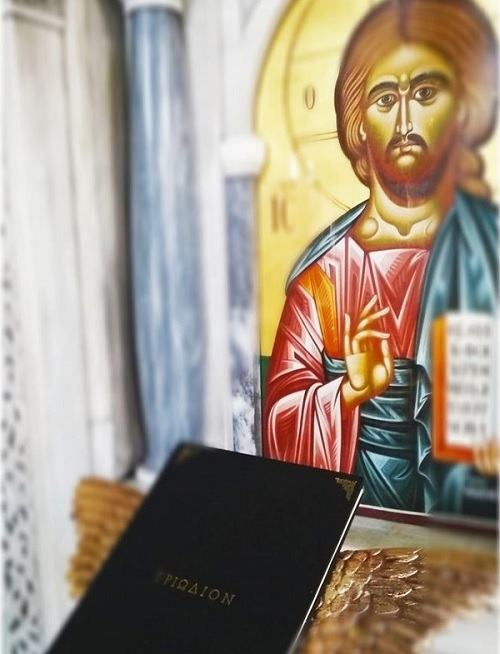

Let’s open the Triodio with humility

10 February 2023The Church doesn’t leave us without consolation. One feast follows another and all together they contribute progressively to the common goal which is our spiritual and mental enhancement and, in the end, our salvation. As the ancient Greeks said: ‘A life without feasts is a long road without inns’.

The feast of the Reception and the blessing of Mary after forty days complete the festal cycle of Christmas and therewith the liturgical cycle of the unmovable feasts. After this, with the opening of the Triodio, there follows a new liturgical period, that of the moveable feasts, which brings us to the supreme event of the Lord’s resurrection and, God willing, our own resurrection with him.

So this is why we say that the Church, through the wise Fathers and the inspired hymnographers doesn’t leave us without spiritual nourishment, without lessons and messages about our salvation, which means that we have no justification if we say that we were ignorant or that we had no signposts to show us the way. Even when we stumble, when we slip backwards and sometimes fall or go astray, with good intent and in the right conditions we can still find the strength to straighten ourselves out and continue on the path to salvation. Only if we insist and persist stubbornly in our relapse have we got no defence because, ‘to fall is human, to remain in sin is satanic, to repent is divine’ (Saint John Chrysostom).

At the beginning of the Triodio, the Church places one such instructive example for our spiritual edification, with the reference to two representative types, the Pharisee and the Publican, who aren’t given names, precisely because the parable is about characters whose respective patterns of behavior are either praised or condemned.

This is apparent from the hymns of the day, which ‘interpret’ poetically the readings, enriching their content, moreover, with words of the Fathers. In the troparia, particularly those of the Matins canon, a contrast is drawn, through emphatic and richly expressive forms, between the arrogance and vanity of the pharisee, on the one hand, and the humility and contrition of the publican on the other.

According to this instructive excerpt, (Luke, 18, 10-14), ‘two men went up into the sanctuary to pray’. But one of them, the pharisee, ‘stood and prayed to himself’; in other words his reference point wasn’t God but himself. A modern, punctilious, religiously-minded person, like the pharisee in his day, might ask in surprise: ‘But doesn’t God care whether I perform my religious duties; whether I fast, offer help to other people, go to confession and take communion?’.

The answer to the pharisee in the reading and to all ‘pharisees of duty’ has been given very aptly by our illumined saints throughout the centuries. I’d mention two examples to illustrate this. The first is from the Old Testament, where the Lord, arguing with his people through the mouth of the prophet Isaiah, says pointedly that he isn’t interested in sacrifices, in fasts, in honors, and intercessions, which he hates and from which he averts his eyes. If the people want him to listen they have to fulfil certain basic requirements: they must be cleansed of their wickednesses; do good, which means rescuing the oppressed and defending widows and orphans and, in general, seeking his righteous judgement. Isaiah/the Lord ends by saying: ‘If you are willing and obedient, you shall eat the good of the land; but if you refuse and rebel, you shall be devoured by the sword’ (Is. 1, 10-20).

And then, Saint Ephraim the Syrian has this to say to Christians who observe forms rather than the essence: ‘all ascetic effort, all self-restraint… and wealth of knowledge is in vain in the absence of humility’ (Ephraim the Syrian, ‘On the expulsion of pride’, Works, vol. 1).

Besides, the Lord himself addressed the pharisees with those dread sentences beginning with ‘Woe’, condemning their hypocritical behavior, their wickedness and callousness to the detriment of the people. ‘On the outside you appear righteous to others; but on the inside you are full of hypocrisy and iniquity’ (Matt. 23, 28). Indeed, he warns them: ‘The greatest among you will be your servant. All who exalt themselves will be humbled, and all who humble themselves will be exalted’ (ibid, 11-12). Moreover, the greatest example of humility was given by the Lord himself, with his ultimate ‘poverty’: although he is God, he nevertheless took on ‘the form of a servant’ and, indeed, became ‘obedient unto death’ for our salvation.

As opposed to the boastful and self-satisfied pharisee, who feels superior because of the humble station of other people ‘I am not like the rest of the people…’, Saint Luke and the Church highlight case of the sinful but humble tax collector, who cries to the Lord with compunction: ‘God, be merciful to me, sinner that I am’. What a contrast in manner and manners. One stands there haughtily and demands recognition; the other stands to one side, not daring so much as to raise his eyes to heaven ‘because of the multitude of his sins’ and seeking only the Lord’s mercy.

For the Lord of mercy and love didn’t come into the world to call the righteous, those ‘who trusted in themselves that they were righteous and regarded others with contempt’ (Luke 18, 9), like the pharisee; instead, he came to call ‘sinners to repentance’, which is why he justified the sinful but sincerely repentant publican, rather than the formally virtuous but hypocritical pharisee.

The message from this first, instructive extract from the Triodio is clear: if we, in our turn, wish to find grace and mercy from the only true and righteous judge, our Lord and God, all we have to do is follow the example of the publican, who, acknowledging ‘the multitude of his sins’, sought, with contrition, the Lord’s mercy: ‘Lord be merciful to me, sinner that I am, and have mercy on me’.

Certainly the Lord knows the difficulties involved in repentance but he also respects sincere intent- provided it’s really sincere- and doesn’t regard the penitent with contempt. This is why he ‘opposes the proud, but gives grace to the humble’ (James 4, 6). It’s also why the Fathers consider humility the supreme virtue and call it ‘elevating’, because it raises us up in the eyes of the Lord- not of other people- and exalts us before him.

Let’s take the first step, then, and acquire a sense of our sinfulness, and let’s repair our relationship with God and other people, since these are the necessary requirements for us to continue our spiritual struggle. Then, with his grace and mercy, the Lord will supply anything that’s missing.

This, in any case, is the meaning of the penitential Triodio: that we should repent sincerely and advance spiritually, living ‘prudently, righteously and devoutly’, regaining the paradise which was lost to us through our disobedience and lack of repentance.

Therefore, ‘let us humble ourselves’, ‘let us offer to the Lord the publican’s sighs’, so that we may be granted salvation by the only Lord and Savior, who gives remission and eternal redemption ‘to all penitents’. Amen.

A good spiritual Triodio, with compunction and humility.