The Orthodox Church of Greece and the Economic Crisis

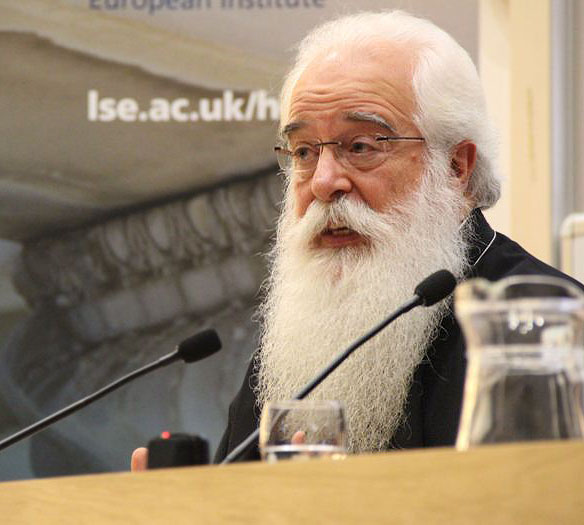

19 November 2014On November 12th a Public Lecture, organized by the Hellenic Observatory of the London School of Economics (LSE), was delivered by His Eminence Metropolitan Ignatius of Demetrias, on the theme “The Orthodox Church of Greece and the Economic Crisis”. The Metropolitan was introduced by the Director of the Hellenic Observatory Professor Kevin Featherstone, who also moderated the event. Historically a central pole of national identity, the way in which the Orthodox Church of Greece is impacted by Greece’s economic crisis and how it responds to it, is of major importance to the nation’s public and social affairs. In his lecture, Metropolitan Ignatius, after briefly describing the tragic consequences of the economic crisis on the lives of the Greek people and outlining some basic aspects of the different theo-political understanding offered by the Church, he described some specific actions that the Church has implemented from the beginning of the crisis in response to the urgent needs and challenges of the people, while he did not avoid a sincere attitude of self-criticism for the “wrongs” which, unfortunately, found their way even into the body of the Church.

Metropolitan Ignatius of Demetrias

You can read the lecture of Metropolitan Ignatius here:

For several years now, the economic crisis has remained at the center of international interest, affecting in a particularly negative way the daily lives of thousands of people, even in the very heart of the industrialized Western world. As we all know, one of the European countries most affected by the crisis has been Greece, which has experienced it from its beginning, and continues to experience the tragic consequences of this unprecedented global situation, which has sorely tried the Greek people’s social cohesion and unity, and led to hopelessness and despair for many. Thus, according to many experts, we are dealing not only with an economic crisis but also a humanitarian one, with serious consequences for people’s lives and for social cohesion. Official surveys conducted by different government institutions and economic institutes paint a bleak picture: about 1.5 million unemployed (out of a total population of 11 million), i.e., approximately 27% of the total active workforce. Among young people, the news is even worse, with the unemployment rate for people under 30 at an astronomical 60%, a figure unprecedented in the Eurozone. According to the same surveys, since the beginning of the crisis, Greeks have lost 30-40% of their income. And a recent report from Eurostat for the year 2013 lays out the tragic figures of the crisis in a particularly vivid way: 35.7% of the population (i.e., 3.9 million people!) lives close to the poverty line, 23.1% survives on a meager income in spite of the various social benefits that are provided, and 20.3% is unable to cover the expenses for the most important material goods (i.e., heating, debt repayment, a diet with meat, fish every two days, etc.). At the same time, another recent report, this time by UNICEF, reveals that “about 750,000 children in Greece are living in poverty and many of them are malnourished,” highlighting another aspect of the various problems brought about by the economic crisis, with the victims this time being children of school age.

For its part, the Church, the largest and most important locus of volunteer work in Greece, has mightily struggled to perform its philanthropic work, since the growing impoverishment of large swaths of the population has resulted in a dramatic reduction in the faithful’s contributions, on which the Church primarily relies for its social and philanthropic work.

Of course, one may wonder whether the Church can or should be involved in political and economic issues, such as the financial and debt crisis plaguing Europe—whether, in other words, the Church, which has a spiritual mission, should deal with worldly problems and issues. Such an objection, however, while legitimate, faces two problems: first, it ignores the fact that the current economic crisis has serious consequences for all Greek citizens and therefore for the Church’s flock; secondly, it seems to forget the very identity and mission of the Church which is best encapsulated in the biblical “in the world, but not of the world,” i.e., the dialectic between history and eschatology.

