Love and Mourning in the Human Race (2)

25 July 2023[Previous post here]

Grief has its own stages. According to the psychological approach [1], we need to pass through them with care and support. We need time to begin to discover meaning in everything that’s happening to us. With Magdalene, it didn’t take much time. Christ appeared to her and told her about the resurrection. With this faith, she then continued her life, which had acquired a different meaning. And, as far as we’re able, we should ask God to give us self-knowledge and acceptance, some sense of his presence, so that we can come through grief and reach a meaning. We should ask that we may discover his providence so that our soul can rest more easily and that the fire of pain may be extinguished.

In the life of the saint, we experience her steadfast love in all situations. This is why Saint Maximos, in his first text, says that, in order to achieve a stable disposition, we should be interested in only the absolutely necessary earthly things, so that we’re not dependent on anything. Dependence prevents us from being free and so- whether we want to or not- we’re unable to have stability within us.

One concern for ourselves and our soul is to pay attention to what’s preventing us from achieving this stability. This is a profitable form of reflection which involves an internal process which may entail effort and pain. But the worth of other people, the value of every soul that God has brought into our path, is sacred, and it’s worth the effort to turn in upon ourselves and see what it is that’s broken in our relationship with them.

According to her paraclitic canon, Saint Mary had a reverential boldness towards Christ, and this is a feature of steadfast love. Steadfast love is always present in a discussion, it knows no fear, it doesn’t evade and it’s secure in the relationship. Magdalene came, searched, wept and sought: ‘Where are you, teacher?’. As the late Elder Aimilianos writes in his book On Sobriety [2], monastics seek everything from their Elder and this is done within a climate of reverential boldness. Nothing is withheld. They know the spiritual context, they’re aware of the boundaries and are conscious of the fact that the revelation of their inner world has their well-being as its aim. This is a healthy spiritual/therapeutic relationship.

‘Dispassion engenders love, hope in God engenders dispassion, and patience and forbearance engender hope in God; these in turn are the product of complete self-control, which itself springs from fear of God. Fear of God is the result of faith in God’ (Saint Maximos the Confessor, 2nd Text of the First Four Hundred on Love). Here we find ourselves face to face with an awesome spiritual analysis regarding the mysteries of the human soul which is linked to God and is striving spiritually. Pure love is engendered by dispassion. Dispassion allows nothing to intrude between the soul and God, to interfere with communication with him. And a sign of dispassion is that we see the image of God in every human being, as we said earlier when affirming the value of each person. We love without pathological passion, that is, we love in the good sense of passion. We love without doing harm to ourselves or to others in the name of pathological love. We love through the Holy Spirit, with love in Christ. Unconditional love without limits. We love and find room for others as images of God. We love without collapsing from grief or a loss because we know that we depend solely on the grace of the Holy Spirit. The relationship doesn’t end in the coffin. In our faith and in the teaching of the Fathers, grief and every trial are transformed into a blessing.

Dispassion is engendered by hope in God. Hope in God is different from the concept of hope without God. Here it means that we surrender to God, trusting in his providence. In this way, we aren’t attached to anything, we’re free, we’re poor and, at the same time, we’re rich in Christ, as Saint Paul says: ‘Sorrowful, yet always rejoicing; poor, yet making many rich; having nothing, and yet possessing everything’ (2 Cor. 6, 10). This is the hope that nothing is lost on earth, that everything is under God’s care: our pains, our tears, everything is the building material from which we build our home above. Our hope is that God will supply everything, but not necessarily here on earth. We’ll continue to receive in our other homeland above. Our basic hope is that his promise is steadfast and true.

Patience and forbearance lead us to acquire hope in God, to detach ourselves from various trivialities, to make the best of our time and to retain only that which enriches the ground of our soul to ensure a better planting. Indeed, it’s a long journey. But it’s beautiful. What could be more beautiful than to come to know the sweet presence of the Holy Spirit, the beauty of our self and, in all likelihood, the beauty of other people? Certainly the journey requires patience and forbearance, in other words it needs care and vigilance, with recognition and observation. It requires calm and awareness of our own needs and those of others. ‘Glory to your forbearance, Lord’, as we sing in Great Week. Christ’s forbearance doesn’t imply ignorance or weakness. On the contrary, it hides power and great wisdom. Very often, silence is great wisdom, especially when the other person isn’t in a position to understand or to hear. It requires love with dispassion because room has to be found for both. Christ never turned anyone out. Even to those who crucified him, he showed understanding and forbearance, because he was aware that they knew no better. And so he teaches us his own forbearance. Forbearance towards ourselves and others. We often need forbearance towards ourselves, to learn to love ourselves. It’s healthy to devote time to our garden and also to those of others, recognizing that we all suffer from abrupt changes, because life can bring us a lot of things quite suddenly.

