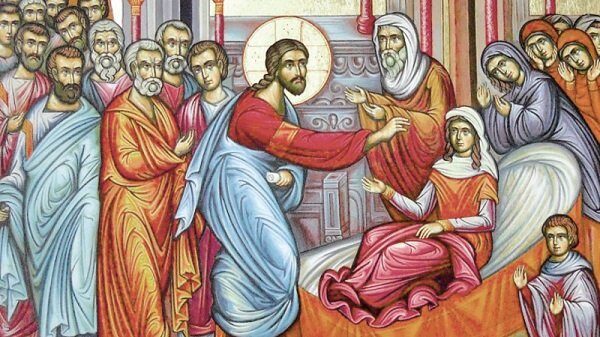

Life through Death (Luke 8, 41-56)

9 November 2020‘Do not weep. She has not died but is at rest*’. Then as now, these words of Christ challenge our reason and will always challenge us to put our trust and lay our hope in the reality of the mystery and truth of God. They invite us to look with faith at what is concealed in the dark looking-glass of death. It’s a fact that, from the moment people are born, there’s no other certainty than that they will die at some stage. And yet, this certainty is an unknown experience. We don’t have experience of our death. No-one’s lived through their biological death and can tell us what it means. Nobody can tell us what we’ll go through when we die**. Of course, Christ and the charismatic members of His Body, the saints, have revealed the farther shore of life, the real and immortal life of eternity after death.

This certainty, then, is faith and revelation; it’s another dimension to existence and life which, let’s not forget, greatly transcends our earthly experience. Here the word of God and the experience of the Church are the sole points of support for our existence; they reveal the miracle of the Resurrection and give a glimpse of the mystery of eternity. Without these, no reasoning, no science, no philosophy, no knowledge, no power of ours or of the world can illumine the darkness and resolve our predicaments. This truth tells us that death is not now the terminus, but has become, in Christ, a passing over [pesach, pascha] and transition to eternity. It’s rather like another birth, into real life.

Death isn’t something that’ll come upon us on the last day of our earthly life, but something we face every day. The way we live depends upon the manner in which we view death. Our relationship with death plays a definitive role in our way of living, in what we call our outlook on the world. This is the manner in which we understand our relationship to our self and to God, the world and life. If people accept that death is dissolution, decomposition and extinction, then they’re brought to despair and the void. In the absurdity that they’re living in order to die, they have no option but gaudeamus igitur, ‘Let us eat, drink and be merry, for tomorrow we die’.

People become selfish, cynical materialists, as is clear from their everyday behavior. For them, faith is superfluous and bizarre, morals are irrelevant and sin is a joke. The realm of the spiritual shrinks dangerously, to the point of extinction. The body and the emotions, matter and its various requirements become the ‘be all and end all’. People then need to make haste in order to enjoy the pleasures of life while they still can. Worry about the end which is impending and which will undo everything overshadows their existence. And after death, there’s nothing. This is the root of nihilism fully exposed. But fortunately for us who believe, Christ’s Resurrection is the annihilation of death and the source of life beyond the grave. The words of the Gospel indicate a life with meaning and fulfilment; they promise and guarantee for us ‘an excess of life’, a life overflowing and continuing into eternity.

My beloved brothers and sisters, the present life isn’t oppression designed to make us underestimate and reject this world, to make us long for another which we’ve never known. It’s not about desolation and disdain for all forms of beauty and joy- a distorted view which is common. It’s a struggle for the truth, faith, love and hope. It’s communication and a relationship with God and other people. Such a life circumvents the barrier of death, and then, not only are the joys and splendors of life transformed in a redemptive manner, but so, too, are the sorrows and the tears. Those of us who see life in these terms can, in Christ, view death as a sleep from which we’ll awaken at the general resurrection. Amen.