconography, architecture, or, more importantly, music, from the events and stimuli of the contemporary era, thus creating the impression of an alien and extraneous art. We thus deprive many devout and godly artists of the opportunity to create and to express themselves within the worship of the Church, regarding the attempt as a deviation from tradition and a potential for heresy or ecclesiastical indiscretion or hubris.

In conclusion, if we wish to be faithful followers of any historical investment and identity, we should reflect on the meaning of the word ‘tradition’. In my humble opinion, if we wish to be true and authentic, we should pore over everything valuable, eternal and beneficial we have received and use it to infuse our life with new purpose. Life and its future are not so much in need of molds and matrices from another era, as they are of content and substance. Let’s change our lives, rather than just disguise them in the costumes of another age.