Self-control is engendered by patience and forbearance. Through the word self-control the soul knows that it came from the earth and to the earth it will return. Self-control makes us continue to look at things in a spiritual manner. Our coming into the world didn’t depend on us, nor will our exit from it, either. Self-control in itself is a word that belongs to a spiritual and heavenly realm. It’s limited by what we mentioned before: that we should live on what’s sufficient for us. We should live in the spirit that there are others on the planet, besides us. Fear of God comes from self-control. We live with fear of God, with the justice of God. Not with a phobia or fear of punishment. But we acknowledge God’s existence. We should be aware of our limitations. Fear of God is apparent when we know that whatever God has granted us is so that we can have life, and a better life. But when we don’t live with fear of God, we’ll reap what we see and hear happening in our societies.

The circle of his analysis closes with faith. Saint Maximos began with love and ends with faith, faith in God’s grace in our everyday life. Faith in the strength he’s put within us. Faith in the strength of others. Faith in whatever he has bestowed upon us. Faith in his wisdom. Faith in his providence and his care for our salvation. Love, hope and faith. And the greatest of all, as Saint Paul says, is love. Love is the only reason we should dedicate ourselves to Christ and follow him. Faith releases us from all dependence. Because, as Christ says, with faith we move mountains. If we understand the manner in which our faith works and what’s necessary to steady it, this will be of great assistance to us.

Love, hope and faith constitute a triangle of salvation for dealing with grief. If we make provision for having space within us for this triangle, our life will be of a different quality in our pains and tribulations.

Saint Mary Magdalene is a living example of all of this. We know little about her, though we do know about her change and her being cured of the seven demons. But she filled her soul with the presence of her teacher, so that no demon could enter. She lived with steadfast love on the path of the struggle, until she reached dispassion and sanctity.

We all have our demons and passions. Let us take this stability of the saint as an example of looking steadfastly at the center of our life, at Christ. Because when we all of us together look towards the center, we’ll draw closer to one another. This is the good disposition in our relationship with Christ, with the saints and with other people.

May Saint Mary Magdalene intercede for us that we may permanently acquire this love within us. Amen.

[1] David Kessler, Finding Meaning: The Sixth Stage of Grief.

[2] Περί Νήψεως, p. 192.

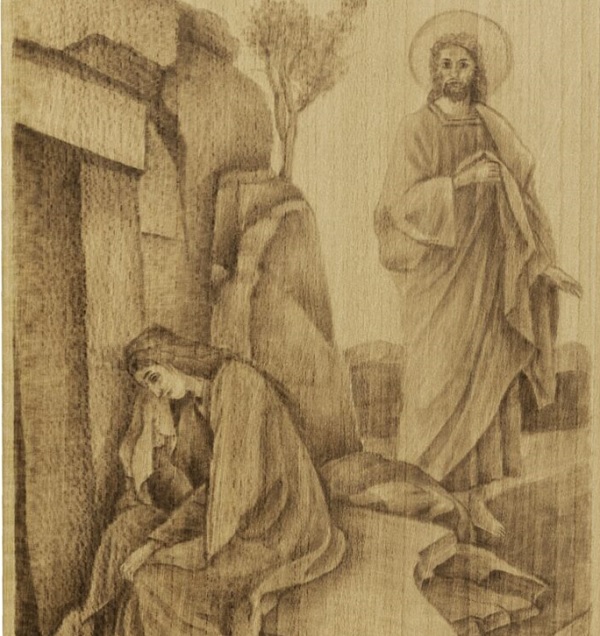

The pyrograph depicted is from the workshop of the Holy Skete of Saint Mary Magdalene, in Liti, Langadas.