Having said this, one by no means wishes to suggest that one can shape economic and social policies better than the Greek state or the European Union; it is simply wished, in response to the kind invitation of this august academic institution, to share you with some reflections on the economic crisis, as well as provide you with a picture of the response of the Orthodox Church in Greece to its dramatic consequences. My position stems from my pastoral concern and my theological orientation, and is not intended to offer easy answers or ready-made solutions to all our problems. On the contrary, with a humble sense of responsibility as a bishop of the Church of Christ, an attempt will be made to lay out some parameters for a different approach to the economy, which places at its center the human being made in the image of God, and not the homo economicus who is ruled by finances and consumerism. In the remainder of this talk, some basic aspects of this different theo-political understanding will be briefly outlined, (e.g. the selection made by the early Christians of the political term “ecclesia” to identify themselves, a term borrowed from the political practice of ancient Athenian democracy, in order to emphasize their awareness of belonging to a body, a community and a society, the social and political dimension of the mystery of the Eucharist, the necessity the Church, if it wishes to be faithful to His example, not just preach to the poor, the hungry, the foreigner, and the marginalized, but must become incarnate and identified with Him and His cross, as heavy as it may be, the new meaning of life etc.) and some specific actions that the Church has implemented from the beginning of the crisis in response to the urgent needs and challenges of our people will be described (e.g. the Church has set up soup kitchens and food distribution, given out clothing and shelter, and provided financial aid, medicine, and free medical care, its contribution through its parishes, that constitute the oldest, largest, and most active volunteer network and social welfare system, which extends even to the furthest reaches of Greek territory, the most isolated village or island, where the state itself is often absent, unable to fulfill even its basic medical obligations, the program to equip and operate soup kitchens and food banks, the free Medical Clinics and Medicine, the Citizens Advice Centers, Psychological support for victims of the crisis, etc.).

The overall picture, however, would not be complete if not accompanied by a sincere attitude of self-criticism for the “wrongs” which, unfortunately, found their way even into the body of the Church (e.g. a lack of the ecclesiastical ethos of self-reproach and self-criticism). It should be admitted that some clergy and officers of the Church have enjoyed luxurious living and cozy relationships with state power, and that this has resulted in their bureaucratization and professionalization. At the same time this proximity to power did not allow us to sufficiently distance ourselves from the patron/client mindset, from populism, and from the corruption of the Greek political system, so that we could warn the people about where we were heading with the deeply parasitic nature of the Greek economy and our consumeristic absurdity, which was funded by over-borrowing and the long-term mortgaging (and consequent destruction) of our country’s future, a lack of a more critical attitude toward the problem, an attitude which, faithful to the example of the Fathers, would examine the problem at its root and not just superficially, looking at the structures that produce poverty and social injustice and not just the symptoms, etc.). The faithful Christians, are called not only to denounce the domination of the markets and social evil, but first and foremost to examine their own mistakes and omissions, and become united for the good of our social cohesion; ultimately, they must also become creative, proposing realistic steps for exiting the crisis and for a spiritual restoration of the human person. At the end of this talk, the new challenges brought about by the current crisis, they will be addressed in a spirit of dialogue, including among others, the issue of the Church’s role in the Greek public sphere (e.g. the rise across Europe of neo-Nazism

and fascism constitutes a broader threat and challenge for the Orthodox Church itself, to the extent that the reception and acceptance of the Other, especially the poor and the foreigner, is a fundamental element of its own tradition and identity, the crisis and the Church’s extensive social work—rendered without regard to religion or ethnicity—has led to a better relationship and understanding with the secular and leftist intelligentsia, who now see the Church’s contribution to society in a better light, one of the measures, for the fiscal consolidation of the Greek economy has been the drastic reduction of new civil servants. Since the Orthodox clergy are civil servants and paid by the state, an obligation arising from the confiscation of Church property, this specific restrictive measure has had a direct impact on the Church, which is now required to find alternative ways to staff parishes and pay the clergy, etc.).

The economic crisis is a reality that, it seems, will haunt us for some time to come. Despite our shortcomings, the Church has nevertheless played an important role in stemming the effects of this crisis, using every means at its disposal to provide an enormous amount of charitable and social work. What the Church needs to do now is further highlight, within the public sphere, the primacy of freedom and human dignity, as a universal and fundamental fact of human existence, in direct opposition to the logic of market domination and profit that transforms the human person into a disposable economic unit.

During their stay in London, His Eminence Metropolitan Ignatius and his associates were warmly received by His Eminence Archbishop of Thyateira and Great Britain Gregorios (Ecumenical Patriachate), the Anglican Bishop of London the Rt Revd & Rt Hon Richard Chartres, and Fr. Alexander Fostiropoulos, Orthodox priest of the Exarchate of the parishes of Russian origin (Ecumenical Patriarchate), and Orthodox chaplain of King’s College and London School of Economics.

Source: imd.gr