Unveil my Eyes

1 December 2019The cure of the blind man in Jericho is the last miracle Saint Luke relates before Christ’s entry into Jerusalem and His path towards His Passion. And it may be no coincidence that on Great Friday the hymnographer puts into Christ’s mouth the bitter complaint which begins: ‘My people, what have I done to you? How have I wearied you? I gave light to your blind…What have I done to you and how have you repaid me?’ [Antiphon 12].

The solid food of pain

Christ was crucified for blind, poor and ungrateful humankind. This is why He came: to give light to the blind and enrich us with the inexhaustible treasures of His gifts. He didn’t impose these gifts on us, however. You can’t impose something on someone who boasts that they’re wealthy and have no need of anyone else, even if, in reality, they’re wretched, miserable, poverty-stricken and blind. You can only advise them to put ointment in their eyes so they can see (cf. Rev. 3, 17-18).

It would seem that the blind man in Jericho used such ointment, because he was anxious to learn the law of God and the words of the Prophets. He was therefore free of a false sense of security and boastfulness, which isn’t necessarily true of all those who are in dire straits. Strange as it may seem, trials not infrequently bring with them haughtiness and lead to brazenness and arrogance. Sometimes accompanied by blasphemy. The solid food of pain nourishes healthy stomachs, but causes vomiting in ones which are sick.

The blind man in today’s Gospel reading certainly had a healthy stomach. He’d allowed pain to heal him and to mature him to such a ‘measure of stature’ that, when he was told about Christ’s teaching and miracles, he recognized the Messiah in His person. This is why, when he heard that Jesus was walking along the street where he was begging, he started shouting: ‘Jesus, Son of David, have mercy on me’.

The need to work together

His cries bothered the crowd, however. It was wrong for someone whom Jewish society considered unclean to cause such a scene. They were also put out by the fact that this blind, discarded man- unlike the rest of them- saw the Messiah in the person of Christ. Whereas they merely told him that Jesus the Nazarene was walking past, he called Him ‘Son of David’. Everyone knew that the Messiah would be of the house of David. Not all of them, however, were convinced that Jesus was the Messiah for whom they were waiting. Some, in fact, didn’t even want to hear of him. Be that as it may, they were all irritated by the shouts of the blind man, which is why they told him to be quiet. He ignored them, however, and began to shout even more.

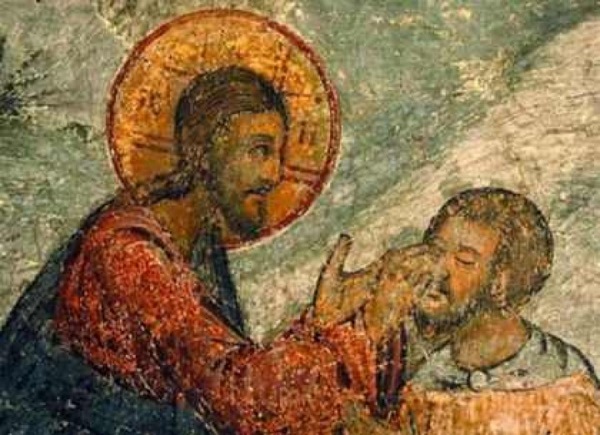

His firm and ardent faith moved Christ and He asked for the man to be brought to Him. In order that the crowd should understand that the man wasn’t asking for money but his sight, the Lord asked: ‘What do you want me to do for you?’ ‘I want to see again’, the blind man said. And Christ restored his sight with the imperious words: ‘Receive your sight’. And, moreover, He commended the man’s faith: ‘Your faith has saved you’.

The salvation of the blind man wasn’t just the healing of the eyes of his body. Saint Cyril of Alexandria stresses that ‘Christ freed him from two kinds of blindness: that of the body and that of the nous and heart’. The restoration of his corporeal sight is exclusively a gift of God. But the healing of his spiritual sight demanded the free co-operation of the man himself. It needed a great deal of effort, over time, directed towards purification and repentance and it’s this that makes us receptive to divine illumination. It’s no coincidence that, in the Old Testament the term ‘those who see’ referred to the prophets who saw God.

Why do ‘those who see’ bother people?

People who see God clearly and walk in His light are, without wishing to be, annoying to others who ‘loved darkness more’ and who ‘doing evil, hate the light’ (Jn. 3, 19, 21). The life of those who see God is a rebuke to those who walk in darkness. This truth is described aptly in the short story The Country of the Blind by the English writer H. G. Wells: a young man finds refuge among a tribe of people blind from birth. He quickly realizes that the habits, movements and general behavior of the people is very different from his own way of life and this begins to trouble him. He’s taken to the doctors of the tribe. The oldest and wisest of them gives as his diagnosis that he’s been influenced by his brain because the curious bulbous things he has in his face (his eyes) have become diseased. He suggests a surgical operation to remove them so that the man can become well and a truly law-abiding citizen.

This is a myth that we encounter in a number of different versions in world literature and, in essence, confirms what we read in the Wisdom of Solomon (2, 12-15): ‘The righteous are no use to us. They oppose what we do. They chastise us and blame us for contravening the law… Their very presence annoys us’.

For us, those who see and are righteous aren’t merely useful. They’re our trusted guides. It’s only thus that we can sing with the Prophet David, who saw God: ‘I am a companion of all them that fear you and of them that keep your commandments… Unveil my eyes, and I shall perceive the wonderful things of your’ law (Ps. 118, 63, 18).