The ‘Fool’ and the Clever Ones

4 June 2020It often happens that the internal beauty of the life of repentance and the staunch battle against sin and the passions are not immediately obvious. One such instance was the case of the nun Isidora, who lived in a monastery in Egypt and whose story we read in the Lavsaïkon (Lausaic History)*.

Isidora loved humility and simplicity and tried to live in obscurity, as far as this was possible. Alas, as often happens, the more she tried to be humble, the more the reprobates of this world saw her as a tool of exploitation. They found her laughable.

The magnificence of internal and spiritual beauty depends on the extent to which you’re able to bear up under the mockery of others. Of course, Christ advised us to be as shrewd as serpents and not simply to allow ourselves to be pushed around. When He was being interrogated by Annas and was struck by a servant, He Himself also asked why the man had done so. In the end though, He gave the ultimate example of humility when He suffered all the pain of His death upon the Cross without complaint: ‘When they reviled him, he did not revile them in return; when he suffered, he made no threats… by his wounds we have been healed’ (1 Peter 22-23). His wounds were such that He had ‘neither form nor comeliness’, but through them He not only healed our own wounds, but gave us the opportunity to acquire comeliness incomparably greater than our ‘ancient beauty’ [cf. Isaiah 53].

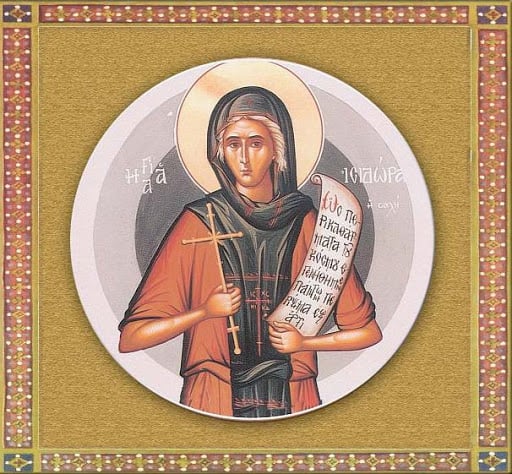

Saint Isidora

The key to the acquisition of such beauty is humility in imitation of Christ. One of the most dangerous passions we have is trying to gain fame and standing from the praise of other people. So when we know how to disregard the praise of others and to seek glory through our spiritual virtues, then our inner beauty increases.

The more we rejoice over praise from others, the more we become distorted internally, and we reach the point where we no longer care who it is who’s praising us. So we’re pleased with ourselves even if we’re praised by thieves, crooks and the villains of this world. Precisely because of her simplicity and humility, the nun Isidora became an object of scorn for the other sisters- strange as that may seem. Monasteries don’t house only praise-worthy spiritual strivers, but also idlers and malingerers.

Although some of the nuns were good, there were others who said: ‘Since the poor thing’s simple-minded and willing, let her do all the dirty work’. [‘She was called the sponge of the community’].

Even worse, there were some who mocked her for her simplicity.

Living nearby, [on Mount Porfyritis], at that time was Saint Pitirum. The fact that he was virtuous, however, didn’t prevent him from being affected by the thought that he struggled as hard as he could and wondered if there were others who strove as much as he did.

In order to help him deal with these prideful thoughts, God sent him an angel who told him: ‘You’re not the best in the world. There’s a nun in the Monastery of the Tabennisiotes who surpasses you in humility. You’ll recognize her from the crown around her head’.

So he set off to go and find her, for his own benefit, to hear a word of advice and teaching. When he entered the monastery, he asked the Abbess if he could see all the nuns, one by one. They all came but none stood out. Saint Pitirum didn’t see the inner beauty he’d been led to expect on the face of any of them. So he asked: ‘Isn’t there any other nun?’.

‘No’, said the Abbess.

‘Well, there’s one missing’, insisted the saint. ‘The one the angel indicated’.

The Abbess then said: ‘We do have another one, Abba, in the kitchen, but she’s a bit simple’.

‘Bring her here’, said the saint. So they went and found her washing the monastery’s large pots which were grimy and sticky. They had to drag her away, because she had obviously realized why they wanted her, perhaps because God had revealed the reason.

As soon as he saw her, the saint discerned the spiritual beauty of her humility, which was confirmed by the ‘crown’ she wore on her head: a piece of rag instead of a cowl!

He fell at her feet [addressed her as ‘Amma’] and asked for her blessing. She also fell at his feet and said: ‘You bless me, master’.

The other nuns were astonished and said: ‘Elder, you’re making a big mistake. She’s a fool’. The saint then addressed them and said: ‘You’re the ones who are fools. She’s better than all of you and me, too. I pray that God will find me worthy to be with her on the Day of Judgment’.

[‘This blessed woman was unable to bear the glory, praise and apologies from all the community, considering them a burden, and secretly left the monastery. And to this day, no-one knows where she went, where she hid and where she passed away’].