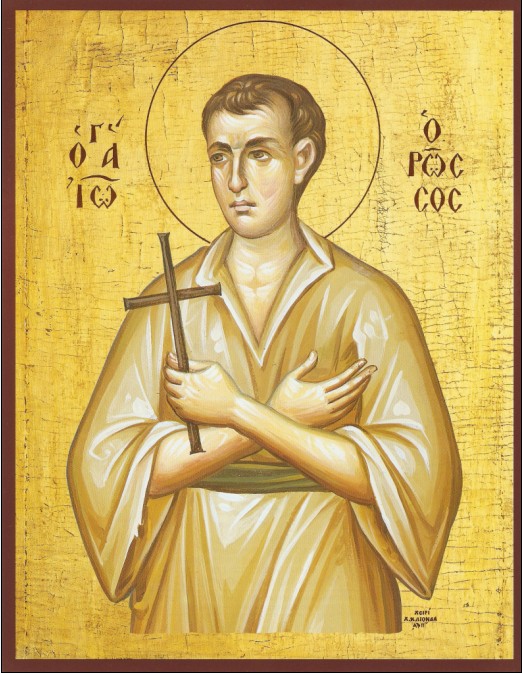

Saint John the Russian

27 May 2021For people who have any understanding of God and his kingdom, nothing’s a misfortune.

Saint John suffered one of the greatest misfortunes that can befall anyone. He was taken prisoner of war. By the Turks. At the age of twenty. What could have been worse?

Yet this misfortune proved to be his greatest good fortune. Not only did he gain the kingdom of God, the only true good fortune, but he succeeded to such an extent that he was able to share the fruits of his achievement with many others, even to this day, 200 years after his demise. In an ever-widening circle. How? Why?

He was taken prisoner with a whole group of young Russian soldiers. They were all faced with the same choice: ‘Will you become Turks? If you do, well and good. You’ll live freely with pleasures and entertainments’.

The Turks knew what they were about. They tempted the young men with sex. And many of them complied. Those who resisted the temptation of sex were taken off to be tortured. First threats. Then action. And so these others also complied. They gave in. They became Turks*.

Why? Because people want to have a pleasant life. Full of nice things. Everything that’s sweet is a pleasure. It makes life beautiful. And we call it pleasure. The sweetest pleasure for people is sex, especially if you’re a young man of twenty. Given that, is it any surprise that the young Russians complied and became Turks?

The sweetest thing is pleasure; the most bitter is pain. So bitter, so hated is it that, in order to avoid it, people are prepared to abandon each and every pleasure. Even the most enjoyable. Pain chills. The whole person. And it extinguishes all thought of and desire for pleasure. The greater the pain, the worse the effect. So is it any surprise that, in the face of pain, the young Russians converted?

We may not be surprised, but we don’t admire them. We feel sorry for them. We commiserate with them. They were unfortunate minions. Perfect lackeys. Strapping young men in body, given that they were young, brawny and vigorous. But in their soul, their mind, their will, they were minions. Nonentities.

They remind you of dogs which salivate when they’re given a morsel at the hand of their master- slaves to pleasure. Then they get a kick and run away- slaves to pain. Whenever the master calls them with the promise of a scrap, they come running. They’re such slaves to pleasure that they forget the kicks. And such slaves to pain that when they’re kicked they run away immediately. How low people can fall, slaves to pleasure and to pain.

Saint John was no minion, no slave to pain and pleasure. Nor was he merely free of them. He was something more. He was a hero of pain and pleasure. He was unmoved either by the temptation of sex or the threat of torture. Saint John was no lackey. He was a hero.

He preferred pain, however great it was, to the fate of ending up a minion. He thought: ‘Even though we may be lackeys ourselves, we have no time for minions, so how could it be possible for God to hold them in esteem?’

He entered by the narrow gate of pain and toil. He lived in a stable. But the stable shone with light, as did his soul. After his death, his body remained incorrupt, just as his mind had remained impervious to the corruption of pleasure and pain. He was a hero in his outlook. And God showed him to be heroic in his body, too. Well-built, vital, youthful to this day. And the others? They melted in the desire for pleasure; they melted in the face of pain and they melted in the body. What are they today? Nothing at all.

Saint John tells us: ‘Stop being slaves to pleasure and slaves to pain. Become heroes of pleasure and pain’.