The Three Keys

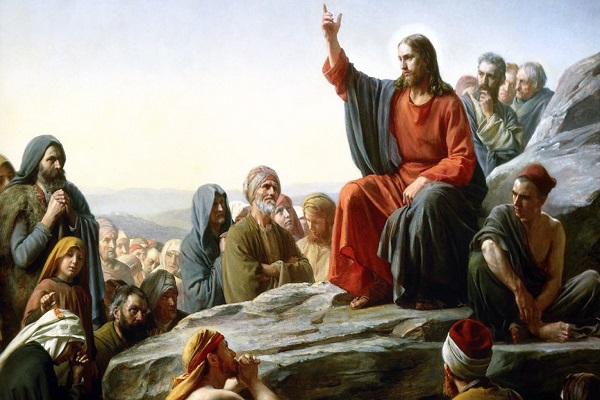

3 March 2020In Cheesefare Sunday’s Gospel, the Church takes three pieces of gold from the Sermon on the Mount and gives them to us to make keys to open the door of Great Lent.

a. Forgiveness of those who have wronged us

The first key is our willingness to forgive those who have wronged us in any way. In essence, Christ is repeating here what He said in the Lord’s prayer (Matth. 6, 12): ‘Forgive us our debts as we forgive our debtors’. As we see, the purpose of the commandment to forgive those who have wronged us is not the improvement of our social profile, nor even peaceful co-existence with other people. Before all else it’s a call to be like Christ. The aim is to teach us how to love, as Christ does. On the Cross, He forgave us, who crucified Him. And if we open our love to others, even to our enemies, in imitation of Him, Christ responds with forgiveness of our own sins. In other words, with our salvation.

As we enter Great Lent, we start a journey that will end with veneration of the Passion of Christ, Who was crucified for our sins and with the objective of forgiving them. He took our sins upon Himself, not merely to relieve us but to liberate us from their dire consequences: decay, death and our complete separation from Him. Now that we’re preparing to venerate Him, Christ calls upon us to work together with Him for this saving deliverance, by bearing the easy burden, on our part, of forgiving the trespasses of others.

This collaboration, which is so great an honor for us and so necessary for our salvation, demonstrates the excess of God’s loving-kindness towards us, according to one commentator. Christ makes us masters of the remission of our sins. Whether our sins will be forgiven no longer depends on God but also on us. To the degree that we forgive others, He will forgive us.

b. True fasting

The second necessary key for us to enter Great Lent with joy is the proper practice of fasting. The commandment to fast, which was given by God as early as the Law of Moses, doesn’t aim at self-promotion and display, nor today’s much-vaunted preservation of health. Fasting is the voluntary reining in of our egocentric, carnal outlook so that we can express our love and gratitude to Christ. We thank Him Who not only fasted strictly but also suffered death on the Cross in order to bring us the Resurrection of our bodies. We fast out of obedience and love towards Christ. Here, too, Christ stresses that obedience to His will is acceptable to Him when it is performed without hypocrisy or any disposition towards self-aggrandizement. The preening and false gloom of the Pharisee have nothing in common with the Publican’s humility and repentance, which are the aims of Lenten fasting. The gift of the joy of the Resurrection will be enjoyed ‘openly’ only by those who worked honestly, ‘in secret’, steadfastly repelling all thoughts of vainglory and self-satisfaction.

c. Generous alms-giving

The third key to the entry into Great Lent has to do with the fight against another expression of our egotistical, carnal outlook: avarice. The crucified Lord of Glory, Whom we will venerate on Great Friday didn’t simply die naked on the Cross, having allowed others to snatch away His only remaining clothing. He didn’t even have a bit of earth where He could be buried. Through this final, voluntary act of poverty He wishes to cure our absurd greed, which lays up things on earth as treasures, though for the most part they become food for worms or plunder for thieves. Rather, He urges us to practice the excesses of alms-giving, through which we store unsullied treasure in heaven.

In today’s Gospel, Christ ends with a phrase which sums up the three golden keys of Lent. Forgiveness, fasting and alms-giving open the door to Lent and make it a true path to Easter, when and if the treasure of our heart is Christ, Whom we consider to be the priceless treasure of our hearts, to Whom we give our hearts. Without this love for the crucified and risen Christ, without this longing and hunger for the slaughtered Lamb, Who will be presented for us at the Paschal table, all the exercises of the virtues are no more than anthropocentric techniques for self-improvement, isolated from any prospect of the joy of the Cross and Resurrection.

‘Those who have convinced themselves that they are righteous’ (Luke 18, 9) have excluded themselves from Christ’s Resurrection Supper. They’re content with their virtues, their egotistical satisfaction as regards their moral progress. If we want to put on the wedding garment which will allow us to sit at the Table of the Kingdom, we need first of all to strip ourselves not only of our sins but also of all self-sufficiency and self-justification, with which we’re usually burdened as a result of our supposedly ‘moral achievements’.