An Orthodox English Saint

9 March 2020Pall Mall Gazette. 24 July 1885. p. 6.

Great interest has, it is said, been caused at Folkestone and the neighborhood by the discovery in the parish church of what are believed to be the remains of St. Eanswith, patron saint of the church and the daughter of Eadbald, one of the Saxon Kings of Kent. Some workmen, in removing the plaster from a niche in the north wall, noticed that the masonry showed signs of having been disturbed at some period, and a further search was made. Taking away a layer of rubble and broken tiles a cavity was discovered and in this a battered and corroded leaden casket, oval shaped, about eighteen inches long and twelve inches broad, the sides being about ten inches high. Within it were human remains, but in such a crumbling condition that the vicar declined to allow them to be touched except by experts. St. Eanswith lived early in the seventh century and was interred, according to historians, in the church on the cliff, where she had founded a priory.

The Guardian, 6 March 2020

Bones discovered more than a century ago in a Kent church are almost certainly the remains of an early English saint who was the granddaughter of Ethelbert, the first English king to convert to Christianity, experts have concluded.

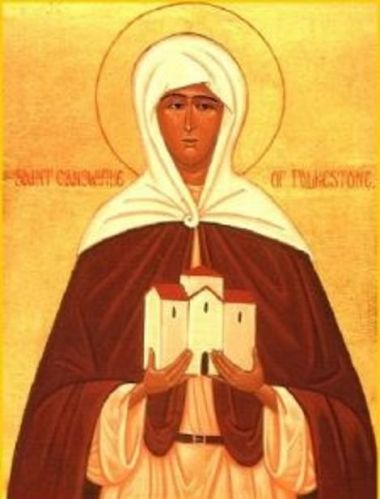

Saint Eanswythe, the patron saint of the coastal town of Folkestone, is thought to have founded one of the first monastic communities in England, probably around AD 660. She died a few years later, while still in her teens or early 20s.

Initial analysis suggested the bones were consistent with Eanswythe: they came from one person, probably female, probably aged between 17 and 20, and with no signs of malnutrition, so potentially a person with high status.

[A spokesman said that the find represented] ‘a continuous living faith tradition at Folkestone from the mid-seventh century to the present day’.

Lesley Hardy, the director of the Finding Eanswythe Project at Canterbury Christ Church University, said: ‘Folkestone is an extremely ancient place but much of its heritage has been erased through development in the 19th and 20th centuries. Eanswythe was at the centre of the community – people would have seen her as a local hero’.

There are a number of interesting features in this story. The first is the reliability of local tradition. One of the sad effects of our modern confidence in our own superiority over all the generations who went before us is that we tend to write off memories if they seem not to dovetail with our own experience. ‘What are the chances of that being true?’ And yet a similar occurrence took place not long ago at the Holy and Great Monastery of Vatopaidi on the Holy Mountain. Monastery tradition had it that there were relics embedded in a particular wall, and when repairs were being carried out, this proved to be the case.

The second, though it is not specifically mentioned here, is that the relics may well have been hidden at the time of the dissolution of the monasteries by Henry VIII. It is almost impossible to overstate the drastic repercussions of this policy. In the Middle Ages, England was held to be under the special protection of the Mother of God. Despite the formal schism between Orthodoxy and the Vatican, ordinary people in the East and West would have recognized many common features in their liturgical life. The Reformation ended that. Essentially, monasticism ceased to exist in England. For us Orthodox, this is an unimaginable situation. Not that monastics are by definition superior, but if the Church is not encouraging some of its members to devote themselves entirely to the pursuit of an exclusive relationship with Christ, at whatever cost, then something has gone wrong. We have only to look at the newly-proclaimed saints: Porfyrios Kavsokalyvitis, Païsios the Athonite, Iosif the Hesychast, Sophrony at Essex, Ieronymos Simonopetritis, Efraim Katounakiotis.

It seems that Saint Eanswith was one such person. She was the daughter of King Eadbald of Kent and the niece of Saint Ethelburga, the Christian wife of the pagan King Edwin who later converted to the faith. A nobleman or prince is reported to have asked for her hand in marriage, but she refused and founded what may have been the first women’s monastery in England. She died in her late teens or early twenties.

She refused. A young girl, the daughter of a king, who, you might think, could have been given away in a dynastic marriage, said no. By and large, this is not how, today, we see women in the past. They were oppressed, they were chattels, they did as they were told. This was certainly the case in 19th century Britain, which was the nadir of women’s rights, but it was not necessarily the case before then. The dowry is a good example. It was not, as it became, an amount of money paid to a man to take a wretched daughter off the hands of her father. It was, in fact, what the woman brought to a marriage and remained in her possession. The husband had the use of it to increase its value if he could, but the dowry itself belonged in its entirety to the wife.

Saint Eanswith appears to have been able to make her own decisions and to have had the support of her family in doing so. Without stretching the point, it is interesting that the report emerged a mere two days before International Women’s Day.

May we have her prayers and blessings.