From the humble colt of Palm Sunday to the stone of the tomb on Great Saturday

20 April 2022If, with due care and attention and in the spirit of a desire for knowledge, you follow the Biblical and hymnographical texts of the Orthodox Church, in an effort to proceed towards the passion and the resurrection, it’s impossible to miss the intense participatory presence and expression of the natural world.

This mobilization of animals, plants and matter in such a significant period of time as Great Week is no coincidence. On the one hand, it marks the close connection between nature and humankind and, on the other, the firm commitment on the part of the Church to employ all kinds of indirect ways to awaken prodigal and suffering people and bring them back to the redemption of a return to their father’s house, though, in doing so, it respects completely the freedom which God has given to his rational creations. Since some of us may not have had the opportunity to notice and evaluate this important parameter, we’ve made an effort to record a sketch of it, so as to facilitate Tradition in the transmission of its message in today’s anthropocentric and extremely rational reality.

On Palm Sunday, then, nature makes its presence felt through both the colt and the palms. The colt serves as the earthly throne of Christ the King and also as the necessarily humble vehicle for his triumphal entry into Jerusalem. The message is clear: without humility we can’t take part in the passion nor in the Resurrection. Meanwhile, the branches of palms in the hands of the people are the required accessories for the reception, glorification and apotheosis of the Messiah and mark the close connection and companionship between humankind and nature.

On Great Monday, the negative model is highlighted of the fig-tree which, because it had only leaves and no fruit, was dried up. This image points to the fate of those who refuse to show fruits worthy of repentance.

On Great Tuesday, natural images are presented which have very different significances: a) the thirty pieces of silver of the betrayal by Judas are testimony to the disastrous consequences of impiety and avarice; b) the hewn fig tree indicates the consequences for those who are cut off from the body of Christ; c) the extinguished lamps of the five foolish virgins represent the slothful and uncharitable life, spiritual stagnation and disorder; d) the lit lamps of the five wise virgins direct us to the life of virtue, spiritual readiness and vigilance, good works, and the use of talents for the public good; e) the goats depict the coarseness of sin, a dissolute life and a place on the left of the Father; f) the sheep symbolize those who faithfully follow Christ the shepherd and are therefore placed on the right; g) the garment which, depending on its quality, that is whether it expresses dishonor or glory, is either a means of exclusion from or entry into the ‘spiritual feast of the bridal-chamber’.

Great Wednesday is dominated, on the one hand, by the image of the tears of the harlot, evidence of her great repentance and also hatred of disgusting sin and the pleasures of the body, and, on the other, by the image of the precious myrrh with which she anointed the feet of Jesus, prefiguring the myrrh of the burial rite and symbolizing genuine and practical repentance.

The hymns of Vespers and the Divine Liturgy on Great Thursday are dominated by the images of: a) the blameless and innocent lamb being led to the slaughter; b) the vipers, of which Judas and the Pharisees are named as offspring, in order to display their ingratitude towards their benefactor; c) the bread and wine which, in accordance with tradition, are used at the sacrament of the Holy Eucharist at the Last Supper, depicting the Body and Blood of Christ; d) the water in the basin which Jesus used to wash the feet of the disciples, teaching them humility and the spirit of ministry; e) the garden of Gethsemane, which became a place of prayer and was witness to the heedlessness of the disciples, the preparation for the passion and the betrayal of the Teacher; f) the cockerel, which. by crowing three times, reminded Peter of the warning Christ gave him and thus engendered within him a sobering awareness of his betrayal.

At the service of the Passion, attention is focused mainly on the tree of the Cross, while the picture is completed with the crown of thorns which was devised by those who crucified Christ in order to mock him ‘who painted the earth with blooms’, with the spear, the nails and the artificial purple. As regards the tree on which Christ was to be crucified, folk tradition has it that it wasn’t the product of consent on the part of nature, but of betrayal. When the plants heard that Christ had been condemned, they gathered together at night and agreed among themselves that not one of them would agree to be made into a cross. But, as was the case with Judas, a single tree, a kind of oak, broke the agreement, which resulted in its being anathematized by all the other trees and cast out. This is a myth, but is also another example which goes to prove in a vivid manner the reaction of nature to the impious choices of human beings.

The hymn-writer takes the opportunity to contrast the tree of the cross which brought the robber to paradise with the tree of Adam which became the reason why he lost paradise. He also contrasts the manna and water in the wilderness with the gall and vinegar which the crucifiers offered to their benefactor. He also describes Christ’s bloody side as a fountain of life, as a spring which brings forth the Church and waters rational paradise. It’s the same as the pelican which, from its wounded side drips reviving streams onto its dead offspring, bringing them back to life.

Also impressive is the reaction of nature, which is depicted as trembling. The earth is horrified, its foundations are shaken by divine fear, the bright stars are darkened, day is turned into night, the curtain in the temple is torn in two, the mountains are afraid, the sea retreats, rocks are split, the graves open and the dead emerge. This goes to show that ‘all things suffered with him who created everything’.

At the morning service and Vespers on Great Friday and also at Mattins on Great Saturday, the main image is that of the burial. The earth ‘shelters’ and embraces the Lord of glory, the nature of whose divinity remains indescribable and indefinable. It holds within it him who holds in the palm of his hand the whole of creation and it sings its own funeral hymns. Joseph and Nicodemus borrow myrrh and perfumes from nature in order to bury Jesus’ body in the best possible way.

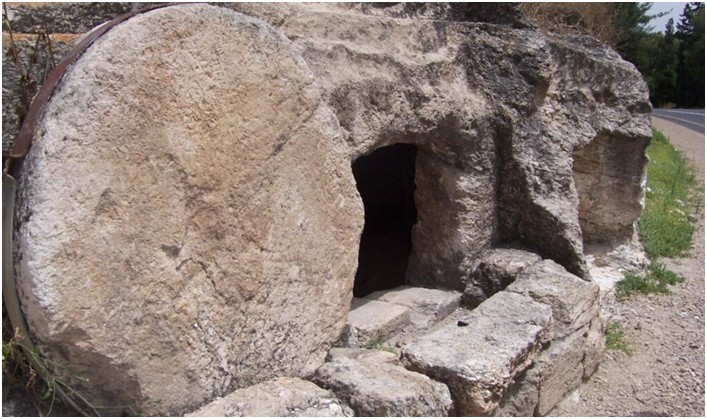

The picture is completed with the massive stone used by the guards to ensure a secure seal on the entrance to the grave and to cover him who, with his virtue, covers the heavens, as the hymnographer points out.

Unlike people, who are miserable and unwelcoming, the grave is described as being ‘jubilant’ because it receives the Creator as if he were sleeping, because it provides hospitality to the ‘stranger’, the man estranged from other people. It’s transformed from a grave of death to a grave of life and resurrection, a divine treasury of life, a source of arising. This is why it’s justly called ‘life-receiving, life-providing, life-giving and all-holy’, while it’s been established as the center of the Church of the Resurrection and a pilgrimage site for the whole of Christianity.

In the end, the earthly course of Christ as God and human person begins and ends in the bowels of the earth, a long way from palaces and other prominent cultural structures. He was born in a cave and died in a grave.